Harper’s Ferry – Where Large Scale Manufacturing Got Its Start

by Jim Surkamp on June 14, 2011 2668 words.

June, 1856 Harper’s Ferry, Va.

“Our first visit was to the Armory” – from Mayer, Brantz. (April, 1857). “June Jaunt.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine Vol. 15 pp. 592-612

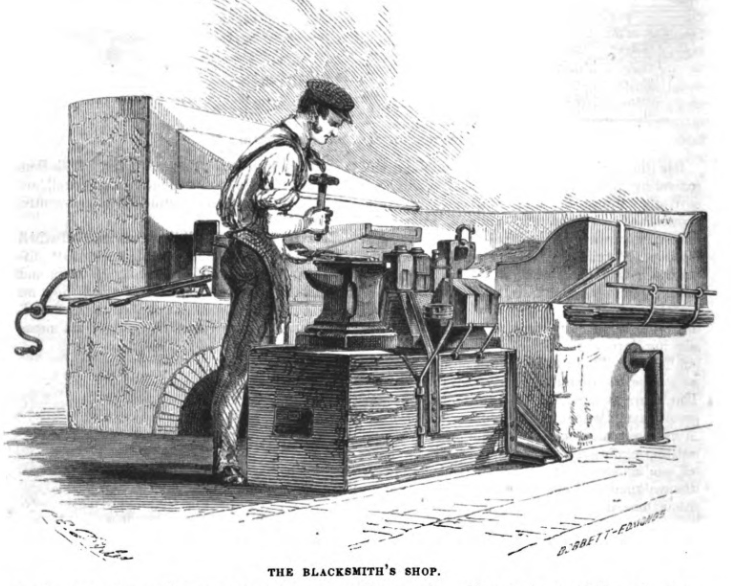

“Our first visit was to the Armory, where we were introduced to all the mysteries in this wonderful assemblage of contrivances for death. Every thing was exhibited and set in motion— from the ponderous tilt-hammers,

“which weld steel into solidity, down to the delicate operations by which the impulse of a hair can put these terrible engines in action. I was soon struck by the fact that, after all, it is not so easy to kill a man—especially, if we consider the intricate preparations which have to be made in constructing weapons for human slaughter.”

“We learned that a musket consists of forty-nine pieces, and that the number of operations in completing one—each of which is separately catalogued and valued—amount to three hundred and forty-six;

all, in some degree, requiring different trades and various capacities for execution; so that, perhaps, no man, or no two men in the establishment, could perform the whole of them in manufacturing a perfect weapon!

“I confess that, with but little turn for mechanical science, most of these complicated machines were rather surprising than comprehensible to me; so that, while my companions strolled through the apartments in quest of instruction, I followed leisurely in their rear, rather grieving than glorying in the inventive skill that had been lavished on their construction under national auspices.”

Brantz Mayer was standing where today’s machine age began in earnest and, where, for the first time succeeded. One author put it: the twin ideas of truly interchangeable parts and using machines more than skilled people to manufacture things merged at Harper’s Ferry just as surely as did.

The idea is to create a process: break its steps of “making” into discrete, measurable, indivisible tasks, arranged in logical sequence. Then create machines to do the primary task, once done by skilled hands. Validation tools and specialized machines maintain the high level of precision, that interchangeability (or interoperability) demands.

The precision then makes parts interchangeable, making mass production and its economies of scale truly possible. Skilled people redirect their skills towards the making of the machines that machine the object.

Even today Microsoft pushed and “sold” interoperability to create a world-wide personal computer-based culture. And writing software is basically the application of these machine concepts to automate ideas for implementation, except the product is distributed as electronic impulses instead of metal or wooden objects.

A software thought-leader wrote in 2001 in a technical paper:

“While challenging to engineer and document, markup-based information systems that routinely subject their data sets to such rigorous specification and testing—and especially when built to standard specifications, enabling them to take advantage of commodity tools—have again and again proven to be both scalable, and more flexible over time, than single-layered systems handling media only in presentational (or application-specific) formats. The principles underlying this are exactly those that allow a factory to become more efficient and productive than individual craft workers, once basic problems of workflow, parts specification, machining and conformance testing are dealt with.”

It might have not happened this way were it not for a miserable, besieged yet brilliant and determined inventor who worked relentlessly for twenty years in buildings long-gone from a weed-choked island in the Shenandoah River at Harper’s Ferry, then-Virginia.

No one could really achieve true interchangeability of parts, until John Hall showed the world that the devil was in the myriad details and in a novel approach.

The Flintlock Musket

The thousands of broken American muskets on abandoned battlefields during the War of 1812 painfully drove home the need for replacement parts during battle.

The problem could be found in the workrooms of the federal armories in Harper’s Ferry and Springfield, MA. since their inceptions in 1798 and 1794 and respectively. Master gunsmiths and their apprentices made guns worthy by themselves but were not really interchangeable, because the eye inspection and the test firing did nothing to confirm if the weapon was interchangeable in its parts with every single other like gun made.

Col. Decius Wadsworth and his team of young West Point-graduated engineers – guided by Louis Tousard’s book “American Artillertists’ Companion.” – took charge of the work at the armories through the agency of U.S. Ordinance Department in 1815.

They challenged John Hall, who lived in his home state of Maine, to produce 200 of his

patented breech-loaded rifle within a five-month period that were truly interchangeable, as he claimed:

“Only one point now remains to bring the rifles to the utmost perfection, which I shall attempt if the Government contracts with me for the guns to any considerable amount viz , to make every similar part of every gun so much alike that. . . if a thousand guns were taken apart & the limbs thrown promiscuously together in one heap they may be taken promiscuously from the heap and will all come right,” Hall wrote them.

He added, hinting at the upfront cost of machine design: “This important point I conceive practiceable, & although in the first instance it will probably prove expensive, yet ultimately it will prove most economical & be attended with great advantages.”

The “probably prove expensive” disclaimer became Hall’s main challenge for the last fifteen years of his life.

Col. Wadsworth, and his promising assistant

Lt. George Bomford, then corralled the armories to make guns at least interchangeable between them, using models and gauges to replace the subjective inspection of a gunsmith’s naked eye.

They learned greater use of specialized machines and much more specified controls were needed. The achievements of contracted inventors Hall, Simeon North and Thomas Blanchard pointed the way.

Inventor Simeon North perfected a milling machine by using the model lock as a receiver gauge to which parts were fitted.

Thomas Blanchard was inspired by methods of turning of the French to create

Demonstration of a Blanchard Lathe

a novel gun stock-forming machine, that he presciently made to work with other specialized machines and specialized machine tools all within a larger sequence of production. The Harper’s Ferry armory placed an order for them in late 1818.

A favorable verdict from a three-month test, pitting Hall’s breech-loading rifle against a conventional muzzle-loading rifle landed him a smallish order to make a thousand of his rifles, the U.S. Model 1819 Hall Rifle. Hall moved to Harper’s Ferry and was granted his own private, manufactory along the Shenandoah River, outside the armory itself to do his contract work,

As the machine system gained favor in the mid-1820s, the Ordinance Department wanted Hall to focus less on just his patented, breech-loading rifle and more on his comprehensive approach to making anything to be truly interchangeable. The Harper’s Ferry/Shepherdstown region was rich in creative, frontier-bred gunsmiths who, Hall realized, he needed to design the prototypes for his machines and specialized tools.

By 1825 Blanchard and Hall, working under separate federal contracts pulled their independent ideas into even better shape with dramatic results at Harper’s Ferry.

Hall was late in delivering his breech-loading rifles because so much went into the how of making them.

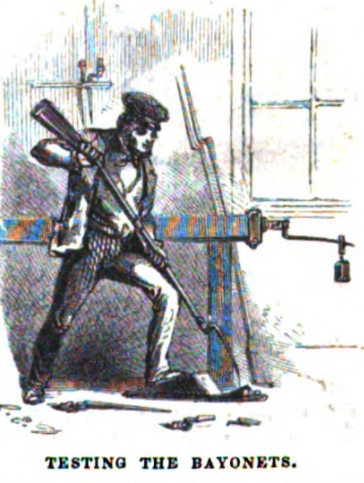

His chosen inspection gauges, for example, were in three sets – one for the workman, one for the foreman, one for the master armorer. And each was a set of 63 inspection gauges to make sure everything was to standard.

The system had the inspection gauge used throughout the manufacture, not just at the end. The gauges, wrote one mechanic at Harper’s Ferry: “were more numerous and exact . . .than had ever before been used.”

Hall’s real innovations were far too numerous and technical to be treated properly in a short article, the descriptions of which are unmatched against Merritt Roe Smith’s seminal work, “Harper’s Ferry Armory and the New Technology: The Challenge of Change,” Hall made great improvements, among many things, in creating the barrel, down to making allowances for the shrinkage of their being in the die.

He realized that having great power from water gave him the power to drive powerful machines that worked fast. He calibrated and directed that power to his ends.

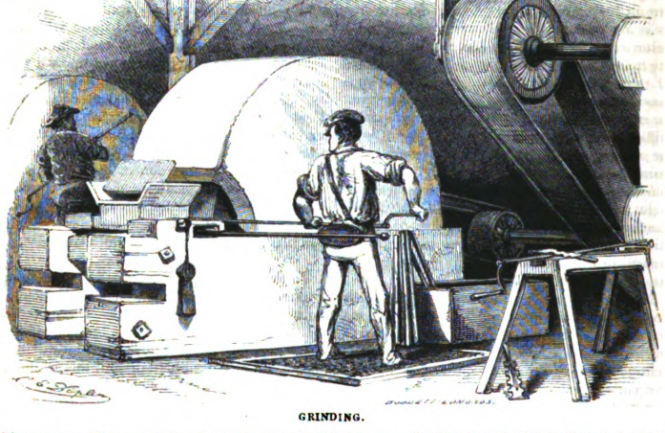

Hall transferred water power through a system of leather belts and pulleys to power his machines with unusual pace, greater than 3,000 revolutions per minute with efficiency, while most artisans used hand cutters and files. In every case, his system demanded absolute precision and discipline, however unpopular to some.

Almost two years past deadline but finished, Hall wrote of his fulfilled contract December, 1824, to Secretary of War John Calhoun:

“I have succeeded in an object which has hitherto completely baffled all the endeavors of those who have heretofore attempted it. I have succeeded in establishing methods for fabricating arms exactly alike and with economy, by the hands of common workmen and in such a manner as to endure a perfect observance of any established model and to furnish in the arms themselves a complete test of their conformity to it.”

Well, nothing so remarkable could be tolerated by Harper’s Ferry’s Old-Boy Network, a group of large land-owners in and around Harper’s Ferry that included the armory’s superintendent, James Stubblefield, who correctly saw Hall’s ascendancy as maybe abetting his own descendancy.

Inspector General John E. Wool wrote, in fact, a few years later, that Hall managed his Rifle Works “with great regularity, order, and system, whilst that of the Armory, (run by Stubblefield) was the reverse.”

Because Stubblefield’s politically-tinged, civilian position depended on keeping voting workers happy with high wages and low work pressures – a system Hall threatened by wanting a new system with fewer men – the Old-Boy-Network went to war against Hall to be rid of him.

A stream of falsehoods and slander began coming across the desks of the Secretary of War in Washington from Hall’s enemies: Ed Lucas, Alexander Beckham, and Stubblefield who even declared publicly that all of Hall’s work was not new.

They demanded an investigation thinking it would end Hall’s vastly improved fortunes.

The first investigation’s three evaluators spent three weeks studying the matter with all the pieces of many unmarked rifles at Fortress Monroe in late 1826. James Carrington; master machinist Luther Sage, and Virginia businessman, Col. James Bell submitted their finding, called “On Hall’s Machinery:”

“Captain Hall has formed & adopted a system, in the manufacture of small arms, entirely novel & which no doubt, may be attended with the utmost beneficial results to the Country, especially, if tried into effect on a large scale. . .his machines, for this purpose, are of several distinct classes, and are used for cutting iron & steel for executing wood work, all of which are essentially different from each other & differ materially from any other machines we have ever seen, in any other establishment.”

A contracted collaboration of both North and Hall working together in 1834 for the Ordinance Department produced results that forever confirmed the unequaled contributions of both men.

Smith’s verdict in his book on Hall:

“While countless individuals contributed to the new technology, John H. Hall stood foremost among those who combined inventiveness with entrepreneurial skill in blending men, machinery, and precision measurement methods into a working system of production. The achievement formed the taproot of modern industrialism.”

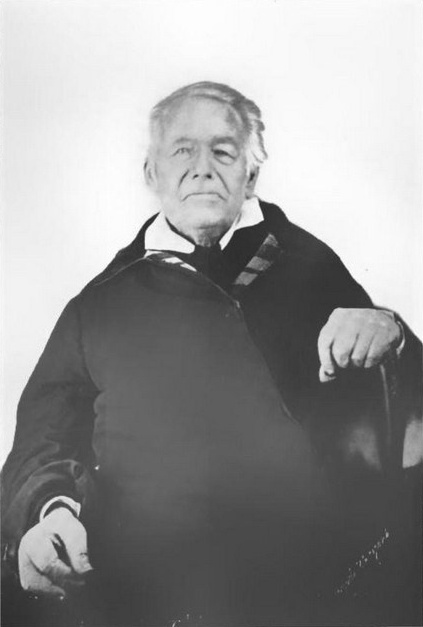

Brantz Mayer strolled Harper’s Ferry bemoaning:

“Nay, how much more beneficially would these hundreds of workmen be employed, if government devoted their labor to the manufacture of such un-picturesque instruments as

hoes, spades, rakes, axes, pitchforks, plows, and reaping machines; and if the army, which is to wield the perilous weapons that are strewn in every direction, were transmuted, under national patronage, into cultivators of those “homesteads” which politicians so cheaply vote them! But, alas! the soldier is epic, and the farmer only pastoral, and pageantry beats homeliness all the world over!

“These lackadaisical fancies floated through my mind as I walked over the half mile or armory; and I hope I may not be set down as “too progressive” or “Utopian,” if I divulge them in this public confessional.

“It was noon when we left the Armory and climbed to the fragment of Jefferson’s Rock, which affords the

“best coup d’oeil of this celebrated scenery. It was a fatiguing tramp under a mid-day sun, but we found a breeze singing down the gorge of the Shenandoah when we rested under the old pine-tree among the cliffs. “

Brantz Mayer could see the view from Jefferson’s Rock. If only he could see John Hall changed everything, not just guns.

Main References:

Abbot, Jacob. (July, 1852). “The Armory at Springfield.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. New York, NY: Harper and Bros. Vol. 5, Issue: 26. pp. 145-162.

Hounshell, David A. (1984). “From the American System to Mass Production to Mass Production 1800-1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States.” Baltimore, MD, London, UK: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Print.

Firearms technology and the original meaning of the Second Amendment, The Washington Post. by David Kopel April 3, 2017

Mayer, Brantz. (April, 1857). “June Jaunt.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. New York, NY: Harper and Bros. Vol. 14, Issue: 83. April, 1857. pp. 592-612.

Felicia Johnson Deyrup, “Arms Makers of the Connecticut Valley: A Regional Study of the Economic Development of the Small Arms Industry, 1798-1870.” (1948)

Piez, Wendell. (Spring, 2001). Beyond the “descriptive vs. procedural” distinction. Markup Languages: Theory and Practice, Vol. 3 no. 2. Print.

Ross Thomson, “Structures of Change in the Mechanical Age: Technological Innovation in the United States 1790-1865.” (2009)

Smith, Merritt R. (1977). “Harper’s Ferry Armory and the New Technology: The Challenge of Change.” Ithaca, NY, London, UK: Cornell University Press. Print.

David R. Meyer, “Networked Machinists: High-Technology Industries in Antebellum America.” (2006)

“Glossary of Firearms Terminology.” Wikipedia English.

Videos:

The Man Who Changed The World You Never Heard Of (1) – by Jim Surkamp & Eric Johnson TRT: 18:11

https://youtu.be/2qaaK5YwFX0

The Man Who Changed the World – You Never Heard Of (2) – by Jim Surkamp & Eric Johnson TRT: 25:23

https://youtu.be/DZ2IFf_mqvU

The Man Who Changed The World – You Never Heard Of – Conclusion TRT: 18:54

https://youtu.be/h2BkarHJsac

cannonmn. (23 Mar. 2009). Harper’s Ferry Armory and Inspection Gauges. Video posted to: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Zdu1G2nvjU

jsurkamp . (2 Jan. 2009). “Thomas Jefferson at Jefferson’s Rock 1783.” Video posted to: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lUDEEeqOwFQ