3376 words

This is an important, first-hand account of Harper’s Ferry events in mid-April, 1861 by (later Brigadier-General, C.S.A.) John D. Imboden. Imboden describes how he roused the Governor from bed to extract promises of support of military action, even before the Secession Convention has made its final vote to secede. He frankly describes encounters with opponents to his actions in his home County of Augusta and elsewhere. One senses what the Imboden group did was close to being an unauthorized seizure of power. The drama of the burning of the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry while Virginia militias are fast approaching is portrayed. He opines that the arsenal’s former superintendent, Alfred Barbour, disclosed their secret plan.

Following Imboden’s account is another memoir of what happened by

Thomas Gold, who came that night with militia from adjacent Clarke County and Berryville, Va. He later was in Co. I of the 2nd Virginia.-ED

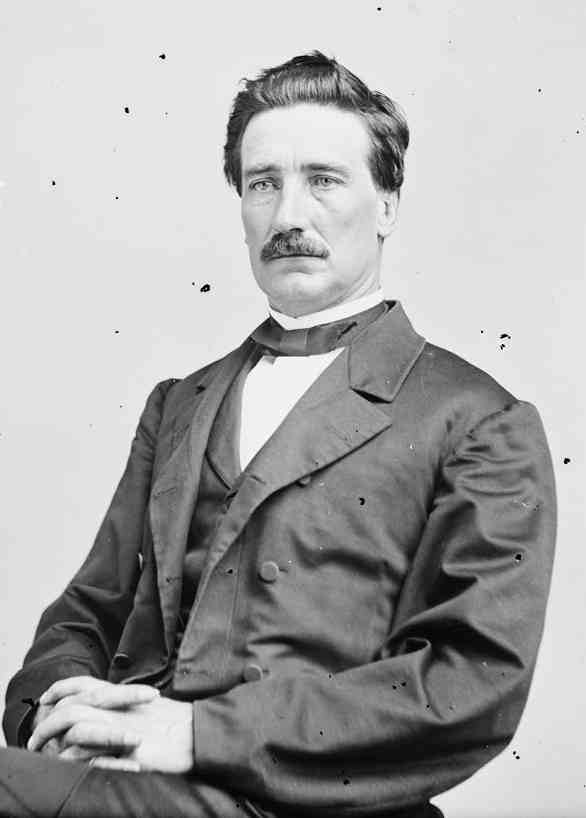

JOHN IMBODEN’S FIRST-HAND STORY:

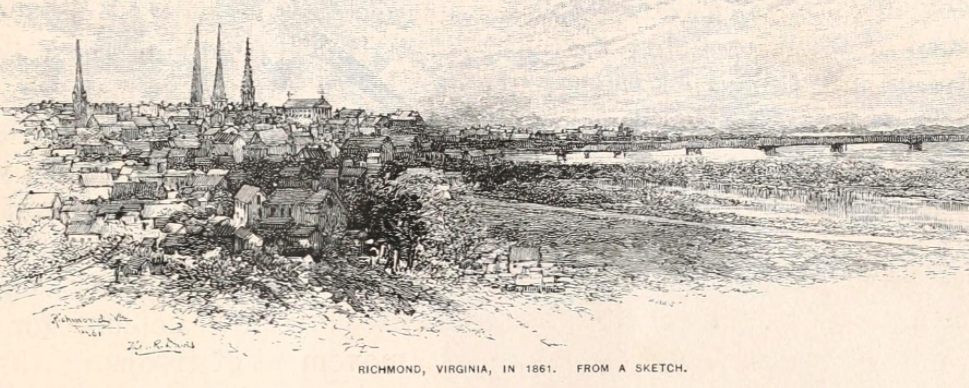

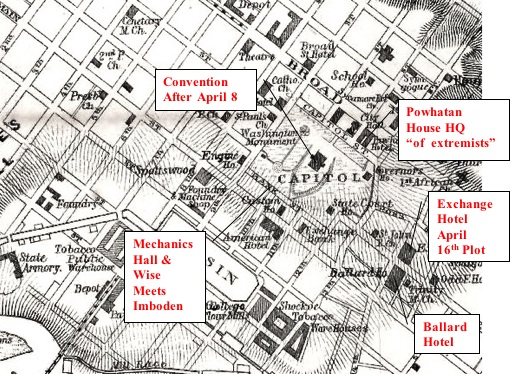

The movement to capture Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, and the fire-arms manufactured and stored there was organized at the Exchange Hotel in Richmond on the night of April 16th, 1861.

Ex-Governor Henry A. Wise was at the head of this purely impromptu affair. The Virginia Secession Convention, then sitting, was by a large majority “Union” in its sentiment till Sumter was fired on and captured, and Mr. Lincoln called for seventy-five thousand men to enforce the laws in certain Southern States. Virginia was then, as it were, forced to ‘take sides,’ and she did not hesitate.

I had been one of the candidates for a seat in that convention from Augusta county, but had been overwhelmingly defeated by the “Union” candidates, because I favored secession as the only “peace measure.” Virginia could then adopt, our aim being to put the State in an independent position to negotiate between the United States and the seceded Gulf and Cotton States for a new Union, to be formed on a compromise of the slavery question by a convention to be held for that purpose.

Late on April 15th I received a telegram from ‘Nat’ Tyler, the editor of the ‘Richmond Enquirer,’ summoning me to Richmond, where I arrived the next day. Before reaching the Exchange Hotel I met ex-Governor Wise on the street. He asked me to find as many officers of the armed and equipped volunteers of the inland towns and counties as I could, and request them to be at the hotel by 7 in the evening to confer about a military movement which he deemed important. Not many such officers were in town, but I found Captains Turner Ashby and Richard Ashby of Fauquier county, Oliver R. Funsten of Clarke county, all commanders of volunteer companies of cavalry; also Captain John A. Harman of Staunton my home and Alfred M. Barbour, the latter ex-civil superintendent of the Government works at Harper’s Ferry. These persons, with myself, promptly joined ex-Governor Wise, and a plan for the capture of Harper’s Ferry was at once discussed and settled upon. The movement, it was agreed, should commence the next day, the 17th, as soon as the convention voted to secede, provided we could get railway transportation and the concurrence of Governor Letcher. Colonel Edmund Fontaine, president of the Virginia Central railroad, and John S. Barbour, president of the Orange and Alexandria and Manassas Gap railroads, were sent for, and joined us at the hotel near midnight. They agreed to put the necessary trains in readiness next day to obey any request of Governor Letcher for the movement of troops.

A committee, of which I was chairman, waited on Governor Letcher after midnight, and, arousing him from his bed, laid the scheme before him. He stated that he would take no step till officially informed that the ordinance of secession was passed by the convention. He was then asked if contingent upon the event he would next day order the movement by telegraph. He consented.

We then informed him what companies would be under arms ready to move at a moment’s notice. All the persons I have named above are now dead, except John S. Barbour, ‘Nat’ Tyler, and myself. On returning to the hotel and reporting Governor Letcher’s promise, it was decided to telegraph the captains of companies along the railroads mentioned to be ready next day for orders from the governor. In that way I ordered the Staunton Artillery, which I commanded, to assemble at their armory by 4 PM on the 17th to receive orders from the governor to aid in the capture of the Portsmouth Navy Yard. This destination had been indicated in all our dispatches, to deceive the Government at Washington in case there should be a “leak” in the telegraph offices. Early in the evening a message had been received by ex-Governor Wise from his son-in-law Doctor Garnett of Washington, to the effect that a Massachusetts regiment, one thousand strong, had been ordered to Harper’s Ferry. Without this reinforcement we knew the guard there consisted of only forty-five men, who could be captured or driven away, perhaps without firing a shot, if we could reach the place secretly. The Ashbys, Funsten, Harman, and I remained up the entire night. The superintendent and commandant of the Virginia Armory at Richmond, Captain Charles Dimmock, a Northern man by birth and a West Point graduate, was in full sympathy with us, and that night filled our requisitions for ammunition and moved it to the railway station before sunrise. He also granted one hundred stand of arms for the Martinsburg Light Infantry, a new company just formed. All these I receipted for and saw placed on the train.

Just before we moved out of the depot, Alfred Barbour made an unguarded remark in the car, which was overheard by a Northern traveler, who immediately wrote a message to President Lincoln and paid a negro a dollar to take it to the telegraph office. This act was discovered by one of our party, who induced a friend to follow the negro and take the dispatch from him. This perhaps prevented troops being sent to head us off. My telegram to the Staunton Artillery produced wild excitement, and spread rapidly through the county, and brought thousands of people to Staunton during the day. Augusta had been a strong Union county, and a doubt was raised by some whether I was acting under the orders of Governor Letcher. To satisfy them, my brother, George W. Imboden, sent a message to me at Gordonsville, inquiring under whose authority I had acted. On the arrival of the train at Gordonsville, Captain Harman received the message and replied to it in my name, that I was acting by order of the governor. Harman had been of the committee, the night before, that waited on Governor Letcher, and he assumed that by that hour noon the convention must have voted the State out of the Union, and that the governor had kept his promise to send orders by wire. Before we reached Staunton, Harman handed me the dispatch and told me what he had done. I was annoyed by his action till the train drew up at Staunton, where thousands of people were assembled, and my artillery company and the West Augusta Guards (the finest infantry company in the valley) were in line.

Major-General Kenton Harper, a native of Pennsylvania, “a born soldier” and Brigadier-General William H. Harman, both holding commissions in the Virginia militia, and both of whom had won their spurs in the regiment the State had sent to the Mexican war, met me as I alighted, with a telegram from Governor Letcher ordering them into service, and referring them to me for information as to our destination and troops.

Until I imparted to them confidentially what had occurred the night before, they thought, as did all the people assembled, that we were bound for the Portsmouth Navy Yard. For prudential reasons, we said nothing to dispel this illusion. The governor in his dispatch informed General Harper that he was to take chief command, and that full written instructions would reach him en route. He waited till after dark, and then set out for Winchester behind a good team. Brigadier- General Harman was ordered to take command of the trains and of all troops that might report en route.

About sunset we took train; our departure was an exciting and affecting scene. During the night, the Monticello Guards, Captain W. B. Mallory, and the Albemarle Rifles, under Captain R. T. W. Duke, came aboard. At Culpeper, a rifle company joined us, and just as the sun rose on the 18th we reached Manassas. The Ashbys and Funsten had gone on the day before to collect cavalry companies, and also the famous “Black Horse Cavalry,” a superb body of men and horses, under Captains John Scott and Welby Carter of Fauquier. By marching across the Blue Ridge, they were to rendezvous near Harper’s Ferry.

Ashby had sent men on the night of the 17th to cut the wires between Manassas Junction and Alexandria, and to keep them cut for several days. Our advent at the Junction astounded the quiet people of the village. General Harman at once “impressed” the Manassas Gap train to take the lead, and switched two or three other trains to that line in order to proceed to Strasburg. I was put in command of the foremost train.

We had not gone five miles when I discovered that the engineer could not be trusted. He let his fire go down, and came to a dead standstill on a slight ascending grade. A cocked pistol induced him to fire up and go ahead. From there to Strasburg I rode in the engine-cab, and we made full forty miles an hour with the aid of good dry wood and a navy revolver. At Strasburg we left the cars, and before 10 o’clock the infantry companies took up the line of march for Winchester. I now had to procure horses for my guns.

The farmers were in their corn-fields, and some of them agreed to hire us horses as far as Winchester, eighteen miles, while others refused. The situation being urgent, we took the horses by force, under threats of being indicted by the next grand jury of the county. By noon we had a sufficient number of teams. We followed the infantry down the Valley Turnpike, reaching Winchester just at nightfall.

The people generally received us very coldly. The war spirit that bore them up through four years of trial and privation had not yet been aroused. General Harper was at Winchester, and had sent forward his infantry by rail to Charlestown, eight miles from Harper’s Ferry. In a short time a train returned for my battery. The farmers got their horses and went home rejoicing, and we set out for our destination.

The infantry moved out of Charlestown about midnight. We kept to our train as far as Halltown, only four miles from the ferry. There we set down our guns to be run forward by hand to Bolivar Heights, west of the town, from which we could shell the place if necessary.

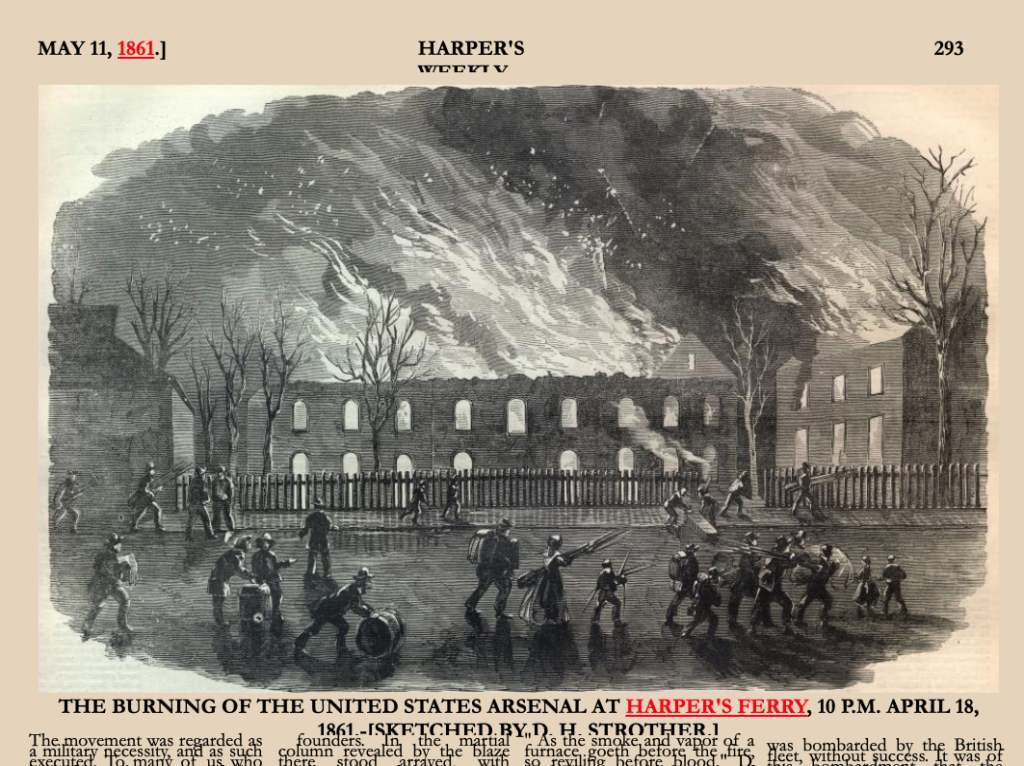

A little before dawn of the next day, April 18th, a brilliant light arose from near the point of confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers. General Harper, who up to that moment had expected a conflict with the Massachusetts regiment supposed to be at Harper’s Ferry, was making his dispositions for an attack at daybreak, when this light convinced him that the enemy had fired the arsenal and fled. He marched in and took possession, but too late to extinguish the flames.

Nearly twenty thousand rifles and pistols were destroyed. The workshops had not been fired. The people of the town told us the catastrophe, for such it was to us, was owing to declarations made the day before by the ex-superintendent, Alfred Barbour. He reached Harper’s Ferry, via Washington, on the 17th about noon, and, collecting the mechanics in groups, informed them that the place would be captured within twenty-four hours by Virginia troops. He urged them to protect the property, and join the Southern cause, promising, if war ensued, that the place would be held by the South, and that they would be continued at work on high wages. His influence with the men was great, and most of them decided to accept his advice. But Lieutenant Roger Jones, who commanded the little guard of forty-five men, hearing what was going on, at once took measures to destroy the place if necessary.

But Lieutenant Roger Jones, who commanded the little guard of forty-five men, hearing what was going on, at once took measures to destroy the place if necessary.

Trains of gunpowder were laid through the buildings to be fired. In the shops the men of Southern sympathies managed to wet the powder in many places during the night, rendering it harmless. Jones’s troops, however, held the arsenal buildings and stores, and when their commander was advised of Harper’s rapid approach the gunpowder was fired, and he crossed into Maryland with his handful of men. So we secured only the machinery and the gun and pistol barrels and locks, which, however, were sent to Richmond and Columbia, South Carolina, and were worked over into excellent arms.

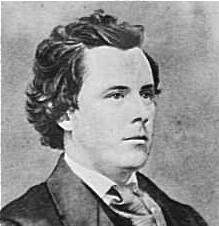

Remembered by Thomas D. Gold:

Gold, Thomas D. (1914). “History of Clarke County, Virginia.” Berryville, VA: C. R. Hughes Publishers. Print.

Gold, Thomas D. (1914). “History of Clarke County, Virginia.” Internet Archives: Digital Library of Free Books, Movies, Music, and Wayback Machine. 27 Oct. 2009. Web. 28 Dec. 2010.

What was feared suddenly happened. Mr. Lincoln ordered out 75,000 troops and called on Virginia for her quota. Immediately the sentiment of all changed, and the convention determined to cast the fortunes of the old Commonwealth with her sister Southern states. Upon this being determined, orders were issued for the volunteer companies of the State to meet and prepare for the struggle.

On the morning of the 17th of April, 1861, Captain Bowen received orders to march with his company to Harper’s Ferry to aid in its capture. At Harper’s Ferry were the U. S. Armory and Arsenal, where were stored large quantities of arms and ammunition, very important for us to have. Messengers were sent hurrying through the county, ordering the members of the company to report in uniform and with arms at Berryville by 12 m. of that day, but with singular want of foresight no orders for rations were issued even for the one day. The men gathered promptly, and by 1 o’clock were ready for the march. There were hasty goodbyes, many tears by anxious mothers and wives over sons and husbands departing for no one could guess what fate. But among the men, especially the young and thoughtless, all was joy and hilarity. No idea of the terrible events which were so soon to follow. No idea of the long years of toil and danger entered into their minds. We would soon settle matters and be at home again. We were carried in four-horse wagons furnished by the farmers of the neighborhood, and from the top of what is now Cemetery Hill, we took our departure. On reaching Charlestown we found that the 2nd Regiment, under Col. J. W. Allen, composed of the companies from Jefferson County, had marched to Halltown, four miles from Harper’s Ferry. We pushed on, arriving there about sundown, as did also the Nelson Rifles, a company from Millwood under command of Capt. W. N. Nelson. After a supper of crackers and cheese and very fat middling, we started on the march.

About two miles from the Ferry we were halted, and for the first time heard the command, afterward to be so familiar, ‘load at will.’ That sounded like business. Intense excitement ensued. Some in their hurry loaded with the ball end of the cartridge foremost, others tore off the powder and left only the ball, all of which gave trouble later. One fellow became deadly sick and had to retire.

Fortunately just then a young man of the county who had followed, came up and there in the road they exchanged clothing, the sick man going back home, never to be of any account again. Fear so possessed him that he never rallied, and eventually left the service. But our excitement and flurry amounted to nothing. We marched into the Ferry, meeting no one. The U. S. troops there, a company of infantry, after setting fire to the armory, had crossed the bridge and marched to Chambersburg. We arrived on the scene in time to see the burning buildings and no more. We had quarters in the Catholic Church, and during the night arrested a number of citizens, attempting to secure guns stolen from the armory. On the next day we entered upon the real life of a soldier, never to be relaxed until that fateful day at Appomattox when, our toils, labors and sacrifices over, we laid down the arms so sanguinely taken up. Officers and men soon found that they had all to learn as to war and its affairs. No one knew how to make a cake of bread or cook a piece of meat, and only one man in the company could make a cup of coffee. I well remember with what curiosity we gathered around Bob Whittington to see him make coffee. At first for a few days we were in a Battallion of the two companies from Clarke under command of Capt. Wm. N. Nelson of Millwood, but soon we were placed in Colonel Allen’s regiment, which for a while was called the 1st Virginia.

The old 1st Virginia was formed from Richmond companies and claimed the right to retain their number, which the government conceded to them, although we were the first to organize in the field. We never envied them their name or reputation, as we felt that we were as well drilled, although not as well uniformed, and that we did as good service and we are sure that the 2nd Virginia earned by hard service and gallant fighting as good a name as they.

Useful Local Links:

“Did Virginia Commit Treason?” – Dennis Frye

The Red Dawn of Sedition – David Hunter Strother

References:

Gold, Thomas D. (1914). “History of Clarke County, Virginia.” Berryville, VA: C. R. Hughes Publishers. Print.

Gold, Thomas D. (1914). “Jackson at Harpers Ferry in 1861.” Internet Archives: Digital Library of Free Books, Movies, Music, and Wayback Machine. 27 Oct. 2009. Web. 26 Sept. 2010.

This is an important, first-hand account of Harper’s Ferry events in mid-April, 1861 by (later Brigadier-General, C.S.A.) John D. Imboden. Imboden describes how he roused the Governor from bed to extract promises of support of military action, even before the Secession Convention has made its final vote to secede. He frankly describes encounters with opponents to his actions in his home County of Augusta and elsewhere. One senses what the Imboden group did was close to being an unauthorized seizure of power. The drama of the burning of the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry while Virginia militias are fast approaching is portrayed. He opines that the arsenal’s former superintendent, Alfred Barbour, disclosed their secret plan.

Following Imboden’s account is another memoir of what happened by

Thomas Gold, who came that night with militia from adjacent Clarke County and Berryville, Va. He later was in Co. I of the 2nd Virginia.-ED