5163 words

CHAPTER or STORY 9 – THE SOBER FACTS, BUT GEORGE JOHNSON “GETS CLEAR” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4LJpJeIwFMw#t=25m06s

FLICKR 58 images

https://www.flickr.com/photos/jimsurkamp/albums/72157688724464186

With support from American Public University System (apus.edu). The sentiments expressed do not in any way reflect modern-day policies of APUS, and are intended to encourage fact-based exchange for a better understanding of our nation’s foundational values.

Click Here and it will take you to the start of this story within the much longer story and video. START: 25:06 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4LJpJeIwFMw#t=25m06s

THE DARKER SIDE SOME SAW:

But others in Jefferson County, like the enslaved George Johnson saw the darker side of slavery and and struck out for his freedom and Life.

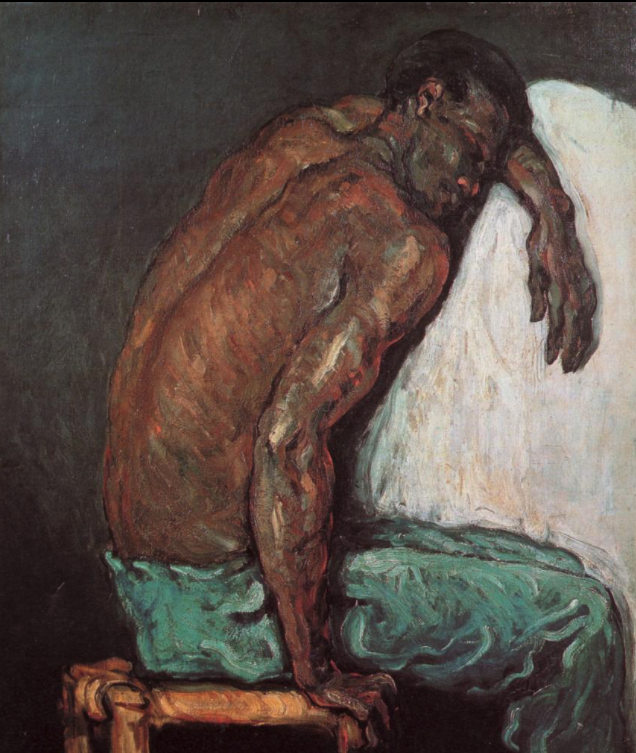

Records show that in the darker recesses of Jefferson County, cruelties were quietly administered by some.

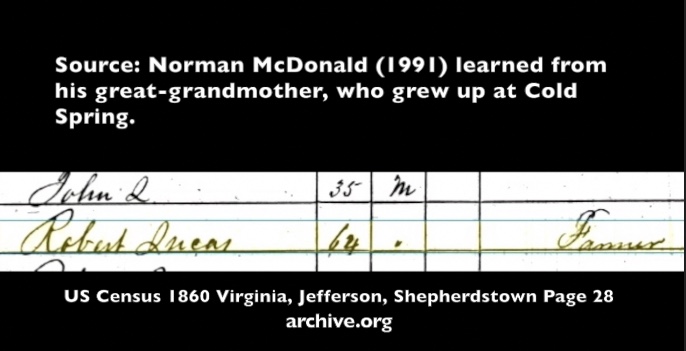

Col Robert Lucas having a horse stampeded, thereby dragging a returned runaway to his death whose foot was tied to the horse.

Or the old man at the poor farm on Leetown Road in the 1930s with but one hand, the other cut off by a half-mad overseer who thought it worthy punishment for – “lying.”

Or Bertha Fox Jones’ recorded account of her ancestor, Mary Fox at the Bower who was last seen being whipped in an open wagon that drove away for refusing to be a brood woman.

George Johnson who was raised in Harper’s Ferry and later escaped and established a home in Chatham, Ontario, wrote:

“I was raised near Harper’s Ferry. I was used as well as the people about there are used.

Home page of David Hunter Strother drawings at West Virginia University Library

web.archive.org

“My master used to pray in his family with the house servants, morning and evening. I attended these services until I was eighteen, when I was put out on the farm, and lived in a cabin.

commons.wikimedia.org

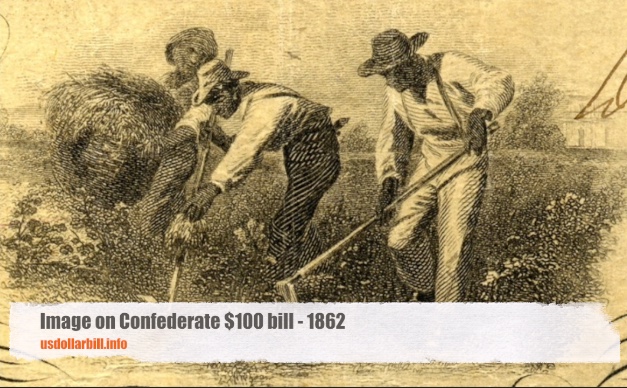

“We were well supplied with food. We went to work at sunrise, and quit work between sundown and dark. Some were sold from my master’s farm, and many from the neighborhood. If a man did any thing out of the way, he was in more danger of being sold than of being whipped. The slaves were always afraid of being sold South. The Southern masters were believed to be much worse than those about us. I had a great wish for liberty when I was a boy. I always had it in my head to clear.”

He went on:

“Whipping and slashing are bad enough, but selling children from their mothers and husbands from their wives is worse. At one time I wanted to marry a young woman, not on the same farm. I was then sent to Alabama, to one of my masters’ sons for two years. When the girl died, I was sent for to come back. I liked the work, the tending of cotton, better than the work on the farm in Virginia,–but there was so much whipping in Alabama, that I was glad to get back.”

References:

GEORGE JOHNSON – pp. 52-54.

I arrived in St. Catharine’s about two hours ago.

[April 17, 1855]

I was raised near Harper’s Ferry. I was used as well as the people about there are used. My master used to pray in his family with the house servants, morning and evening. I attended these services until I was eighteen, when I was put out on the farm, and lived in a cabin. We were well supplied with food. We went to work at sunrise, and quit work between sundown and dark. Some were sold from my master’s farm, and many from the neighborhood. If a man did any thing out of the way, he was in more danger of being sold than of being whipped. The slaves were always afraid of being sold South. The Southern masters were believed to be much worse than those about us. I had a great wish for liberty when I was a boy. I always had it in my head to clear. But I had a wife and children. However, my wife died last year of cholera, and then I determined not to remain in that country.

When my old master died, I fell to his son. I had no difficulty with him, but was influenced merely by a love of liberty. I felt disagreeably about leaving my friends, — but I knew I might have to leave them by going South. There was a fellow-servant of mine named Thomas. My master gave him a letter one day, to carry to a soul-driver. Thomas got a man to read it, who told him he was sold. Thomas then got a free man to carry the letter. They handcuffed , the free man, and put him in jail. Thomas, when he saw them take the free man, dodged into the bush. He came to us. We made up a purse, and sent him on his way. Next day, the man who had carried the letter, sent for his friends and got out. The master denied to us that he intended to sell Thomas. He did not get the money for him. Thomas afterward wrote a letter from Toronto to his friend.

I prepared myself by getting cakes, etc., and on a Saturday night in March, I and two comrades started off together. They were younger than I. We traveled by night and slept by day until we reached Pittsburgh. When we had got through the town, I left the two boys, and told them not to leave while I went back to a grocery for food. When I returned, they were gone, — I do not know their fate. I stopped in that neighborhood two nights, trying to find them — I did not dare to inquire for them. The second night, I made up my mind to ask after them, but my heart failed me. I am of opinion that they got to Canada, as they knew the route. At length I was obliged to come off without them.

I think that slavery is not the best condition for the the refugee; or a black. Whipping and slashing are bad enough, but selling children from their mothers and husbands from their wives is worse. At one time I wanted to marry a young woman, not on the same farm. I was then sent to Alabama, to one of my master’s sons for two years. “When the girl died, I was sent for to come back. I liked the work, the tending of cotton, better than the work on the farm in Virginia, — but there was so much whipping in Alabama, that I was glad to get back. One man there, on another farm, was tied up and received five hundred and fifty lashes for striking the overseer. His back was awfully cut up. His wife took care of him. Two months after, I saw him lying on his face, unable to turn over or help himself. The master seemed ashamed of this, and told the man that if he got well, he might go where he liked. My master told me he said so, and the man told me so himself. Whether he ever got well, I do not know: the time when I saw him, was just before I went back to Virginia.

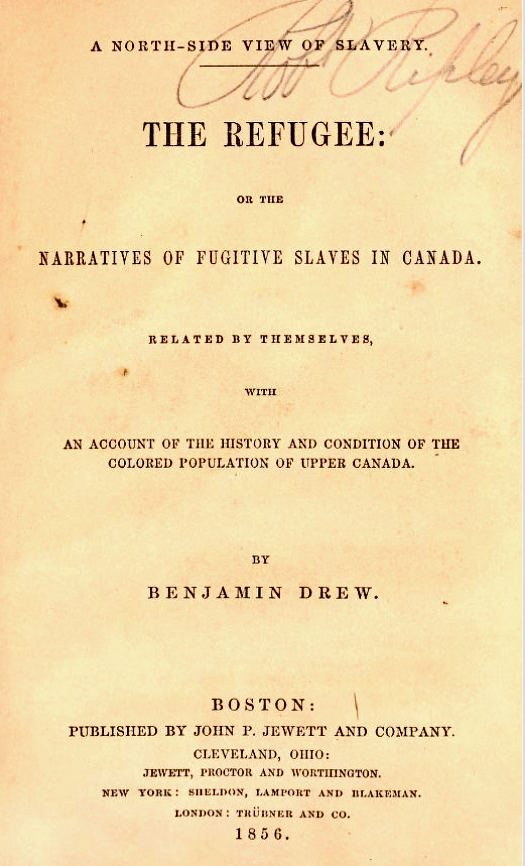

Drew Benjamin. (1856). “A North-side View of Slavery: The Refugee: Or, The Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada …” archive.org

pp. 52-54 – George Johnson’s account

https://archive.org/details/northsideviewofs00drew/page/52/mode/2up

Other escape accounts from Benjamin Drew’s book of interviews with persons from Jefferson County

WILLIAM GROSE: pp. 82-87

I was held as a slave at Harper’s Ferry, Va. When I was twenty-five years old, my two brothers who were twelve miles out, were sent for to the ferry, so as to catch us all three together, which they did. We were then taken to Baltimore to be sold down south. The reason was, that I had a free wife in Virginia, and they were afraid we would get away through her means. My wife and two children were then keeping boarders; I was well used, and we were doing well. All at once, on Sunday morning, a man came to my house before I was up, and called me to go to his store to help put up some goods. My wife suspected it was a trap: but I started to go. When I came in sight of him, my heart failed me; I sent him word I could not come.

On inquiry in a certain quarter, I was told that I was sold, and was advised to make my escape into Pennsylvania. (83) I then went to my owner’s, twelve miles, and remained there three days, they telling me I was not sold. The two brothers were all this time in jail, but I did not then know it. I was sent to the mill to get some offal— then two men came in, grabbed me and handcuffed me, and took me off. How I felt that day I cannot tell. I had never been more than twenty miles from home, and now I was taken away from my mother and wife and children. About four miles from the mill, I met my wife in the road coming to bring me some clean clothes. She met me as I was on horseback, handcuffed. She thought I was on the farm, and was surprised to see me. They let me get down to walk and talk with her until we came to the jail: then they put me in, and kept her outside. She had then eight miles to go on foot, to get clothes ready for me to take along. I was so crazy, I don’t know what my wife said. I was beside myself to think of going south. I was as afraid of traders as I would be of a bear. This was Tuesday.

The man who had bought us came early Wednesday morning, but the jailer would not let us out, he hoping to make a bargain with somebody else, and induce our owners to withdraw the bond from the man that had us. Upon this, the trader and jailer got into a quarrel, and the trader produced a pistol, which the jailer and his brother took away from him. After some time, the jailer let us out. We were handcuffed together: I was in the middle, a hand of each brother fastened to mine.

We walked thus to Harper’s Ferry: there my wife met me with some clothes. She said but little; she was in grief and crying. The two men with us told her they would get us a good home. We went by the cars to (84) the Baltimore — remained fifteen days in jail. Then we were separated, myself and one brother going to New Orleans, and the other remained in B. Him I have not seen since, but have heard that he was taken to Georgia. There were about seventy of us, men, women, and children shipped to New Orleans. Nothing especial occurred except on one occasion, when, after some thick weather, the ship came near an English island, the captain then hurried us all below and closed the hatches. After passing the island, we had liberty to come up again.

We waited on our owners awhile in New Orleans, and after four months, my brother and I were sold together as house servants in the city, to an old widower, who would not have a white face about him. He had a colored woman for a wife — she being a slave. He had had several wives whom he had set free when he got tired of them. This woman came for us to the yard, — then we went before him. He sent for a woman, who came in, and said he to me, ” That is your wife. I was scared half to death, for I had one wife whom I liked, and didn’t want another, — but I said nothing. He assigned one to my brother in the same way. There was no ceremony about it — he said ” Cynthia is your wife, and Ellen is John’s.” As we were not acclimated, he sent us into Alabama to a watering-place, where we remained three months till late in the fall — then we went back to him. I was hired out one month in a gambling saloon, where I had two meals a day and slept on a table ; then for nine months to an American family, where I got along very well; then to a man who had been mate of a steamboat, and whom I could not please.

After I (85) had been in New Orleans a year, my wife came on and was employed in the same place, (in the American family). One oppression there was, my wife did not dare let it be known she was from Virginia, through fear of being sold. When my master found out that I had a free-woman for a wife there, he was angry about it, and began to grumble. Then she went to a lawyer to get a certificate by which she could remain there. He would get one for a hundred dollars, which was more than she was able to pay: so she did not get the certificate, but promised to take one by-and-by. His hoping to get the money kept him from troubling her, — and before the time came for her taking it, she left for a distant place. He was mad about it, and told me that if she ever came there again, he’d put her to so much trouble that she would wish she had paid the hundred dollars and got the certificate. This did not disturb me, as I knew she would not come back any more.

After my wife was gone, I felt very uneasy. At length, I picked up spunk, and said I would start. All this time, I dreamed on nights that I was getting clear. This put the notion into my head to start — a dream that I had reached a free soil and was perfectly safe. Sometimes I felt as if I would get clear, and again as if I would not. I had many doubts. I said to myself — I recollect it well, — I can’t die but once ; if they catch me, they can but kill me: I’ll defend myself as far as I can. I armed myself with an old razor, and made a start alone, telling no one, not even my brother. All the way along, I felt a dread — a heavy load on me all the way. I would look up at the telegraph wire, and dread that the news was going on ahead of me. At one time I was on a canal-boat — it did not seem to go (86) fast enough for me, and I felt very much cast down about it ; at last I came to a place where the telegraph wire was broken, and I felt as if the heavy load was rolled off me, I intended to stay in my native country,— but I saw so many mean-looking men, that I did not dare to stay. I found a friend who helped me on the way to Canada, which I reached in 1851.

I served twenty-five years in slavery, and about five I have been free. I feel now like a man, while before I felt more as though I were but a brute. When in the United States, if a white man spoke to me, I would feel frightened, whether I were in the right or wrong; but now it is quite a different thing, — if a white man speaks to me, I can look him right in the eyes — if he were to insult me, I could give him an answer. I have the rights and privileges of any other man. I am now living with my wife and children, and doing very well. When I lie down at night, I do not feel afraid of over-sleeping, so that my employer might jump on me if he pleased. I am a true British subject, and I have a vote every year as much as any other man. I often used to wonder in the United States, when I saw carriages going round for voters, why they never asked me to vote. But I have since found out the reason, — I know they were using my vote instead of my using it — now I use it myself. Now I feel like a man, and I wish to God that all my fellow-creatures could feel the same freedom that I feel. I am not prejudiced against all the white race in the United States, — it is only the portion that sustain the cursed laws of slavery.

Here ‘s something I want to say to the colored people in the United States: You think you are free there, but you are very much mistaken: if you wish to be free men, I hope you will all come to Canada as soon (87) as possible. There is plenty of land here, and schools to educate your children. I have no education myself, but I don’t intend to let my children come up as I did. I have but two, and instead of making servants out of them, I’ll give them a good education, which I could not do in the southern portion of the United States. True, they were not slaves there, but I could not have given them any education.

I have been through both Upper and Lower Canada, and I have found the colored people keeping stores, farming, etc., and doing well. I have made more money since I came here, than I made in the United States. I know several colored people who have become wealthy by industry — owning horses and carriages, — one who was a fellow-servant of mine, now owns two span of horses, and two as fine carriages as there are on the bank. As a general thing, the colored people are more sober and industrious than in the States: there they feel when they have money, that they cannot make what use they would like of it, they are so kept down, so looked down upon. Here they have something to do with their money, and put it to a good purpose.

I am employed in the Clifton House, at the Falls.

Drew, pp. 82-87.

https://archive.org/details/northsideviewofs00drew/page/82/mode/2up

Adams, Julia D. (1990). “Between the Shenandoah and the Potomac: Historic Homes of Jefferson County, West Virginia.” Charles Town, West Virginia: The Jefferson County Historical Society, p. 121.

Recorded interviews with Bertha Fox Jones and Norman McDonald https://justjefferson.com/16Day.htm

Robert Lucas entry

US Census 1860 Virginia Jefferson Shepherdstown Page 28 – fold3.com

https://www.fold3.com/image/75222890/?terms=robert%20Lucas

Julia S. Blickenstaff; Carmen Creamer; Don Wood; Beverley Grove; Galtjo Geertsema (December 13, 1994) “National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Jefferson County Alms House” (pdf). National Park Service.

CHAPTER OR STORY 10 CLICK HERE https://civilwarscholars.com/uncategorized/chapter-10-jasper-begins-his-life-1844-by-jim-surkamp/