By Jim Surkamp on June 15, 2011 4502 words

John Brown Seeks Out Martin Delany and They Convene to Form a New Promised Land, Chatham Ontario, Canada, May 8, 1858

From:

Rollin, Frank (Frances) A. (1868, 1883). “The Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany.” Boston, MA: Lee & Shepard. PP. 83-95. Print.

Rollin, Frank (Frances) A. (1868, 1883). “The Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany.” Internet Archives: Digital Library of Free Books, Movies, Music, and Wayback Machine. 27 Oct. 2009. Web. 1 June 2011.

The Significance:

The significance of this account by an eyewitness and leader at this convention for a provisional government is that the voted objective of the convention was not to overthrow the Union, as was asserted at Brown’s trial, but that: “an independent community be established within and under the government of the United States, but without the state sovereignty of the compact, similar to the Cherokee nation of Indians, or the Mormons . . .”

What remains contradictory is Brown’s insistence that he needs brave men more than money to achieve his objectives, which appears to assume, in April, 1858, violent methods. Since it was discovered in his belongings at the Kennedy Farm after his arrest, it might be that Brown understood the Constitution, as worded, could be used as part of an effective defense in a trial. Of course, it didn’t turn out that way.

Martin Delany told his biographer Frances Rollin, a woman, (pseudonym “Frank”), that he met John Brown when Brown went to Chatham, West Ontario to find recruits and support for leading an insurrection. Delany agreed to chair a convention to hear his wishes. Delany told Rollin that Brown did not spell out his violent intentions, though others present disagreed with Delany’s self-representation.

John Brown ventured to Chatham, West Ontario, knowing it was well populated with escaped, once enslaved, black Americans. He conceived of a plan at that time to create a new terminus for the Underground Railroad and wanted to create a new state made up of ex-slaves. While getting money from leading abolitionists was possible, his real need was to have brave men to fight with him.

Brown was staying with James Madison Bell, a “plasterer/poet,” at his home on King Street in Chatham in 1858.

Delany, who was then practicing medicine and writing in Chatham saw Brown on a street, recognizing him. When asked, Brown replied: “I am, sir, and I have come to Chatham expressly to see you, this being my third visit on the errand. I must see you at once, sir, and that, too in private, as I have much to do, and but little time before me. If I am to do nothing here, I want to know it at once.”

NOTE: Frequent uses of the pronoun “he” in the following text sometimes can mean either Brown or Delany. The editor adds clarifying notes.

Rollin, Frank (Frances) A. (1868,1883). “The Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany.” Chapter IX, P. 83

“CHAPTER IX. CANADA. – CAPTAIN JOHN BROWN.

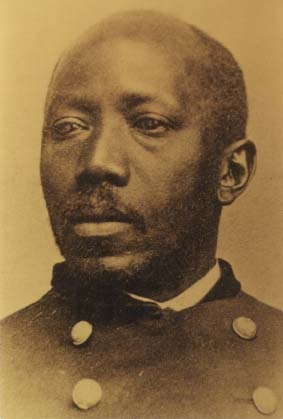

“In February, 1856, he (Delany-ED) removed to Chatham, Kent County, Canada, where he continued the practice of medicine. While his ‘visiting list’ gave evidence of a respectable practice, his fees were not in proportion to it. His practice embraced a great portion of those who were refugees from American slavery; hence his income here did not exceed that acquired at Pittsburg. Here his activity found wider scope, and new fields of labor were opened to him. It was not likely that he of such marked character would remain unrecognized. He was ever suggesting measures tending to ameliorate the condition of one class or another, which resulted in gaining for him an influence only surpassed by that wielded by him at his post of duty at the South. (refers to Delany’s position with the Freedman’s Bureau as a Major in the U.S. Army after the Civil War in South Carolina-ED)

“Once, while in Canada, an important suggestion of his being adopted, it resulted in driving both candidates — conservative and reformer — together, compelling them to offer terms for the support of the black constituency. He took part freely in all political movements in his adopted home. For several years he was one of the principal canvassers in the hustings in the ridings of Kent for the election, and was one of the executive committee, and belonged to the private caucus of A. McKellers, Esq., member of the Provincial Parliament from Kent County. These facts will render it conclusive that his activity was none the less in a country where the progress of his race met no resistance, but only varied in its method. Whatever prominence here, as elsewhere, was attained by him, was cast in the balance as an offering to his people.

“Here were matured his plans for an organization for scientific purposes, which after wards gave him fame in other lands. Here also was he connected with the beginning of a movement in behalf of human liberty, the most sublime in conception, and mysterious in its accomplishment, written of in modern times. The first was in 1858, when had been completed a long contemplated design of his: that of inaugurating a party of scientific men of color to make explorations in certain portions of Africa. In the early part of May, 1859, there sailed from New York, in the bark ‘Mendi,’ owned by three colored African merchants, the first colored explorers from the United States, known as the Niger Valley Exploring Party, at the head of which was its projector, Dr. Delany. His observations he published on his return to this country, so that they need no repetition here, though an important treaty formed with the king and principal chiefs of Abeokuta we have noticed in another portion of this work. It was the importance attached to this mission, and the successful accomplishment of it, that gave him prestige, rendering him eligible to membership of the renowned International Statistical Congress of July, 1860, at London. He traveled extensively in Africa for one year.

“She described him (Brown) as having a long, white beard, very gray hair, a sad but placid countenance”

“In April, prior to his departure for Africa, while making final completions for his tour, on returning home from a professional visit in the country, Mrs. Delany informed him that an old gentleman had called to see him during his absence. She described him as having a long, white beard, very gray hair, a sad but placid countenance; in speech he was peculiarly solemn; she added, ‘He looked like one of the old prophets. He would neither come in nor leave his name, but promised to be back in two weeks’ time.’ Unable to obtain any information concerning his mysterious visitor, the circumstance would have probably been forgotten, had not the visitor returned at the appointed time; and not finding him at home a second time, he left a message to the effect that he would call ‘again in four days, and must see him then.’ This time the interest in the visitor was heightened, and his call was eagerly awaited. At the expiration of that time, while on the street, he recognized his visitor, by his wife’s description, approaching him, accompanied by another gentleman; on the latter introducing him to the former, he exclaimed, ‘Not Captain John Brown, of Ossawatomie?!‘ not thinking of the grand old hero as being east of Kansas, especially in Canada, as the papers had been giving such contradictory accounts of him during the winter and spring. ‘I am, sir,’ was the reply;

I have come to Chatham expressly to see you

“‘this being my third visit on the errand. I must see you at once, sir,’ he continued, with emphasis, ‘and that, too, in private, as I have much to do and but little time before me. If I am to do nothing here, I want to know it at once.’

“’Going directly to the private parlor of a hotel near by,’ says Major Delany, ‘he at once revealed to me that he desired to carry out a great project in his scheme of Kansas emigration, which, to be successful, must be aided and countenanced by the influence of a general convention or council. That he was unable to effect in the United States, but had been advised by distinguished friends of his and mine, that, if he could but see me, his object could be attained at once. On my expressing astonishment at the conclusion to which my friends and himself had arrived, with a nervous impatience, he exclaimed, ‘Why should you be surprised?

‘Sir, the people of the Northern States are cowards; slavery has made cowards of them all. The whites are afraid of each other, and the blacks are afraid of the whites. You can effect nothing among such people,’ he added, with decided emphasis.

“On assuring him if a council were all that was desired, he could readily obtain it, he (Brown-ED) replied, ‘That is all; but that is a great deal to me. It is men I want, and not money; money I can get plentiful enough, but no men. Money can come without being seen, but men are afraid of identification with me, though they favor my measures. They are cowards, sir ! Cowards!’ he reiterated. He then fully revealed his designs. With these I found no fault, but fully favored and aided in getting up the convention.

“(Delany being quoted directly-ED) ’The convention, when assembled, consisted of Captain John Brown, his son Owen, eleven or twelve of his Kansas followers, all young white men, enthusiastic and able, and probably sixty or seventy colored men, whom I brought together.’ His plans were made known to them as soon as he was satisfied that the assemblage could be confided in which conclusion he was not long in finding, for with few exceptions the whole of these were fugitive slaves, refugees in her Britannic majesty’s dominion. His scheme was nothing more than this: To make Kansas, instead of Canada, the terminus of the Underground Railroad; instead of passing off the slave to Canada, to send him to Kansas, and there test, on the soil of the United States territory, whether or not the right to freedom would be maintained where no municipal Power had authorized.

“’He (Brown-ED) stated that he had originated a fortification so simple, that twenty men, without the aid of teams or ordnance, could build one in a day that would defy all the artillery that could be brought to bear against it. How it was constructed he would not reveal, and none knew it except his great confidential officer, Kagi (the secretary of war in his contemplated, provisional government), a young lawyer of marked talents and

singular demeanor.’

“Major Delany stated that he had proposed, as a cover to the change in the scheme, as Canada had always been known as the terminus of the Underground Railroad, and pursuit of the fugitive was made in that direction, to call it the Subterranean Pass Way, where the initials would stand S. P. W., to note the direction in which he had gone when not sent to Canada.

“’He (Delany-ED) further stated that the idea of Harper’s Ferry was never mentioned, or even hinted in that convention. Had such been intimated, it is doubtful of its being favorably regarded. Kansas, where he had battled so valiantly for freedom, seemed the proper place for his vantage-ground, and the kind and condition of men for whom he had fought, the men with whom to fight. Hence the favor which the scheme met of making Kansas the terminus of the Subterranean Pass Way, and there fortifying with these fugitives against the Border slaveholders, for personal liberty, with which they had no right to interfere. Thus it is clearly explained that it was no design against the Union, as the slave-holders and their satraps interpreted the movement, and by this means would anticipate their designs. This also explains the existence of the Constitution for a civil government found in the carpet-bag among the effects of Captain Brown, after his capture in Virginia, so inexplicable to the slaveholders, and which proved such a nightmare to Governor Wise, and caused him, as well as many wiser than himself to construe it as a contemplated overthrow of the Union. The Constitution for a provisional government owes its origin to these facts.

“It was proposed that an independent community be established within and under the government of the United States, but without the state sovereignty of the compact, similar to the Cherokee nation of Indians, or the Mormons . . .

“Major Delany says, ‘The whole matter had been well-considered, and at first a state government had been proposed, and in accordance a constitution prepared. This was presented to the convention; and here a difficulty presented itself to the minds of some present, that according to American jurisprudence, negroes, having no rights respected by white men, consequently could have no right to petition, and none to sovereignty. Therefore it would be mere mockery to set up a claim as a fundamental right, which in itself was null and void. To obviate this, and avoid the charge against them as lawless and unorganized, existing without government, it was proposed that an independent community be established within and under the government of the United States, but without the state sovereignty of the compact, similar to the Cherokee nation of Indians, or the Mormons. To these last named, references were made, as parallel cases, at the time. The necessary changes and modification were made in the Constitution, and with such it was printed. Captain Brown returned after a week’s absence, with a printed copy of the corrected instrument, which, perhaps, was the copy found by Governor Wise.’”

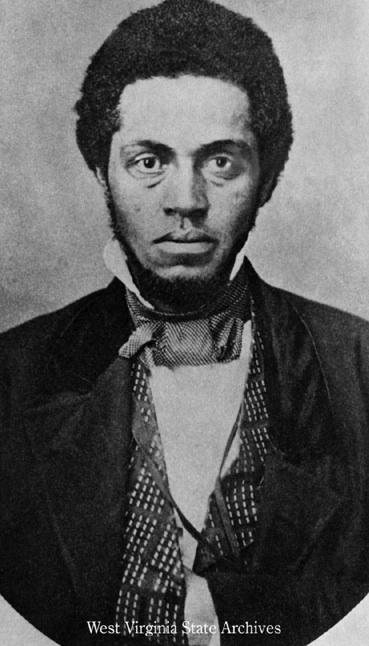

“During the time this grand old reformer of our time was preparing his plans, he often sought Major Delany, desirous of his personal cooperation in carrying forward his work. This was not possible for him (Delany-ED) to do, as his attention and time were directed entirely to the African Exploration movement, which was planned prior to his meeting Captain Brown, as before stated. But as Captain Brown desired that he should give encouragement to the plan, he consented, and became president of the permanent organization of the Subterranean Pass Way, with Mr. Isaac D. Shadd, editor of the Provincial Freeman, as secretary. This organization was an extensive body, holding the same relation to his movements as a state or national executive committee hold to its party principles, directing their adherence to fundamental principles. This, he says, was the plan and purpose of the Canada Convention. Whatever changed them to Harper’s Ferry was known only to Captain Brown, and perhaps to Kagi, who had the honor of being deeper in his confidence than any one else. Mr. Osborn Anderson, one of the survivors of that immortal band, and whose statement as one of the principal actors in that historical drama cannot be ignored, states that none of the men knew that Harper’s Ferry was the point of attack until the order was given to march.

“It was Mr. Anderson whom Captain Brown delegated to receive the sword from Colonel Washington, on that night when the Rubicon of slavery was crossed by that band of hero pioneers who confronted the slave power in its strong-hold. The first sound of John Brown’s rifle, reverberating along the Shenandoah, proclaimed the birth of Freedom. Already he saw the mighty host he invoked in Freedom’s name. He heard their coming footfalls echoing over Virginia’s hills and plains, and upon every breeze that swept her valleys was borne to him his name entwined in battle anthem. He saw in the gathering strife that either Freedom or her priest must perish, and with a giant’s strength he went forward to his high and holy martyrdom, thereby inaugurating victory. FOOTNOTE by Rollin: This sword was a relic of the revolutionary war, presented by Frederick the Great to General Washington, and was kept in the Washington family until that time.”

“CHAPTER X. CANADA CONVENTION. – HARPER’S FERRY.

“It seems remarkable that the man whom Providence had chosen to warn a guilty nation of its danger, and through whom the African race in America received the boon of freedom, which is but a prelude to the entire abolition of slavery on the western continent, should be sent first to Major Delany in Canada, through whom alone he considered himself able to perfect the plans necessary to begin the great work! Certainly the ways of Providence are beyond mortal comprehension.

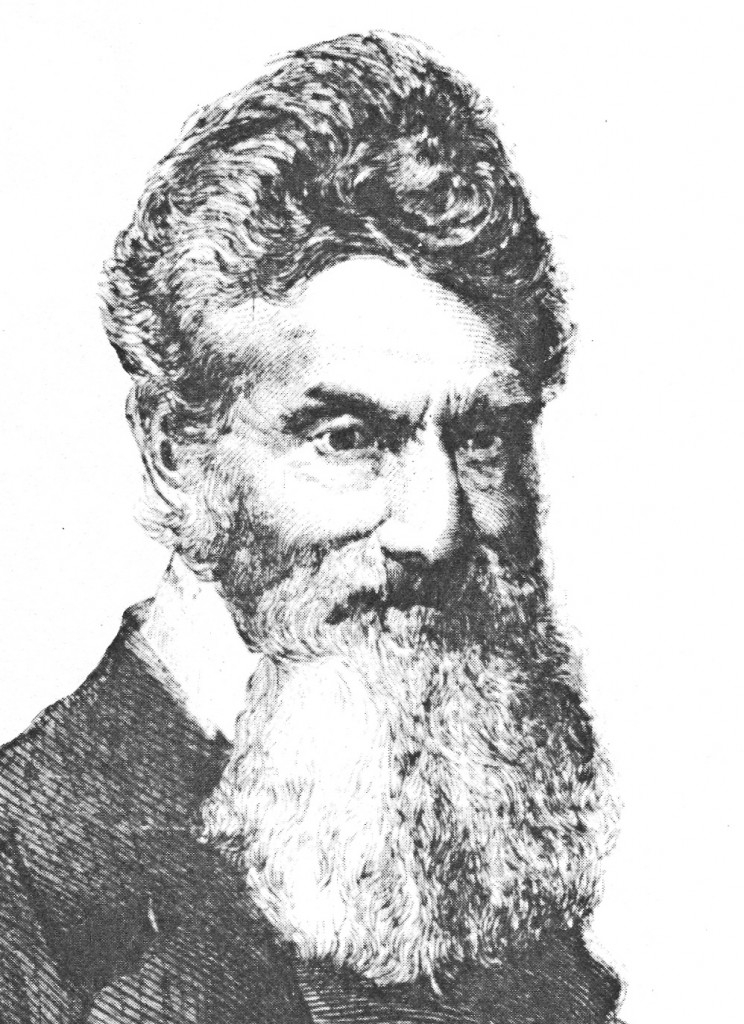

“The extraordinary kindness of the jailer (Photo of John Avis-ED) to the old hero prophet in the midst of hostile men in Virginia elicited surprise in the North, and was the subject of remark by many. To a playfellow of Martin Delany in childhood it was no matter of wonderment that he should sympathize with his helpless, way-worn prisoner, if the heart of the man were at all akin to the heart of the child. The open admiration demonstrated by the Virginia jailer for the character of his captive was a picture striking and pleasing in the midst of all the dark surroundings of that time. The man who, in the midst of hostile faces lowering with hate and fear towards him who sat beside him on his way to death, could say, ‘Captain Brown, you are a game man,’ proved himself, after his prisoner, the bravest man in Virginia that day.

“ In regard to the relation sustained by the brave Avis to Major Delany in childhood, it may be of interest to know that the acquaintance was renewed in after years, during the Mexican war, by the major’s frequently sending him copies of the paper of which he was then editor in Pittsburg. These were duly acknowledged by Captain Avis, who recognized his name, and adverted to some of the scenes of their childhood, but cautioned him against sending them regularly, lest it should attract attention at the post-office, the paper being thoroughly anti-slavery, and taking grounds against the war, as being waged for the propagation of slavery. Hence anti-slavery sentiments were not unfamiliar to Avis. And we know not but that at some time, in that lonely prison cell, the name of Martin Delany,

“whom the testimony of Mr. Richard Realf before the Senate committee had made to play such a conspicuous part in the singularly significant councils at Chatham, was mentioned; and who can say it may not have been a link that had first knit the captor to the captive?

“The testimony of Mr. Realf before the Senate committee appointed to investigate the Harper’s Ferry affair resulted in placing Major Delany in a most cowardly light. The charges were to the effect that he, ‘Dr. Delany, had repeatedly urged the black men in the convention, and that all his acts and advices tended to encourage them to go with Captain Brown, to aid in an overthrow of the government, as a measure that would succeed.’

(Convention was held at the Chatham Baptist Church)

This is without foundation. Major Delany is remembered, by those who attended the Canada Convention councils at Chatham, as having objected to many propositions favored by Captain Brown, as not having the least chance of giving trouble to the slaveholders, except the fortification at Kansas. At one time, having objected repeatedly to certain proposed measures, the old captain sprang suddenly to his feet, and exclaimed severely, ‘Gentlemen, if Dr. Delany is afraid, don’t let him make you all cowards!’

“Dr. Delany replied immediately to this, courteously, yet decidedly. Said he, ‘Captain Brown does not know the man of whom he speaks: there exists no one in whose veins the blood of cowardice courses less freely; and it must not be said, even by John Brown, of Ossawatomie.’ As he concluded, the old man bowed approvingly to him, then arose, and made explanations.

“He accounted for Mr. Realf ‘s discrepancies from the fact that the young man was a stranger to the country, and understood but little of its policy, and his former position in life never brought him in contact with men of such character as

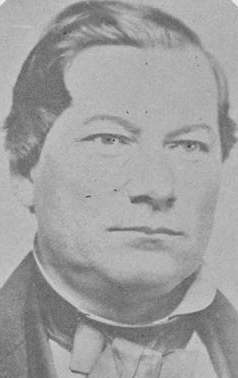

Sen. James Mason, the committee chair

“Mason, of Trent notoriety, and the rest of the pro-slavery committee, upon whose torturing rack he was stretched, upon the charge of attempting to overthrow the government!

“But a few years after beheld the chairman of that committee a fugitive, a prisoner, and an exile, and Virginia the battle-ground of contending armies, one inspired by an anthem commemorating the name of him whom Virginia in her madness sacrificed to her destruction, the other endeavoring to destroy the Union in accordance with the teachings of the judges of Captain Brown and his followers.

“While this stem judge of the Senate Chamber was hiding his blighted name in exile, the name of Richard Realf shone among the brightest at Lookout Mountain, as he rushed forward, amid a shower of bullets, to replace the national standard after its bearer had fallen. These misrepresentations of Major Delany’s connection with the Harper’s Ferry insurrection embarrassed him greatly, at one time, while abroad, which we give, and will also show the importance attached to the Harper’s Ferry invasion abroad.

“While reporting on his explorations during his visit to Scotland, a letter (anonymous) was sent to

Sir Culling Eardley. Eardley, implicating the Major (Dr. Delany) with the ‘insurgents under John Brown.’ Such was the effect of this insidious missive, that a whole day (Sabbath) was spent by gentlemen of the highest social and public position in discussing the matter, and considering the propriety of dropping and denouncing him.

“But wisdom prevailed, and they determined to disregard the anonymous informant’s advice. With this a learned ex-official of her majesty’s government called upon him at his residence in Glasgow, and reported the proceedings to him. He was met with an argument from Major Delany, to which he assented, and replied that it was the same in substance as used by himself and the great-hearted Sir Culling Eardley. After passing through the scrutiny of these British statesmen, he received no further annoyance concerning this while in Europe.

“Of the movement at Harper’s Ferry, followed by the almost immediate execution of Captain Brown and his devoted followers, he was ignorant, until in Abeokuta he received a copy of the New York Tribune sent from England for him. It was after the Canada Convention, in accordance with designs as before stated, he embarked for Africa, accompanied by Robert Douglass, Esq., of Philadelphia, the genius whom prejudice denied the right to study peacefully his glorious art in the academy of his native city, but whom the Royal Academy of England received within its portals, and Professor Robert Campbell, of the Philadelphia Institute for colored youth.”

Main references:

Anderson, Osborne. (1861). “A Voice from Harper’s Ferry: A Narrative of Events at Harper’s Ferry; with Incidents Prior and Subsequent to its Capture by Captain Brown and His Men.” Boston MA: self-published. Print.

Anderson, Osborne. (1861). The Life and Public Services of Martin R. Delany.” Internet Archives: Digital Library of Free Books, Movies, Music, and Wayback Machine. 27 Oct. 2009. Web. 1 June 2011.

Surkamp, James. “To Be More Than Equal: The Many Lives of Martin R. Delany 1812-1885.” West Virginia University Libraries. 9 Nov. 1999. Web. 9 Nov. 1999.

“Chapter 7: Preparing to Take the War Into Africa.” ‘John Brown His Soul Goes Marching On.’ West Virginia Archives and History. 25 July 2008. Web. 10 July 2010.

“Senate Select Committee Report on the Harper’s Ferry Invasion

Testimony of Richard Realf, PP. 90-113.” ‘John Brown His Soul Goes Marching On.’ West Virginia Archives and History. 25 July 2008. Web. 10 July 2010.

“Journal of the Provisional Constitutional Convention, held on Saturday, May 8, 1858.”

‘John Brown His Soul Goes Marching On.’ West Virginia Archives and History. 25 July 2008. Web. 10 July 2010.

Ullman, Victor. (1971). “Martin R. Delany: The Beginnings of Black Nationalism.” Boston, MA: Beacon Press. Print.

Ullman, Victor. (1971). “Martin R. Delany: The Beginnings of Black Nationalism.” Amazon.com 12 Dec. 1998 Web. 1 June 2011.

Videos:

Surkamp, Jim. (2009). “John Brown Raid Descendants Speak at 150th Oct., 2009.” {Video}. (9:41). Retrieved 26 Jan. 2011 from:

Flickr Set:

baptistch.chatham.jpg

“First Baptist Church in Chatham.” Photo. ‘John Brown His Soul Goes Marching On.’ West Virginia Archives and History. 25 July 2008. Web. 10 July 2010.

brown004.jpg

The Library of Congress

delany.jpg

“Martin Robison Delany.” Photo. U. S. Army Heritage & Education Center.

U. S. Army War College, Carlisle, PA.

frwhip.jpg

“Frances R. Whipper” Photo. ‘To Be More Than Equal: The Many Lives of Martin R. Delany 1812-1885.’ West Virginia University Libraries. 9 Nov. 1999. Web. 9 Nov. 1999

jamesmason.jpg

“James M. Mason.” Photo. ‘John Brown His Soul Goes Marching On.’ West Virginia Archives and History. 25 July 2008. Web. 10 July 2010.

johnavis.jpg

“John Avis.” Photo. ‘Kansas Memory’ 17 Oct. 2007. Web. 7 June 2011.

osborneperryanderson.jpg

“Osborne Perry Anderson.” Photo. ‘John Brown His Soul Goes Marching On.’ West Virginia Archives and History. 25 July 2008. Web. 10 July 2010.

richardrealf.jpg

“Richard Realf.” Photo. ‘John Brown His Soul Goes Marching On.’ West Virginia Archives and History. 25 July 2008. Web. 10 July 2010.

cullingeardley.jpg

“Sir Culling Eardley Smith.” ‘University of St. Andrews, Library Photographic Archive.’ 12 Dec. 1997. Web. 7 June 2011.