We drive our cars to Charles Town driving from the direction of the Casino towards town.

At the first light in town (Washington Street intersecting Mildred Street), you turn RIGHT onto Mildred Street, go one block, turn LEFT on to Liberty Street. Drive just past the rear of the Presbyterian Church on your left to the entrance into a parking lot shared by the church and the next structure – the Charles Town Library. Turn in there, park and go up the steps and walk to your right 1.5 blocks to the Jefferson County courthouse.

In 1803, the first courthouse was built upon this site. While we have not discovered a detailed description of this courthouse, an 1830 plat of Charles Town shows it as a two-story structure, without columns, but with a tower. It was probably in the Federal style, and must have been rather modest, as it was paid for from contributions and not from taxes. The county grew so quickly that, in 1836, the first courthouse was pulled down to make way for a larger one. The plan had been to sell the courthouse and build in another location. However, it was discovered that, if not used for a courthouse, the property would revert to the Washington family. The new courthouse was constructed as a Doric temple in the Greek revival style. Although there have been some changes, this is the courthouse that still stands. In 1836, the ground floor was one big courtroom. This courtroom had windows in all four walls and was heated by large iron stoves. The judge and court officials sat on an elevated platform, behind a railing with turned balusters. https://www.jeffersoncountywv.org/about-jefferson-county/courthouse-history

Judge Sanders continues giving the history of the courthouse in his essay:

On October 16, 1859, John Brown led a band of 21 men against the Federal Arsenal and Armory at Harper’s Ferry. They killed five and wounded nine in the raid. Ten of the conspirators were killed, five escaped, and six were arrested by troops under Col. Robert E. Lee.

The raiders were taken to Charles Town for trial. The charges were: murder, inciting slaves to rebel, and treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. The trial began Wednesday October 26, and concluded Monday October 31, 1859. It took only one day to hear all the witnesses. The jury was out only half an hour before a verdict of guilty on all counts was returned.

After Brown’s trial and conviction, he was taken to the jail, located diagonally across George Street, where the present post office stands. Brown remained in jail through November while his conviction was appealed. On the 2nd of December 1859, Brown was taken from the jail. He rode in a wagon, seated atop his coffin, to a field a short distance away. The site is along present-day Samuel Street, between Hunter and Mason Streets. There, surrounded by troops and VMI cadets, he was hanged. It was 35 minutes before his pulse ceased. Brown was 59. After the execution, Brown’s body was taken to Harper’s Ferry and turned over to his wife.

VIDEO of the 150th re-enactment of the hanging of John Brown, organized by Job Crops (whose students built the gallows “to spec” and County employee, Kirk Davis, organized a cavalry contingent) drew well-known actors of the John Brown family. Comedian/activist Dick Gregory was also present, along with descendants of John Brown and John A. Copeland. TRT: 7:01 Video link: https://youtu.be/K1jnnRPuM-E

On October 18 1863, troops and artillery under Confederate General John D. Imboden surrounded Union troops in the courthouse. The brief battle that ensued damaged the courthouse. After that, the courthouse was used as a stable. By war’s end the metal roof had been removed and made into bullets.

When West Virginia was formed in 1863, Jefferson County had remained a part of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Shortly after, a highly questionable “election” abducted Jefferson County into the new state. By war’s end, the county seat was moved to Shepherdstown.

In 1872, the county seat was returned to Charles Town, and the damaged courthouse was restored. The walls and columns were made higher and a broad cornice, or entablature, was added below the roofline. Above the portico, the belltower was enlarged to include a town clock. Walls were added to the first floor interior, creating offices and supporting the floor above. A grand, new courtroom with a 25 ft. ceiling was created on the second floor. It features a balcony, referred to as the “ladies listening gallery”. The new courtroom was heated by stoves, and after a few years, was lit by a large “soil kerosene” chandelier. Like the courtroom of 1836, it had windows with wooden shutters all around. Also, like the 1836 courtroom, railings and balusters defined the bench and the well of the court. A single painting hangs in the courtroom – a portrait of Andrew Hunter, a lawyer of Charles Town, who served as special prosecutor in John Brown’s Trial. This new courtroom was home to the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals from 1873 until 1912. During these forty years, the Supreme Court would ride circuit. It sat one term a year in Charles Town, one term in Charleston, and one term in Wheeling.

In 1910, an annex was constructed onto the rear of the courthouse for judge’s chambers, jury and witness rooms, and a clerk’s office. In 1919, the old jail was sold to the post office and a new one was built behind the courthouse.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85059533/1913-11-29/ed-1/seq-3/#date1=1777&index=10&rows=20&words=E+Graham+Wilson&searchType=basic&sequence=0&state=&date2=1963&proxtext=E.+Graham+Wilson&y=0&x=0&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1

In 1913, the second of the three most famous trials in the courthouse resulted in the conviction of E. Graham Wilson for the sexual assault of Katie Turner, whose composure and acuity during hours of tough grilling by defense attorneys and support from a doctor and minister won wide praise from news outlets. Wilson was sentenced to fourteen years in prison. But failing health led to his highly questionable pardon by West Virginia Governor Hatfield after only three years.

In 1922, 250 miles from Charles Town in the southwestern coalfields of West Virginia, enraged miners inflamed by Mother Jones and union leaders, attempted to invade and unionize Logan County. The “Battle of Blair Mountain” resulted. Actual warfare, with machine guns and aerial bombardment followed. Two thousand Federal troops were needed to stop the fighting. A special Logan County grand jury was convened. Returned were 738 indictments charging treason and murder.

Miners’ trial, group outside Jefferson County Court House, circa 1922. (IMG1390) John League

https://jeffcomuseumwv.org/virtual_exhibit/vex1/images/7577c31a-1d58-43cd-8311-357590663202.jpg

The venue was transferred to Jefferson County. Again, Charles Town was the site for a set of high profile treason trials. The national and world media descended on the town. The newly formed State Police were present in such number that it seemed like martial law. John L. Lewis, Governor Ephraim F Morgan and other notables were in attendance.

In the first trial, union leader Bill Blizzard was acquitted of treason.

After that, a Reverend Wilburn and his son were convicted of 2nd degree murder. The governor later commuted their sentences. Next, Walter Allen was convicted of treason against the State. He was released on bond pending appeal and remanded at large. After those trials, venue was moved to Morgan, then Greenbrier, then Fayette County. However, no other trials were ever held, and the remaining indictments were dismissed.

Today, the Jefferson County Courthouse remains a working courthouse, not a museum. It stands at the vital center of government in this busy county. Combining architectural and historical significance, it is an eloquent monument to democracy. https://www.jeffersoncountywv.org/about-jefferson-county/courthouse-history

Videos by Jim Surkamp on the Jefferson County courthouse:

The Lively Odyssey of the “John Brown” Courthouse by Jim Surkamp September 17, 2014 TRT: 15:31 https://youtu.be/_zMNnuFOivE NOTE: The video states incorrectly that the deed books were removed at the outset of the war when, in fact, Clerk Thomas A. Moore ceased entering new entries in November, 1862, suggesting that was when he removed the deed books and other records to Lexington.

The VERY historic John Brown & Miner’s Trial Courthouse – Charles Town, WV by Jim Surkamp June 8, 2018 TRT: 5:34 https://youtu.be/J582xLTfM1w

From the videos:

The Courthouse during the Civil War (from the videos)

Record creator War Department. Office of the Chief Signal Officer. (08/01/1866 – 09/18/1947) Title Col. David H. Strother Date: between circa 1860 and circa 1865. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Hunter_Strother

Martinsburg-born and Union officer David Hunter Strother wrote in his diary in the spring of 1862 of the near disastrous fire in Charles Town set by Union soldiers – and put out by Union soldiers under his command along with the townspeople. (NOTE: He mentions “standing guard outside Mrs. Hunter’s home” She was his deeply Confederate mother-in-law. Also “Redmonds” is the hotel across the street from the courthouse – today the Bank of Charles Town offices):

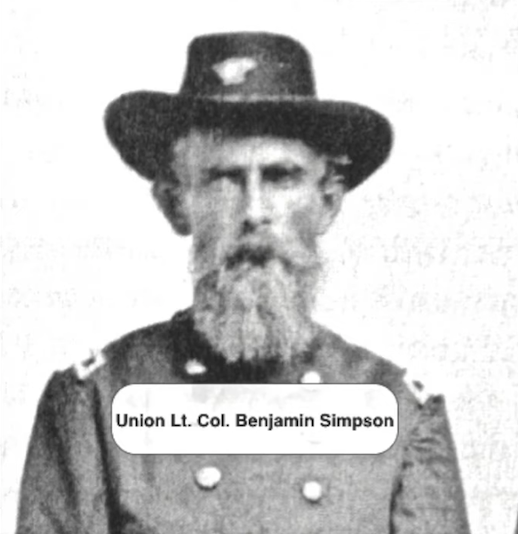

On October 18th 1863, Confederate General John Imboden surprised a Union garrison commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Simpson within Charlestown’s courthouse. Simpson wrote later: “I went out and saw approaching on horseback with a flag of truce in his hand. ‘Halt what do you want?'”

“General Imboden demands the unconditional surrender of the town.” Said Simpson: ‘If he wants to, tell him to come and take it.” In about five minutes the gentlemen came back: “General Imboden requests that you remove all the women and children from the houses in the vicinity of the courthouse and jail as he intends to shell the town. (Simpson) This shall be done, but it will take about an hour.”

(Imboden messenger): “You must think we are foolish.” A shell struck one corner of the courthouse and glancing from against the log palisade exploded. Every shot they fired struck the courthouse. A third shot entered it and exploding in the palisade of the upper story wounded the adjutant and one private. There were from 10 to 20 shells that struck and exploded in the courthouse and around it.

Sunday August 21st 1864, James E. Taylor, an artist with general Sheridan’s army wrote: “We passed to the courthouse to view the 6th and 8th corps after their arduous work and holding Early in check on the Smithfield Pike. “It would require an inspired pen to truly picture the intensified emotion and gloomy silence that pervaded the ranks of the musketeers as they moved by the old temple of Justice in the growing night –

all in marked contrast to their elastic steps on a bright morning a few days earlier when with waving banner the martial music and voices that inspired the song “John Brown’s body is a harbinger of victory.”

Having about an hour to learn at the Courthouse, we go inside and I show you key documents, such as John Brown’s death notice and Jane Charlotte Washington’s will leaving Mount Vernon to her son and a few more. We take in the John Brown Trial and exhibit in the hallway. We discuss, seated in the last surviving portion of the original John Brown courtroom that has been replaced mostly by office cubicles, etc.

We go outside again and turn towards the steps to street level on George Street. We bring you the extraordinary lives of six people, one you know well:

Charles Broadway Rouss was born in 1836 in Maryland and his life, ending in 1902, encompassed losing two, maybe three, fortunes, and making another final fortune worth six million dollars upon his death. He had a great generosity with a habit of picking men up from the gutter and building them back to success. He wrote phonetically (shown in the video)in his syndicated column. One must have “luk” and “pluk” to prosper. When he became blind at the peak of his success, he offered a million dollars to anyone who could find a cure. He wanted business or “biznes” to serve humanity. July, 2020 TRT: 23:22

www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-nmUJ5A4wE&t=78s – Flickr files – https://www.flickr.com/photos/jimsurkamp/51024183847/in/album-72157718601716392/ – The Unstoppable Charles Broadway Rouss Part 2 (with bibliography) – by Jim Surkamp August, 2020 TRT: 18:43 https://youtu.be/DF1k-e9cdqg

https://www.pafa.org/museum/collection/item/john-brown-going-his-hanging

After the war, the handicapped Pippin devised a way of supporting his right hand with his left. Using a hot poker to burn in the outlines of his figures and objects onto wood (a technique called pyrography) and then filling them in, he was able to resume painting by the mid-1920s. He then began using oil paints. Local exhibitions and collectors brought him to the attention of Alain Locke, an important black philosopher and critic, the painter N.C. Wyeth,… and Dr. Albert F. Barnes, whose private museum in Merion houses one of the world’s most important collections of French impressionist and modern art. . . In his obituary in the New York Times they called him the “most important Negro painter” to have appeared in America.”

https://gwarlingo.com/2013/horace-pippin/

Getting close to 10 AM, we walk in the direction of our cars, but instead, walk and turn left on to Samuel Street and turn right into the Jefferson County Museum that is full of relics from history of national and even international importance. Ms. Lori Wysong is the new director

John Brown Raid Descendants Speak at 150th Oct., 2009 at the County Museum by Jim Surkamp – The great, great, great grand-daughter of John Brown, and the great great great grand-niece of John Copeland and another descendant of John Brown talk about their ancestors who were hanged in Charles Town, Va (now WV) in 1859 following the John Brown Raid on Harpers Ferry at Charles Town during the 150th anniversary of the John Brown Raid in 1859. TRT: 9:41 Video link: https://youtu.be/sSsx1Ebz5Qw

John Brown “Hanging” 2009 by Jim Surkamp Oct., 2009

A solemn observance of John Brown at his gallows, horses, wagon, comment, trumpet solo in recognition of the 150th anniversary of his hanging December 2nd in 1859 in Charles Town. TRT: 7:01 Video link: https://youtu.be/K1jnnRPuM-E

VIDEO: Harriet Lane America’s Original First Lady by Jim Surkamp February, 2020

CORRECTION at 1:06:28 The images of Harriet’s sons are reversed: sitting is James Buchanan Johnston, standing is Henry Elliot Johnston Jr. TRT: 1:09:35

Video link: https://youtu.be/r0NBsXgs6fI

VIDEO: Harriet Lane’s Star Rises Over Incredible London 1854-1855 by Jim Surkamp February, 2020 – A chapter in a sixty-six minute, factual video/story about how Harriet Lane, the niece, but declared “consort” (by Queen Victoria) to her Uncle James Buchanan, the Ambassador from the U.S. in London. During that brief period Harriet saw world events from every side: the Crimean War, a doctor’s discovery of the cause of cholera while five hundred died in two months in the city, Charles Dickens’ latest book called “High Times,” and a re-opening of the fabled Crystal Palace – the scene of the first World’s Fair in 1851. And the gifted, unique 25-year old Harriet deftly absorbed all these heady influences (except cholera!). She was prepared during her Uncle’s and (bachelor) term as President from 1857-1861 to become one of the most admired and beloved First Ladies ever at the age of twenty-seven, and was called the original “First Lady” in 1860 by Frank Leslie’s illustrated newspaper. Her many uncles and cousins considered Jefferson County, Virginia home. TRT: 25:57 Video link: https://youtu.be/SF_6xodgzHs

VIDEO: How Queen Victoria protected the U.S. from Ruin by Jim Surkamp February, 2020 This is a segment of a sixty-six minute long video about the remarkable life of Harriet Lane Johnston often called the Original First Lady. TRT: 23:23 Video link: https://youtu.be/AGYg4ecOnLE

The Queen Helps (“Saves”?) the U.S. May 13, 1861

https://civilwarscholars.com/uncategorized/the-queen-helps-the-u-s-may-13-1861/

Harriet L. B. Johnson – Conclusion by Jim Surkamp

https://civilwarscholars.com/uncategorized/harriet-l-b-johnson-conclusion/

VIDEO: John Peale Bishop of Charles Town – Inspired the young F. Scott Fitzgerald to Write TRT: 5:43 Video link: https://youtu.be/wDlkxb1nkEA

VIDEO: John Peale Bishop Pt. 1 by Jim Surkamp (Originally mid-1990s) December, 2008 TRT: 5:42 Describes the great formative influence that writer John Peale Bishop had on young fellow Princeton undergrad, F. Scott Fitzgerald back in 1913 and how They remained friends for life. John Peale Bishop was from Charles Town and became the editor of Vanity Fair. Video link: https://youtu.be/1JQ4zlAm24o

NEXT Gathering Place – The Carriage Inn up the street two blocks away called “the most Civil-Warred, Still Standing Home”

VIDEO: The Amazing Story of the Carriage Inn by Jim Surkamp (1)

TRT: 7:16 Video link: https://youtu.be/id0xxSjDiwk

VIDEO: The Amazing Carriage Inn of Charles Town (3) – The Feds get “Red” by Jim Surkamp August, 2014 TRT: 15:23 Video link: https://youtu.be/9edEwMKF95k

Next to Last Gathering Place – Zion Episcopal Churchyard two short blocks from The Carriage Inn, featuring the members of the Washington family

From Zion Churchyard we walk back towards George Street to the home of John Peale Bishop where his friend Scott Fitzgerald, currently in the midst of completing “This Side of Paradise” spent a month in this house (July, 1916). It is located at the S. George and East Academy Street Street intersection.

Scott Fitzgerald spent every day of that July with a young women, home from boarding school named “Fluff” Beckwith, who in later wrote this unforgettable remembrance of the not yet famous writer. No wonder he liked her!:

Elizabeth Beckwith MacKie.

My Friend Scott Fitzgerald.

This is to reverse the usual pattern. I am unable to report for boast that during a long friendship with Scott Fitzgerald I ever slept with him. Hardly a month passes but some new, revealing love affair, or indiscretion among the famous, comes out of hiding and into print. And so it is with a proper sense of failure that I cannot add a single flaming episode to tingle the thoughts of that vast hoard who make up Scott’s admirers.

It would not have been easy to sleep with Scott, knowing as I did his ideals about the married state, which, when it could have happened, was the case with both of us. It would have destroyed too much. And yet I am not blind to the idea that it might also have brought added beauty to our relationship. There were times when I knew that he needed me, or the physical love and understanding of a woman, and I have let slip the chance to claim even one page for myself from the love life of one of the greats. The truth is that Scott never came right out — wham — and asked me!

It would be unfair to consider Scott Fitzgerald in any light other than a serious one. It would be a misconception of a man whose approach to life was anything but casual. He was dead serious about life, love, art, and friendship, and especially his dedication to his own talent.

We know he often played the clown. His biographers have recorded many such instances, and I saw it happen more times than it is well to remember. But I never saw Scott laugh. I don’t remember the sound of his laughter. Even when he was clowning — it was to make others laugh. He was too intent on what he was doing.

The contrast in his pattern of behavior was most noticeable, of course, when he was drinking. He was a man unfitted for the role that fate dealt him (or that he dealt himself). His public image was not the real Scott. When he was drunk he wanted to shock people, and his mind turned inevitably to sex. He would become provocative and suggestive in a way that was a complete reversal of that rather prudish and extremely sensitive, sober Scott. I believe that it was an unconscious effort on his part to equal or excel his wife, the more glittering Zelda. But he was also the victim of a tragic historic accident — the accident of Prohibition, when Americans believed that the only honorable protest against a stupid law was to break it.

I wouldn’t have met Scott if it hadn’t been for John Peale Bishop. John’s family lived six houses and some acres away from our house, on the same street in Charles Town. West Virginia. John, who was twenty-five, was older than most of our group. A childhood illness (some said tuberculosis, but I never really knew) had slowed his progress through school, and so he had only been graduated from Princeton in June 1917. Now he was marking time waiting for the commission in the army that would take him off to officers’ training camp.

We knew that John’s Princeton friend, Scott Fitzgerald, was arriving for a visit, and my most cherished memento of that visit is a yellowed sheet of paper on which he wrote out for me the sonnet, “When Vanity Kissed Vanity,” which he later included in This Side of Paradise. On it he wrote “For Fluff Beckwith, the only begetter of this sonnet.”

And so the summer, which at the start seemed as routine as all other summers, was soon, in retrospect, to take on added significance by the arrival of a boy, whose name at the time was unimportant, and which I promptly forgot. Scott’s visit lasted four weeks, and we were together every day.

Scott and John had entered Princeton together as freshmen in the autumn of 1913. Despite John’s being considerably older than most freshmen, and Scott’s having been one of the youngest (he was not quite seventeen), they soon became close friends. John, as everyone knows, was the original “Thomas Parke D’lnvilliers” in This Side of Paradise, and Scott recorded in that novel an amusing account of their first meeting and subsequent friendship.

The contrast between these two personalities makes their friendship all the more interesting and unusual. John lacked Scott’s good looks and exuberance. He was perhaps a head taller than Scott, with natural dignity and reserve. His friends were largely selected from the intellectual. My older sister Eloise, was one of his special friends, and he was often at our house. John was a brilliant scholar and prolific poet. In his book of poems Now With His Love, he describes a Lely portrait that hung in our home.

He was instinctively attracted to the handsome, impulsive younger boy, who so flatteringly admired his talent. What they shared most of all was a common passion for the life of Art. At Princeton they worked together on the editorial staff of The Nassau Literary Magazine, in which they published their undergraduate writings. That eventful summer of 1917 marked the publication of John’s first volume of verse, Green Fruit, most of which had been previously published in the Nassau Lit.

John, like Scott, died too soon. He was fifty-one years old, and as with Scott, his greatest recognition came after death. And so while his literary gift to posterity is limited in quantity, that which he left us is pure beauty. His work becomes more popular each year, and his first full-length novel, Act of Darkness, is now being published in paperback.

Scott slipped quietly into Charles Town one afternoon via the dusty old Valley branch of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad, which, except for a limited number of automobiles, was our only escape to the outside world. I had just returned from boarding school in Washington. Our group consisted of boys and girls in their late teens who were home on vacation from school and college. We had all grown up together, and it was our custom to meet almost every day, sometimes in the afternoon for a swim in the nearby Shenandoah River, or for a cross-country ride.

It was July and moonlight — at a party at our house — that I first met Scott. The clematis vine was in full bloom, and the porch railing sagged deeper each year with the weight of the blossoms. The summer air was sweet. I saw him standing in the half shadow watching the dancers. Night had drained the color from his face and hair, and left him pale, but beautiful. He was twenty years old. It was the face of a poet, without sensuality.

We had been dancing to records of “Oh! Johnny” and “Sweethearts,” when John came over to me and said, ’“Fluff, I want you to meet Scott Fitzgerald.” It was an appropriate setting and his first words were a parallel of any boy and girl affair that later brought him fame. “I’ve been watching you,” he said, “trying to guess your real name. Is it Eleanor?” “No, Elizabeth,” I told him. “Then I was close,” he said. “Eleanor — Elizabeth — you see, both names mean pretty much the same kind of girl.”

It wasn’t until I had known him for several days, and watched him with other people, that I realized that other girls all got the same carefully rehearsed treatment. But this discovery, instead of disillusioning me, merely increased my interest in him. Scott was that rare individual that went out of his way to make each girl feel very special. In a way it was nothing but a “line” — except that most boys’ lines are quickly recognizable for what they are. What made Scott’s different was the mixture of art and sincerity that went into every performance. He really wanted each girl to be pleased and flattered, and to respond to him, and she usually did.

The next thing I knew we were dancing together. The best description of his dancing I can think of is “lively.” He had a sense of rhythm and was easy to follow, but he never attempted any trick steps. He liked to talk while he danced, and he enjoyed having a captive audience. But I liked only to feel the lovely close union of body and music, and I found it difficult to concentrate on what he was saying. But suddenly I was listening. I heard him say, “Townsend said he hoped I would meet you.”

Townsend Martin was a classmate of John’s who had visited him in June. He was a cosmopolite of great charm and elegance, and I was dazzled from the beginning. It was an affair that started and ended within safe range of the bridge table, but he soon cast cold water on my hopes by announcing that he was descended from “a long line of bachelors.” This was a deflating experience for a girl who traditionally thought of “belledom” as the only way of life. A new boy, a new interest, was needed to help restore a drooping ego. Afterwards, in my diary for that night of July 2, I wrote: “I met John’s guest. He is good looking. He asked me for a date. We are going on a picnic tomorrow.”

I remember patting my cheeks with a piece of wet pink crepe paper that next afternoon. My parents disapproved of cheek rouge as “too fast,” and instead of black cotton swimming stockings, I wore my best black silk ones. Chaperones were still de rigeur, and our social life was organized around the rule that there was safety in numbers. We were still passionately innocent. If the picnic lasted into the tempting hours of darkness, a chaperone appeared at dusk and joined the group until we were safely back at home.

Scott showed up in his bathing suit, and I surveyed him discreetly but approvingly. He wasn’t terribly tall, but was strong and well-knit. And he was carrying a book. But what struck me most-was his hat. I had never seen a boy go swimming with a hat. He explained that he burned so badly that he had to keep his skin covered up from the sun. And it was true. If he wasn’t careful he turned a painful scarlet. He was a good swimmer, but out of the water we sat in the shade most of time because of his tender skin.

For those of us who lived near the Shenandoah River and loved it, it wound through our lives as between its own banks. Scott soon learned to share our affection for the river, and its many moods. We knew it by heart: one minute flowing blue and lazy, the next a muddy torrent churned by a sudden mountain thunderstorm. We knew the danger spots, and the holes for diving, and the islands where the snakes were thickest. The hidden inlets — just wide enough for a canoe. The gentle rapids where it was so shallow we could lie on our stomachs, and be tossed from rock to rock. And the soft night sounds, broken by song, and echoes on the water.

When the sun dropped behind the Blue Ridge Mountains, Scott and I would drift downstream in a canoe. But the canoes were small, and too crowded for a chaperone — she sat on the bank. Most of the time I listened while he talked and talked. He loved to say things to you that would shock you, just to get your reaction and explain it so accurately that you felt completely exposed. His conversation was mainly about girls. He was always trying to see how far he could go in arousing your feelings, but it was always with words.

“Fluff, have you ever had any ’purple passages’ in your life?” he asked me. I wasn’t sure what it meant, but it sounded exciting. I always expected the questions to develop a more physical tone. The tingling excitement of a mood, slowly developed, yet surely building toward an exquisite moment. But this was his first exposure to southern girls, who in turn had been exposed to less timid southern boys. The southern boys I knew, despite their verbal lethargy, at least understood what it was all about, and were more aggressive and emotionally satisfying. In 1917, I’m afraid, Scott just wasn’t a very lively male animal.

No photograph I have ever seen of him has captured successfully the remarkable sensitivity of his expression. It was like quicksilver. His eyes, contrary to what others have said, were neither green nor blue, but gray-blue. His hair in the sunlight was shining gold. His mouth was his most revealing feature — stern, with their lips. The upper lip had a slight curve to it, but the lower lip was a stern, straight line. All his Midwestern puritanism was there. He had never lived in that magnetic world of the senses, whose inhabitants communicate by a wordless language of intuitive feelings.

In general, however, Scott’s visit to Charles Town was a small social triumph. He was in demand for all the parties, and seemed to enjoy our unsophisticated small-town amusements — and during that month I never saw him take a drink.

Much activity centered around horses. I had been proudly raised with the knowledge that one of my forebears, Sir Marmaduke Beckwith. had been responsible for introducing the first English race-horses into Virginia. Scott had no such feelings about horses or horseback riding — a fact that the horse under him immediately grasped. Scott was a terrible horseman, but determined to ride at all costs. Once he was given an old nag who habitually bolted for home whenever he passed a certain familiar corner. Scott took a bad spill, but got up dusty and determined, and insisted on climbing back on. We all cheered and admired his courage, but it was clear he would never make a good horseman.

One evening just before he left Charles Town, he told me, “Fluff, I’ve written a poem for you,” and he recited “When Vanity Kissed Vanity.”

I felt chilly when he came to the line “and with her lovers she was dead.” “Do you mean you think I’m going to die?” “No.” he replied, “I mean you’re dead to me because your other lovers have taken you from me.” Later, when Edmund Wilson edited the posthumous volume of pieces called The Crack-Up, he published a letter Fitzgerald had written to him. It included the same sonnet, only this time with the title “To Cecilia.” It was a great disappointment at first. Still, the girl was his cousin, and fourteen years older, and besides Scott had given it two months earlier to me.

August came too soon, and Scott returned to his home in St. Paul, Minnesota. And several weeks later, while I was on a trip to New York, friends introduced me to the young man who would soon afterwards marry me and share my life for the next forty-two years. Paul and I first met in Peacock Alley of the old Waldorf-Astoria, on 34th Street, a romantic encounter that Scott would surely have appreciated.

Looking back over the vista of fifty years to that eventful summer when I first met Scott. I know that he could never have been happy with small-town life. He was in search of wider horizons. He failed to discover the real core of small-town life — or its rewards. Small towns are people — there is little else. A place where one comes close to the pulse of human emotion. We learned early about life and living from some of the most beloved members of the colored race — exciting, intimate things, because we were not ashamed to ask. Their wisdom was earthy and uncluttered, and with the sharp intuition of their race. “That ain’t no way to ketch yessef a man, you got to pleasure him, honey, you got to pleasure a man.” “The apple fails close to the tree.” “The sweetest smell of all ain’t no smell at all.” I could go on and on. In the end we were gentler and wiser.

We were all excited when This Side of Paradise was published in the spring of 1920. John Bishop told me that Scott had said I was his model for Eleanor in the section called “Young Irony.” When I read it I remembered our first meeting and Scott’s having told me that Eleanor and Elizabeth were names that suggested to him the same kind of girl. I saw a vague resemblance to myself in his description of Eleanor’s “green eyes and nondescript hair,” and there were Amory’s and Eleanor’s horseback rides through mountain paths together, and the rural setting which was so obviously inspired by the country around Charles Town. And there was, of course, my poem. But the Eleanor he described only reminded me of how little he really knew me. His Eleanor loved to sit on a haystack in the rain reciting poetry. Forgive me, Scott: if that is the way you wanted it, then you missed the whole idea of what can happen atop a haystack.

It wasn’t until fourteen years later, in the early spring of 1932, that I saw him again. By 1932 it seemed as though Zelda had almost recovered from her 1930 collapse. Then, that winter after her father died, she had a second mental breakdown, and Scott brought her from Alabama to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for treatment. By spring she was well enough to be released from the hospital, but her physician wanted her to remain nearby for observation and therapy.

Scott was staying temporarily in a Baltimore hotel, looking for a house to rent for Zelda and himself and eleven-year-old Scottie. Scott liked the idea of settling in Baltimore, alter having spent the last ten years on and off in Europe. He no longer wanted to go back to St. Paul. On his father’s side, the Fitzgeralds had lived in eastern Maryland for generations, and his father, who had recently died, was buried in the family plot at nearby Rockville. Besides, a number of his old Princeton friends were Baltimoreans.

One of his classmates, ’Bryan Dancy, lived next door to us. Bryan and his wife Ida Lee knew that I had once known Scott. So when they heard he was in Baltimore, they invited my husband and me to have dinner with him. A lot had happened since I had last seen Scott. He was now a celebrity, and he was at the height of his popular career. The Great Gatsby had not only been a highly praised novel, but also a Broadway play and a Hollywood motion picture. Besides, Scott was one of the highest-paid magazine writers of the day; The Saturday Evening Post featured his stories regularly. We had learned vaguely of Zelda and her illness. But most of the details were veiled in mystery, and hardly anyone in Baltimore knew her.

When Paul and I arrived at the Dancys’ for dinner, Scott was standing in the living room. I paused for a moment, puzzled by what I saw. There were two Scotts: the old Scott of memory — the other, very drunk. He had run into a second-string Hollywood movie actress staying at his hotel (she was well-known then, but has since died and long been forgotten), and impetuously decided to bring her. They had tarried in the bar too long. She had said she was lonely and knew no one in Baltimore, and Scott felt sorry for her, and told he; to come along. It was a chaotic evening. Scott had obviously decided to make it so. and to confirm his reputation as an unconventional guest. The more vulnerable we appeared, the sharper the attack, with realistic allusions to feminine curves and their function. It was a rejection of the Scott I had known.

As we got up from dinner he started for the front door. He struck a dramatic pose and said: “I am going home — to satisfy a need — the need for sex.” He disappeared through the door, followed by the actress.

I was not entirely unprepared for this behavior. I had heard occasionally over the years from John Bishop. who had briefed me on many of the Fitzgeralds’ more spectacular exploits in Europe. Compared to the fireworks that flared much of the time around Scott and Zelda, John’s life was stable. In 1930 he had won Scribners’ prize for his story, “Many Thousands Gone.” He and his wife Margaret lived quietly as expatriates in a chateau in France, and were the parents of three sons.

All over America drinking was becoming more and more a social habit. But the rest of us had routine responsibilities, our daily jobs to attend to, and our lives were well-organized. Scott was much more of a free agent. There had been nothing of this routine to restrain him, and by the time he came to Baltimore, he had become incapable of controlling his drinking. It magnified the minor flaws in his personality, and erased the charm and good manners.

When Arthur Mizener came to Baltimore in search of Fitzgerald material for his biography of Scott, I hid. I could not at that time discuss my friendship with Scott without, I feared, hurting him. I preferred the privacy of non-recognition. How times have changed. But in spite of that unfortunate meeting, Scott and I eventually got back to a firmer relationship. No matter how badly he behaved, Scott was always sincerely sorry afterwards and would atone by a charming apology. His manners were still beautiful. Physically, he had changed very little during the last fourteen years. He was such a delightful, sensitive person, that my husband Paul, who was rather correct and strait-laced, recovered from his first impression and took a liking to him.

Apart from the drinking, I recognized the same old Scott, but a more retiring Scott than I had known before. He discouraged social invitations, much to the disappointment of the many Baltimore hostesses who had hoped to enliven their parties with such a well-known personage. Zelda, of course, was too ill most of the time to go out in public, but Scott used her illness as an excuse to dodge social entanglements. And deep, deep down he never forgot to love her.

I had not met Zelda before, and saw her only a few times during her stay in Baltimore. I knew that she had once been very beautiful. John Bishop had written me after her wedding that “she looked like an angel.” Now her shoulders drooped and her skin was pallid, but there was about her still a wistful, feminine charm. One afternoon she dropped by to call, and told me she had been shopping all day for a dress with a hood in back. I remember wondering at the time if this was her way of disguising her slouching posture. Another time she invited Ida Lee Dancy and me to lunch at their home, “La Paix.” She kept us waiting for an hour. And when she finally showed up, rather damp-looking, she told us that she had been in the bathtub — that part of her therapy consisted of taking a long sitz-bath to relax her nerves, with a big thermometer to make sure the water stayed the right temperature. She talked freely about her illness.

Scott often dropped by our house for a casual visit. The visits I remembered with the most pleasure were those when, as he expressed it, he was “on the wagon.” The length of these dry spells varied, but they sometimes lasted a month or more. It was during these visits that he often discussed the literary talents of the writers he had known, and he had interesting comments on many of the movie greats of that day. With his usual generosity toward other authors, he told me that Thomas Wolfe was the most gifted writer of his generation. If we were out, he would leave an amusing note — invariably addressed jointly to my husband and me. He liked to drop in unannounced. But he almost always refused invitations to formal parties — especially when there might be lots of people whom he didn’t know. He lacked the interest to make new acquaintances, and preferred old friends. At one of our cocktail parties to which he came, he was immediately surrounded by a circle of admiring, gushing women. When he finally escaped, he told me, “God, I’m sick of all those teeth grinning at me.”

So although we continued to invite him. we soon grew accustomed to his polite letters of apology. After he failed to show up, we would sometimes find a note tucked in the front screen door, like the following, dated July 1933:

Don’t expect me

I’ve gone fancy

I’m all set

With Bryan Dancy

Scotty’s Windbag

Mitchell’s Berries

Back at midnight

Out with Fairies

My last recollection of Scott is in June, 1936. His current plans were to visit Zelda, who was now convalescing in a private sanitarium in North Carolina, and then go out to Hollywood to write for the motion pictures. As things turned out, he was injured while diving in a pool at a hotel in Asheville, and as a result of his having to be hospitalized, his departure for Hollywood was delayed until the following summer of 1937. At the time of our next-to-last meeting, however, he was planning to leave not only Baltimore but the east coast for good. Scott had come to our house to tell us bis plans, and to say that he was leaving as soon as he could get rid of some furniture stored in the Monumental Warehouse in Baltimore.

Paul and I were then spending our summers in the country, and needed furniture, and so Paul bought from Scott a pair of twin beds and a painted chest of drawers. The next day I went to the warehouse. I remember how depressed I was by most of the things — they all looked as though no one had cared very much for them for a long time. I bought one more piece, a bureau, and so I went to the apartment in the Cambridge Arms, to which he and Scottie had moved temporarily, to give him a check.

It was lunch time, but Scott was still in pajamas and bathrobe. He was entertaining Louis Azrael, a well-known local newspaper columnist. He also had a severe pain in his shoulder, which he had relieved by the home remedy of strapping an electric heating pad to his back, and he was sitting on the floor plugged into the electric current. Always restless, and always the perfect host, he would get up from the floor and wander about with plug and cord clattering behind him. But there was also a wonderful dignity flowing from him that repulsed any sympathy of mine and that gave him a kind of tragic grandeur.

This was my farewell to Scott. I would never again see his handsome face, or hear him say, as he once did, when he was leaving our house and the screen door was safely between us, “Fluff. I’ve never had you, but I believe we always get the things we most want.”

His popularity was beginning to go into temporary decline. Shortly after his death I read an obituary by Margaret Marshall in The Nation, February, 1941. She wrote of Scott: “A man of talent who did not fulfill his early promise — his was a fair-weather talent which was not adequate to the stormy age into which it happened, ironically, to emerge.”

Today Scott Fitzgerald is required reading in many schools and colleges, and my grandchildren come with school assignments, wanting to learn more about him. I show them my original copy of the sonnet, “When Vanity Kissed Vanity” — once so lightly received, and now so dearly treasured — when there is no longer cause for vanity. And one of them asked, “Grandmother, did you really kiss Scott Fitzgerald?”

Heavens! No one ever thought of such things in those days. Well — hardly ever.

From Author: I am indebted to Henry Dan Piper for much help and advice in the preparation of this reminiscence.

Reprinted from the Fitzgerald/Hemingway Annual, 1970, by permission of the publisher. Copyright 1970, by the National Cash Register Company.

This is the end of our tour. We return together to our cars located in the parking lot between the Library/Museum and the Charles Town Presbyterian Church.