35,312 words

INTRODUCTION

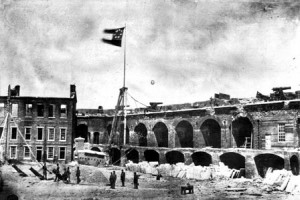

This is where things fell apart. And Sumter.

More than one historian has called the conclusion of the Virginia Secession Convention in April, 1861 the most fateful moment in American history.

What a story. This is a chronology of eyewitness accounts and direct quotes of this tumultuous and very pivotal event. The personalities and intrigues are just one second and inch shy of blood on the floor. What happened starting the night of April 16th – the night before the vote on whether to secede – Henry Wise and John Imboden did what we nowadays call “hatching a coup.” Now, I’m not complaining – a war was starting up – but they too saw what they were doing in those terms at the time of execution.

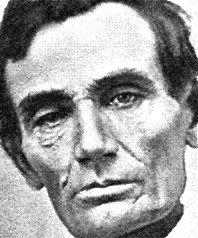

The most interesting revelation for me from this convention and the war’s parallel inception was Wise’s reaction to first seeing from his clerk the news of Lincoln’s proclamation for volunteers from Virginia on April 15: “in utter disbelief,” according to his clerk. Before that moment, Wise acted fiercely on a belief that a strong, belligerent demonstration would make Lincoln back down and pave the way for Virginia to leave the Union. What a fateful, costly mis-read. As some say: “Bully meets bully; people get hurt.”

What also makes this story fascinating and sobering is that – minute-by-minute the world ending, the silent ones, even, will say they’re sad. Proud men bared their souls and emptied their hearts – no doubt shedding tears – because their world was ending – the United States. Existential sorrow hollowed solemn voices as the same Henry Wise brandished a long-barreled horse pistol in their faces, saying the war had already begun and by his own hand.

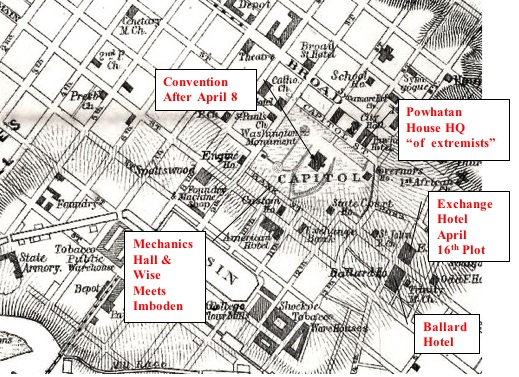

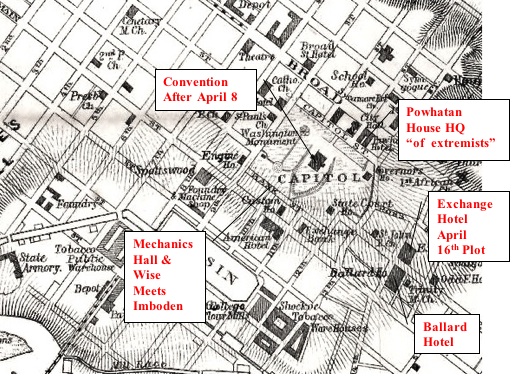

Virginia began really splitting, when West Virginians decided to leave the convention, such as when the forceful John Carlile of Harrison County hurried quietly out of Richmond to catch an early train on the edge of town, while men with hangin’ rope were searching for him in the halls of the Ballard Hotel.

“West” Virginia wasn’t “born” at the close of the Virginia Convention in April, 1861, but its contractions began then and there.

The rough treatment of western Virginia’s Convention delegates forged a will for them to “go west” once and for all as a matter of survival. And Jefferson County, whose two delegates never voted for secession during the proceeding, would see the first insurrection force marching on Harper’s Ferry before the work of secession was even formally authorized. It was the beginning of Jefferson County’s unique tragedy – of being pulled along the tear between both east and west Virginia for many years to come.

All in all, this is a tale of human nature that is timeless, of how close by potential anarchy always dwells, only requiring our carelessness and hubris. You can lose everything like awaking from a dream, in a spell of white hot passion, that also is awakened from, much later, by a cold morning.

If this story is the In-Between, then the Beginning and the End to the story of Jefferson County entering West Virginia, both are in the unwavering person of George Koonce, the focus of the next post.- Jim Surkamp

2 VIRGINIAS – THE COMET SPLITS THEM – APRIL, 17, 1861

ACT I – JEFFERSON VOTES UNIONISTS TO SECESSION CONVENTION

ACT II – CONVENTION UNIONISTS WITHSTAND VERBAL OFFENSIVE

ACT III – TWO ILL-TIMED VISITS TO LINCOLN

ACT IV – FIRST FLAME OF WAR

ACT V – THE WISE-IMBODEN COUP

ACT VI – THE MAY 23 REFERENDUM VOTE IS FOR SECESSION, BUT CLOUDED BY A COUP AND WAR

ACT VII – THE WILL IS FORGED FOR A “WEST” VIRGINIA

ACT I – JEFFERSON COUNTY VOTES 2 UNIONISTS TO SECESSION CONVENTION

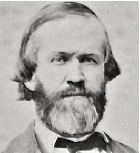

William Lucas, Logan Osburn, Andrew Hunter, Alfred Barbour

P. Douglas Perks writes:

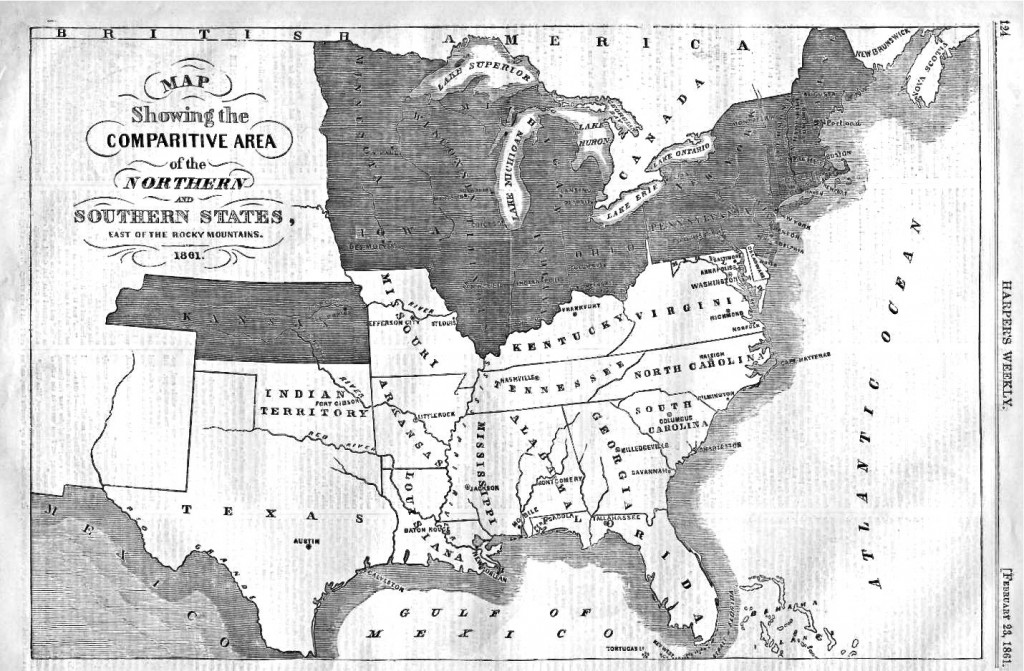

Soon Mississippi, then Florida and Alabama followed South Carolina out of the Union. But, the question on the collective mind of a now divided nation was, “How goes Virginia?”

The answer to that question would soon be forthcoming. Governor John Letcher called for a special session of the Virginia General Assembly to be held on Monday, January 14th, 1861. The purpose of the session was to determine Virginia’s position on the issue of secession from the Union. The General Assembly decided that Virginia’s position would be determined at a state-wide convention to be held on Wednesday, February 13th, 1861. Each county would elect delegates to attend the convention. The convention was empowered to debate the issue of secession and make a proposal which then had to be ratified by a statewide referendum.

According to Millard Bushong, “the most important meeting ever held” in Jefferson County occurred on Monday, January 21st, 1861.10 On that date the same men who had just two months earlier cast their votes in the presidential election met at the Jefferson County Court House. They assembled at a public meeting to determine who would represent Jefferson County at the upcoming Virginia Secession Convention.

The results of the meeting were announced in the Alexandria Gazette:

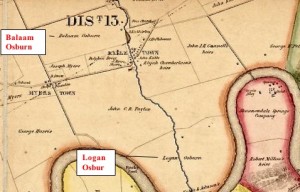

The Southern Rights party in Jefferson Co., Va., has nominated the Hon. Wm. Lucas and Andrew Hunter, esq., as candidates for the State Convention. The Union party in the same county have nominated Col. A. M. Barbour and Logan Osborne, esq.

The men who supported States’ rights were represented by two men well known in Jefferson County.

William Lucas was a member of one of Jefferson’s oldest families. Born on November 30th, 1800 at Cold Spring just south of Shepherd’s Town, Lucas studied law under Henry Berry of Shepherd’s Town and Judge Henry St. George Tucker in Winchester. Lucas married Sarah Rion and in 1826 they inherited Rion Hall and oversaw its expansion. Upon Sarah’s death, Lucas married

Virginia Bedinger, the daughter of Daniel Bedinger. They were the parents of

Judge Daniel Bedinger Lucas. Lucas practiced law first in Shepherd’s Town then in Charlestown. He was a delegate to the Virginia General Assembly in 1837-1838 and represented Virginia’s 15th Congressional District in 1839-1841. Lucas was a delegate from Jefferson County to the Virginia Constitution Convention held in 1850-1851.

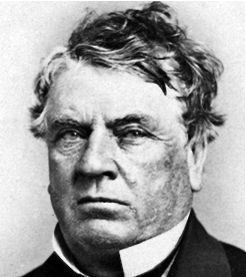

Lucas’ running mate was local attorney Andrew Hunter, well known in the county for his role in the prosecution of John Brown. Hunter was born March 22nd, 1804 in Berkeley County the son of Colonel David H. and Elizabeth Pendleton Hunter. Hunter graduated from Hampden-Sydney College and then studied law. In the 1850s, he built Hunter Hill on the east border of Charlestown. Hunter practiced first in Harper’s Ferry then in Charlestown. He was a Whig presidential elector in 1840, a member of the Virginia General Assembly in 1846, and the Virginia Constitution Convention in 1850-1851. Lucas and Hunter were running opposite two men who represented the Union Party.

Alfred Madison Barbour was born April 17th, 1829 in Culpeper County, Virginia into one of Virginia’s oldest families. Barbour was a graduate of the University of Virginia and Harvard University School of Law. He began his practice of law in Charlestown. On December 24th, 1858 Barbour was appointed superintendent of the United States Armory at Harper’s Ferry. He was immediately faced with severe budget cuts, but Barbour handled the crisis well and earned good marks from his superiors at the Ordnance Department. In October 1859 at the time of John Brown’s attack on the armory, Barbour was in New England visiting the Springfield Armory and the Ames Manufacturing Company. He learned of the raid while visiting Samuel Colt in Hartford, Connecticut. He hurried home to Jefferson County and arrived back in Harper’s Ferry on October 21st. Archibald Kitzmiller, the acting superintendent, Master Armorer Benjamin Mills, and Master Machinist Armistead Ball had all had been held hostage by Brown and his men. Barbour was left with the task of restoring calm and order after the three day siege.

The other pro-Union candidate was Logan Osburn. Osburn was born March 23rd, 1810 in Loudoun County, Virginia. He received his education at the Catoctin Academy located in Loudoun County. In the 1830s after he married Hanna Leslie the Osburn’s moved to Ohio. There he pursued a number of vocations including newspaper editor and hotel operator. After the death of his wife, Osburn returned to Virginia where, in 1840, he married Margaret Chew Osburn. In 1843, the Osburn family moved to Jefferson County. Osburn bought the property in the Kabletown district known as Avon Bend. While the house was being renovated Osburn owned and operated a store in Kabletown. The Osburn family moved to Avon Bend in 1848. From 1851-1852 he co-owned Shannondale Springs. In 1856, Osburn built and moved his family to Avon View. Osburn represented Jefferson County in the Virginia General Assembly from 1857 to 1858.

PERKS CONTINUED:

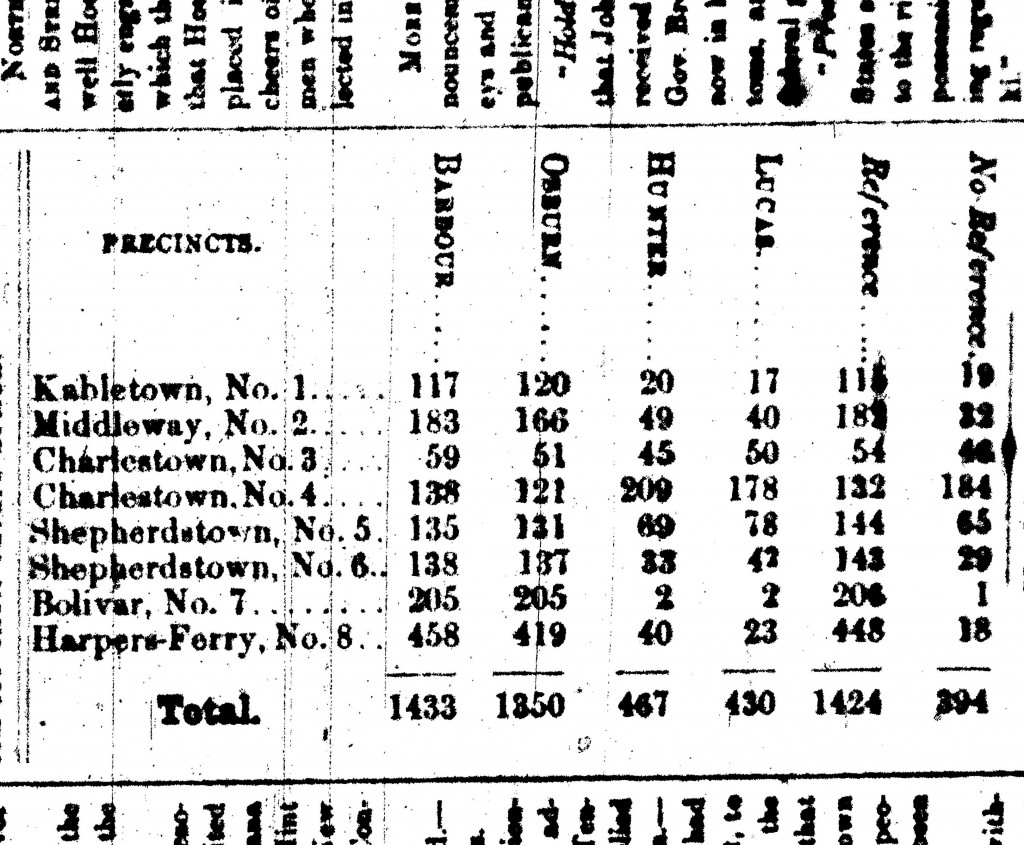

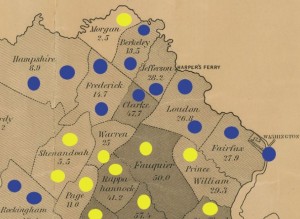

Monday, February 4th, 1861 was the day designated by the Virginia General Assembly for each county to select its delegates to the Secession Convention. Jefferson’s electorate once again went to the polls. Consistent with the results of the presidential election, the men of Jefferson County voiced their support of the Constitution. Barbour and Osburn captured 1,433 votes and 1,350 votes respectively. Hunter’s 467 votes and Lucas’ total of 430 votes confirmed that in early February 1861 Jefferson County wanted to remain in the Union and would send two men to Richmond who would vote in opposition to secession.

The three-month period from the first of February to the end of April in 1861 is arguably the most important 90 days in our Nation’s history. During those 2,160 hours, men from around the Commonwealth met to debate and to decide Virginia’s fate.

Among the document archives at the Jefferson County Museum is a collection of Logan Osburn’s correspondence. Included in the collection are several letters written by Osburn during this critical time in history. Reading Osburn’s observation of how events transpired during Virginia’s convention affords us a front row seat as history is being made. (Perks, pp. 74-77)

ACT II – UNIONISTS CONTROL THE CONVENTION, WILLEY AND CARLILE “ANSWER” POWERFUL SPEECHES BY INVITED SECESSION LOBBYISTS ANDERSON, BENNING AND PRESTON. MEANTIME, PRESIDENT-ELECT LINCOLN GIVES HINTS OF HIS POLICIES IN PUBLIC STATEMENTS. BUT AT THE CONVENTION ON APRIL 4TH, RIGHT AFTER A SWEEPING PRO-UNION VOTE REJECTING SECESSION, THE UNIONISTS OVERLOOK A GOLDEN MOMENT TO PREVENT SECESSION ALTOGETHER – AND FAIL TO PLAY THEIR ULTIMATE CARD – ADJOURNMENT SINE DIE.

Willey, Preston Smith, youth, Carlile, F. Anderson, Benning

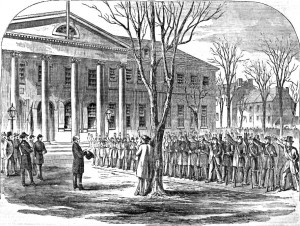

February 13 – Wednesday, Richmond, VA: First Day of the Convention

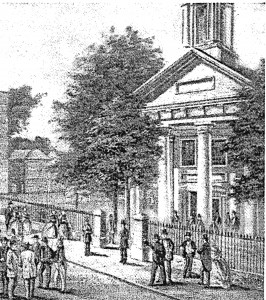

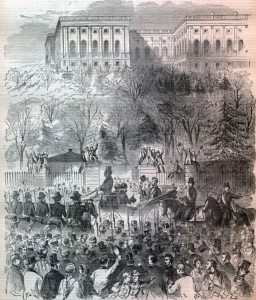

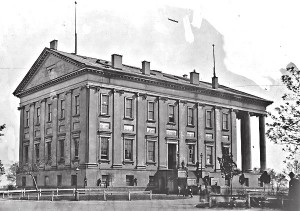

The Virginia Secession Convention opened on Wednesday, February 13th, 1861 in Richmond, Virginia. The Mechanics Institute at the foot of Capitol Square

was selected to be the convention site. John Janney, delegate from Loudoun County, was elected president of the convention. Janney’s opening remarks set the tone for the convention:

It is our duty on an occasion like this to elevate ourselves into an atmosphere, in which party passion and prejudice cannot exist-to conduct all our deliberations with calmness and wisdom, and to maintain, with inflexible firmness, whatever position we may find it necessary to assume. (Perks, pp. 74-77)

The Virginia State Convention assembles in the Hall of the House of Delegates, and elects Mr. Cox as temporary Chairman. Mr. Gordon, Clerk of the House of Delegates, is appointed temporary Secretary.

The roll is called. Mr. Janney is elected President of the Convention, and makes a speech of acceptance. Mr. Eubank is elected Secretary. The Convention adopts for the time being the rules of the House of Delegates.

February 18 – Monday, Richmond, VA: Fifth Day of the Convention

Mr. Fulton Anderson, commissioner from Mississippi, addresses the Convention; he justifies the secession of his state, and invites Virginia to the leadership of a Southern Union. Mr. Benning, commissioner from Georgia, speaks in the same vein, with frequent reference to economic considerations. (NOTE: The comments regarding race by speakers Anderson, Benning, and Preston are presented with the understanding that they are considered unacceptable in a modern civilized society.-ED)

ACT II – SCENE I – LOBBYIST FROM MISSISSIPPI SECESSION COMMISSIONER FULTON ANDERSON SPEAKS: But we in Mississippi, gentlemen, are no longer under that illusion. Hope has died in our hearts. It received its death-knell at the fatal ballot-box in November last . . .

{THE COMMISSIONER FROM MISSISSIPPI

The President stated that in pursuance of the resolution of Friday last, he begged leave to announce to the Convention, that the Hon. FULTON ANDERSON, the Commissioner from Mississippi, would now address them:

Mr. ANDERSON ascended the platform near the President’s Chair, and addressed the Convention, as follows:

Mr. ANDERSON:

Gentlemen of the Convention: Honored by the Government of Mississippi with her commission to invite your co-operation in the measures she has been compelled to adopt for the vindication of her rights and her honor in the present perilous crisis of the country, I desire to express to you, in the name and behalf of her people, the sentiments of esteem and admiration which they in common with the whole Southern people entertain for the character and fame of this ancient and renowned Commonwealth.

. . . In recurring to our past history, we recognize the State of Virginia as the leader in the first great struggle for independence; foremost not only in the vindication of her own rights, but in the assertion and defence of the endangered liberties of her sister colonies; and by the eloquence of her orators and statesmen, as well as by the courage of her people arousing the whole American people in resistance to British aggression.

. . . I desire also to say to you gentlemen, that in being compelled to sever our connexion with the government which has hitherto united us, the hope which lies nearest to our hearts is that, at no distant day, we may be again joined with you in another Union, which shall spring into life under more favorable omens and with happier auspices than that which has passed away . . .

. . . On the 29th of November last, the Legislature of Mississippi, by an unanimous vote, called a Convention of her people, to take into consideration the existing relations between the Federal Government and herself, and to take such measures for the vindication of her sovereignty and the protection of her institutions as should appear to be demanded.

. . . As early as the 10th of February, 1860, her Legislature had, with the general approbation of her people, adopted the following resolution:

“Resolved, That the election of a President of the United States by the votes of one section of the Union only, on the ground that there exists an irrepressible conflict between the two sections in reference to their respective systems of labor and with an avowed purpose of hostility to the

institution of slavery, as it prevails in the Southern States, and as recognized in the compact of Union, would so threaten a destruction of the ends for which the Constitution was formed, as to justify the slave-holding States in taking council together for their separate protection and safety.”

This was the ground taken, gentlemen, not only by Mississippi, but by other slave-holding States, in view of the then threatened purpose, of a party founded upon the idea of unrelenting and eternal hostility to the institution of slavery, to take possession of the power of the Government and use it to our destruction. It cannot, therefore, be pretended that the Northern people did not have ample warning of the disastrous and fatal consequences that would follow the success of that party in the election, and impartial history will emblazon it to future generations, that it was their folly, their recklessness and their ambition, not ours, which shattered into pieces this great confederated Government, and destroyed this great temple of constitutional liberty which their ancestors and ours erected, in the hope that their descendants might together worship beneath its roof as long as time should last.

But, in defiance of the warning thus given and of the evidences so cumulated from a thousand other sources, that the Southern people would never submit to the degradation implied in the result of such an election, that sectional party, bounded by a geographical line which excluded it from the possibility of obtaining a single electoral vote in the Southern States, avowing for its sentiment, implacable hatred to us, and for its policy the destruction of our institutions, and appealing to Northern prejudice, Northern passion, Northern ambition and Northern hatred of us, for success, thus practically disfranchizing the whole body of the Southern people, proceeded to the nomination of a candidate for the Presidency who, though not the most conspicuous personage in its ranks, was yet the truest representative of its destructive principles.

The steps by which it proposed to effect its purposes, the ultimate extinction of slavery, and the degradation of the Southern people, are too familiar to require more than a passing allusion from me.

. . . Having thus placed the institution of slavery, upon which rests not only the whole wealth of the Southern people, but their very social and political existence, under the condemnation of a government established for the common benefit, it proposed in the future, to encourage immigration into the public Territory, by giving the public land to immigrant settlers, so as, within a brief time, to bring into the Union free States enough to enable it to abolish slavery within the States themselves.

I have but stated generally the outline and the general programme of the party to which I allude without entering into particular details or endeavoring to specify the various forms of attack, which have been devised and suggested by the leaders of that party upon our institutions.

That this general statement of its purposes is a truthful one, no intelligent observer of events will for a moment deny; but the general view and purpose of the party has been sufficiently developed by the President elect.

“It is my opinion,” says Mr. Lincoln, “that the slavery agitation will not cease until a crisis shall have been reached and passed. A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently, half slave and half free. I do not expect the house to fall, but I expect it to cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all another. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest its further spread and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, or its advocates will push it forward until it shall become alike lawful in all the States—old as well as new, North as well as South.”

. . . We, the descendants of the leaders of that illustrious race of men who achieved our independence and established our institutions, were to become a degraded and a subject class, under that government which our fathers created to secure the equality of all the States—to bend our necks to the yoke which a false fanaticism had prepared for them, and to hold our rights and our property at the sufferance of our foes, and to accept whatever they might choose to leave us as a free gift at the hands of an irresponsible power, and not as the measure of our constitutional rights.

All this, gentlemen, we were expected to submit to, under the fond illusion that at some future day, when our enemies had us in their power, they would relent in their hostility; that fanaticism would pause in its career without having accomplished its purpose; that the spirit of oppression would be exorcised, and, in the hour of its triumph, would drop its weapons from its hands, and cease to wound its victim. We were expected, in the language of your own inspired orator, to “indulge in the fond illusions of hope; to shut our eyes to the painful truth, and listen to the song of that syren until it transformed us into beasts.”

ANDERSON CONTINUED

But we in Mississippi, gentlemen, are no longer under that illusion. Hope has died in our hearts. It received its death-knell at the fatal ballot-box in November last, and the song of the syren no longer sounds in our ears. We have thought long and maturely upon this subject, and we have made up our minds as to the course we should adopt. We ask no compromise and we want none. We know that we should not get it if we were base enough to desire it, and we have made the irrevocable resolve to take our interests into our own keeping.

Could we think that the crisis which is now upon us was but a temporary ebullition of temper in one section of the country, which would in brief time subside, we might even yet believe that all was not lost, and that we might yet rest securely under the shadow of the Constitution. But the stern truth of history, if we accept its teachings, forbids us such reflections. It is not to be denied that the sentiment of hatred to our institutions in the Northern section of the Confederacy is the slow and mature growth of many years of false teaching, and that as we receded further and further from the earlier and purer days of the Republic, and from the memory of associated toils and perils in a common cause which once united us, that sentiment of hatred has been fanned from a small spark into a mighty conflagration, whose unextinguishable and devouring flames are reducing our empire into ashes.

ANDERSON CONTINUED

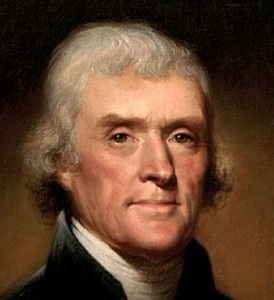

Ere yet that generation which achieved our liberty had passed entirely from the scene of action, it manifested itself in the Missouri controversy. Then were heard the first sounds of that fatal strife which has raged, with occasional intermissions, down to this hour. And so ominous was it of future disaster, even in its origin, that it filled even the sedate soul of Mr. Jefferson with alarm ; he did not hesitate to pronounce it, even then, as the death-knell of the Union, and in mournful and memorable words to congratulate himself that he should not survive to witness the calamities he predicted.

Said he :“This momentous question, like a fire-bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. It is hushed, indeed, for the present, but that is only a reprieve, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once concurred in and held up to the passions of men, will never be obliterated, and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper, until it will kindle such mutual and mortal hatred as to render separation preferable to eternal discord. I regret that I am now to die in the belief that the useless sacrifice of themselves by the generation of 1776, to acquire self-government and happiness for their country, is to be thrown away by the unwise and unworthy passions of their sons, and that my only consolation is to be that I live not to weep over it.”

But, so far were the Northern people from being warned by these sad prophetic words, that at each renewal of the struggle the sentiment of hostility has acquired additional strength and intensity. . . An infidel fanaticism, crying out for a higher law than that of the Constitution and a holier Bible than that of the Christian, has been enlisted in the strife, and in every form in which the opinions of a people can be fixed and their sentiments perverted. In the schoolroom, the pulpit, on the rostrum, in the lecture-room and in the halls of legislation, hatred and contempt of us and our institutions, and of the Constitution which protects them, have been inculcated upon the present generation of Northern people. Above all, they have been taught to believe that we are a race inferior to them in morality and civilization, and that they are engaged in a holy crusade for our benefit in seeking the destruction of that institution which they consider the chief impediment to our advance, but which we, relying on sacred and profane history for our belief in its morality, believe lies at the very foundation of our social and political fabric and constitutes their surest support.

This, gentlemen, is indeed an irrepressible conflict which we cannot shrink from if we would; and though the President elect may congratulate himself that the crisis is at hand which he predicted, we, if we are true to ourselves, will make it fruitful of good by ending forever the fatal struggle and placing our institutions beyond the reach of further hostility.

ANDERSON CONTINUED

. . .This is the inevitable destiny of the Southern people, and this destiny Virginia holds in her hands. By uniting herself to her sisters of the South who are already in the field, she will make that a peaceful revolution which may otherwise be violent and bloody. At the sound of her trumpet in the ranks of the Southern States, “grim-visaged war will smooth his wrinkled front,” peace and prosperity will again smile upon the country, and we shall hear no more threats of coercion against sovereign States asserting their independence. The Southern people, under your lead, will again be united, and liberty, prosperity and power, in happy union, will take up their abode in the great Southern Republic, to which we may safely entrust our destinies. These are the noble gifts which Virginia can again confer on the country, by prompt and decided action at the present.

In conclusion, gentlemen, let me renew to you the invitation of my State and people, to unite and co-operate with your Southern sisters who are already in the field, in defence of their rights. We invite you to come out from the house of your enemies, and take a proud position in that of your friends and kindred. Come and be received as an elder brother whose counsels will guide our action and whose leadership we will willingly follow. Come and give us the aid of your advice in counsel and your arm in battle, and be assured that when you do come, as we know you will do at no distant day, the signal of your move will send a thrill of joy vibrating through every Southern heart, from the Rio Grande to the Atlantic, and a shout of joyous congratulation will go up which will shake the continent from its centre to its circumference.}

ACT II – SCENE II – GEORGIA’S HENRY L. BENNING ON THE NEED FOR SECESSION:

By the time the North shall have attained the power, the black race will be in a large majority, and then we will have black governors, black legislatures, black juries, black everything.

{The PRESIDENT—

In further execution of the order of the day, I have the honor of introducing to you the Hon. HENRY L. BENNING, of Georgia.

Mr. BENNING came forward and said:

Mr. President and Members of the Convention:

I have been appointed by the Convention of the State of Georgia, to present to this Convention, the ordinance of secession of Georgia, and further, to invite Virginia, through this Convention, to join Georgia and the other seceded States in the formation of a Southern Confederacy. This, sir, is the whole extent of my mission. I have no power to make promises, none to receive promises; no power to bind at all in any respect. But still, sir, it has seemed to me that a proper respect for this Convention requires that I should with some fulness and particularity, exhibit before the Convention the reasons which have induced Georgia to take that important step of secession, and then to lay before the Convention some facts and considerations in favor of the acceptance of the invitation by Virginia. With your permission then, sir, I will pursue this course.

What was the reason that induced Georgia to take the step of secession? This reason may be summed up in one single proposition. It was a conviction, a deep conviction on the part of Georgia, that a separation from the North was the only thing that could prevent the abolition of her slavery. This conviction, sir, was the main cause. It is true, sir, that the effect of this conviction was strengthened by a further conviction that such a separation would be the best remedy for the fugitive slave evil, and also the best, if not the only remedy, for the territorial evil. But, doubtless, if it had not been for the first conviction this step would never have been taken. It therefore becomes important to inquire whether this conviction was well founded.

Is it true, then, that unless there had been a separation from the North, slavery would be abolished in Georgia? I address myself to the proofs of that case.

In the first place, I say that the North hates slavery, and, in using that expression I speak wittingly. In saying that the Black Republican party of the North hates slavery, I speak intentionally. If there is a doubt upon that question in the mind of any one who listens to me, a few of the multitude of proofs which could fill this room, would, I think, be sufficient to satisfy him. I beg to refer to a few of the proofs that are so abundant; and ***the first that I shall adduce consists in two extracts

from a speech of Lincoln’s, made in October, 1858. They are as follows: “I have always hated slavery as much as any abolitionist; I have always been an old line Whig; I have always hated it and I always believed it in the course of ultimate extinction, and if I were in Congress and a vote should come up on the question, whether slavery should be excluded from the territory, in spite of the Dred Scott decision, I would vote that it should.”

These are pregnant statements; they avow a sentiment, a political principle of action, a sentiment of hatred to slavery as extreme as hatred can exist. *** The political principle here avowed is, that his action against slavery is not to be restrained by the Constitution of the United States, as interpreted by the Supreme Court of the United States. I say, if you can find any degree of hatred greater than that, I should like to see it. This is the sentiment of the chosen leader of the Black Republican party ; and can you doubt that it is not entertained by every solitary member of that same party? You cannot, I think. He is a representative man; his sentiments are the sentiments of his party; his principles of political action are the principles of political action of his party. I say, then; it is true, at least, that the Republican party of the North hates slavery.

My next proposition is, that the Republican party of the North is in a permanent majority. It is true that in a government organized like the government of the Northern States, and like our own government, a majority, where it is permanent, is equivalent to the whole. The minority is powerless if the majority be permanent. Now, is this majority of the Republican party permanent? I say it is. That party is so deeply seated at the North that you cannot overthrow it. It has the press, it has the pulpit, it has the school-house, it has the organizations—the Governors, Legislatures, the judiciary, county officers, magistrates, constables, mayors, in fact all official life. Now, it has the General Government in addition. It has that inexhaustible reserve to fall back upon and to recruit from, the universal feeling at the North that slavery is a moral, social and political evil. With this to fall back upon, recruiting is easy. This is not all. The Republican party is now in league with the tariff, in league with internal improvements, in league with three Pacific Railroads. Sir, you cannot overthrow such a party as that. As well might you attempt to lift a mountain out of its bed and throw it into the sea.

BENNING CONTINUED

But, suppose, sir, that by the aid of Providence and the intensest human exertion, you were enabled to overthrow it, how long would your victory last? But a very short time. The same ascendancy which that party has gained now, would be gained again before long. If it has come to this vast majority in the course of twenty-five years, from nothing, how long would it take the fragments of that party to get again into a majority? Sir, in two or three Presidential elections your labor would be worse than the labor of Sisyphus, and every time you rolled the rock up the hill it would roll back again growing larger and larger each time until at last it would roll back like an avalanche crushing you beneath it.

The Republican party is the permanent, dominant party at the North, and it is vain to think that you can put it down. It is true that the Republican party hates slavery, and that it is to be the permanent, dominant party at the North ; and the majority being equivalent to the whole, as I have already stated, we cannot doubt the result. What is the feeling of the rest of the Northern people upon this subject? Can you trust them? They all say that slavery is a moral, social and political evil. Then the result of that feeling must be hatred to the institution; and if that is not entertained, it must be the consequence of something artificial or temporary—some interest, some thirst for office, or some confidence in immediate advancement. And we know that these considerations cannot be depended upon, and we may expect that, ultimately, the whole North will pass from this inactive state of hatred into the active state which animates the Black Republican party.

Is it true that the North hates slavery? My next proposition is that in the past the North has invariably exerted against slavery, all the power which it had at the time. The question merely was what was the amount of power it had to exert against it. They abolished slavery in that magnificent empire which you presented to the North ; they abolished slavery in every Northern State, one after another ; they abolished slavery in all the territory above the line of 36 30, which comprised about one million square miles. They have endeavored to put the Wilmot Proviso upon all the other territories of the Union, and they succeeded in putting it upon the territories of Oregon and Washington. They have taken from slavery all the conquests of the Mexican war, and appropriated it all to anti-slavery purposes ; and if one of our fugitives escapes into the territories, they do all they can to make a free man of him; they maltreat his pursuers, and sometimes murder them. They make raids into your territory with a view to raise insurrection, with a view to destroy and murder indiscriminately all classes, ages and sexes, and when the base perpetrators are caught and brought to punishment, condign punishment, half the north go into mourning. If some of the perpetrators escape, they are shielded by the authorities of these Northern States—not by an irresponsible mob, but by the regularly organized authorities of the States.

My next proposition is, that we have a right to argue from the past to the future and to say, that if in the past the North has done this, in the future, if it shall acquire the power to abolish slavery, it will do it.

BENNING CONTINUED

My next proposition is that the North is in the course of acquiring this power to abolish slavery. Is that true? I say, gentlemen, the North is acquiring that power by two processes, one of which is operating with great rapidity—that is by the admission of new States. The public territory is capable of forming from twenty to thirty States of larger size than the average of the States now in the Union. The public territory is peculiarly Northern territory, and every State that comes into the Union will be a free State. We may rest assured, sir, that that is a fixed fact. The events in Kansas should satisfy every one of the truth of that. If causes now in operation are allowed to continue, the admission of new States will go on until a sufficient number shall have been secured to give the necessary preponderance to change the Constitution. There is a process going on by which some of our own slave States are becoming free States already. It is true, that in some of the slave States the slave population is actually on the decrease, and, I believe it is true of all of them that it is relatively to the white population on the decrease. The census shows that slaves are decreasing in Delaware and Maryland ; and it shows that in the other States in the same parallel, the relative state of the decrease and increase is against the slave population. It is not wonderful that this should be so. The anti-slavery feeling has got to be so great at the North that the owners of slave property in these States have a presentiment that it is a doomed institution, and the instincts of self-interest impels them to get rid of that property which is doomed. The consequence is, that it will go down lower and lower, until it all gets to the Cotton States—until it gets to the bottom. There is the weight of a continent upon it forcing it down. Now, I say, sir, that under this weight it is bound to go down unto the Cotton States, one of which I have the honor to represent here. When that time comes, sir, the free States in consequence of the manifest decrease, will urge the process with additional vigor, and I fear that the day is not distant when the Cotton States, as they are called, will be the only slave States. When that time comes, the time will have arrived when the North will have the power to amend the Constitution, and say that slavery shall be abolished, and if the master refuses to yield to this policy, he shall doubtless be hung for his disobedience.

My proposition, then, I insist, is true, that the North is acquiring this power. That being so, the only question is will she exercise it? Of course she will, for her whole course shows that she will. If things are allowed to go on as they are, it is certain that slavery is to be abolished except in Georgia and the other cotton States, and I doubt, ultimately in these States also. By the time the North shall have attained the power, the black race will be in a large majority, and then we will have black governors, black legislatures, black juries, black everything. (Laughter.) The majority according to the Northern idea, which will then be the all-pervading, all powerful one, have the right to control. It will be in keeping particularly with the principles of the abolitionists that the majority, no matter of what, shall rule. Is it to be supposed that the white race will stand that? It is not a supposable case. Although not half so numerous, we may readily assume that war will break out everywhere like hidden fire from the earth, and it is probable that the white race, being superior in every respect, may push the other back. They will then call upon the authorities at Washington, to aid them in putting down servile insurrection, and they will send a standing army down upon us, and the volunteers and Wide-Awakes will come in thousands, and we will be overpowered and our men will be compelled to wander like vagabonds all over the earth; and as for our women, the horrors of their state we cannot contemplate in imagination. That is the fate which Abolition will bring upon the white race.

But that is not all of the Abolition war. We will be completely exterminated, and the land will be left in the possession of the blacks, and then it will go back into a wilderness and become another Africa or St. Domingo. The North will then say that the Lord made this earth for his Saints and not for Heathens, and we are his Saints, and the Yankees will come down and drive out the negro.

Sir, this is Abolition to the cotton States. Would you blame us if we sought a remedy to avert that condition of things? What must be the requisites of any remedy that can do it? It must be one which will have one of two qualities. It must be something that will change the unanimity of the North on the slavery question, or something that shall take from them the power over the subject. Any thing that does not contain one of these two requisites is not a remedy for the case; it does not come to the root of the disease.

BENNING CONTINUED

What remedy is it that contains these requisites? Is there any in the Union that does? Let us take the strongest that we have heard suggested, which is an amendment of the Constitution guaranteeing the power of self-preservation, of dividing the public territory at the line of 36 deg. 30 min., giving the South all below that line. I know that remedy has not been thought of as in any degree practicable. But, let us look at it. Suppose they grant us the power of self-preservation—suppose they give to each Senator and member the veto power over any bill relating to slavery. That is putting it strong enough. Would that be sufficient now, to make it protective? I say it would not, and for two reasons. The first is that the North regards every such stipulation as void under the higher law. The North entertains the opinion that slavery is a sin and a crime. I mean, when I say the North, the Republican party, and that is the North ; and they say that any stipulation in the Constitution or laws in favor of slavery, is an agreement with death and a covenant with hell ; and that it is absolutely a religious merit to violate it. They think it as much a merit to violate a provision of that sort, as a mere stipulation in favor of murder or treason.

Well, sir, a people entertaining this opinion of a covenant of that sort, is beyond the pale of contract-making. You cannot make a contract with a people of that kind, because it is a bond not as they regard it, binding upon them. That being so, how will it be any protection to us, that our senators and representatives shall have the power of saying this bill shall not pass. Suppose the bill to pass giving protection to slavery, they would say hereafter, we proclaimed from the mountain tops, from the hustings, from the forum, and wherever our voice could be heard, that we did not regard stipulations in matters relating to slavery as binding upon us. We recognize a higher law, and will not obey these stipulations—you might have so expected from our proclaimed opinions beforehand.

The next reason is this, the North entertains upon the subject of the Constitution the idea that this a consolidated Government, that the people are one nation, not a Confederation of States, and that being a consolidated Government, the numerical majority is sovereign. The necessary result of that doctrine when pushed to its natural result is, that the Constitution of the United States is, at any time, subject to amendment by a bare majority of the whole people; and that being so, it becomes no matter what protection the Constitution may contain, it would be changed by a majority of the people, because a stipulation in the Constitution can no more be binding upon those who may choose subsequently to alter it, than the act of a legislature upon a subsequent legislature. Thus it is they will have the power to change the Constitution, alter it as you will. The President elect has proclaimed from the house tops in Indiana that a State is no more than a county. This is an abandonment in the concrete of the whole doctrine. How, then, can we accept any stipulation from a people holding the opinions that they do upon the question of slavery, and the obligations of government. The proposition which I have already adduced for argument sake, is infinitely beyond anything that we have a hope of obtaining. Then I assume that if this be true, it must be true that you can get no remedy for this disease in the Cotton States of the Union.

The question then is, would a separation from the North be a remedy? I say it would be a complete remedy; a remedy that would reach the disease in all its parts. If we were separated from the North, the will of the North on the subject of slavery would be changed. Why is it now that the North hates slavery? For the reason that they are, to some extent, responsible for the institution because of the Union, and for the reason that by hating slavery they get office. Let there be a separation, and this feeling will no longer exist, because slavery will no longer enter into the politics of the North. Does slavery in the South enter into the politics of England or France? Does slavery in Brazil or Cuba enter into the politics of the North? Not at all ; and if we were separated, the subject of slavery would not enter into the politics of the North. I say, therefore, that this remedy would be sufficient for this disease in the worst aspect of it. Once out of the Union, we would be beyond the influence of the yeas and nays of the North. Get us out, and we are safe.

BENNING CONTINUED

I think, then, that this conviction in the mind of Georgia—namely, that the only remedy for this evil is separation was well-founded. She also was convinced that separation would be the best, if not the only remedy for the fugitive slave evil and for the territorial evil. It may be asked, sir, if the personal liberty bills, if the election of Lincoln by a sectional majority, had nothing to do with the action of Georgia? Sir, they had much to do with it. These were most important facts. They indicated a deliberate purpose on the part of the North, in every case in which there was a stipulation in favor of slavery, to obliterate it if it had the power to do so. They are valuable in another respect. These personal liberty bills were unconstitutional; they were deliberate infractions of the Constitution of the United States; and being so, they give to us a right to say that we would no longer be bound by the Constitution of the United States, if we choose. The language of Webster, in his speech at Capon Springs, in your own State, was, that a bargain broken on one side, is broken on all sides. And in this opinion many others have coincided. And these Northern States having broken the Constitutional compact gives us cause to violate it also if we choose to do it. The election of Lincoln in itself is not a violation of the letter of the Constitution, though it violates it in spirit. The Constitution was formed with a view to ensure domestic peace and to establish justice among all, and this act of Lincoln’s election by a sectional majority, was calculated to disregard all these obligations, and inasmuch as the act utterly ignores our rights in the government, and in fact disfranchises us, we had a full right to take the steps that we have taken.

Now, I ask the question, Georgia feeling this conviction, what could she have done but to separate from this Union? Was she to stay and wait for Abolition? Sir, that was not to be expected of her? She did the only thing that could have been done to ensure her rights.

The second branch of my case is to lay before the Convention some facts to influence them, if possible, to accept the invitation of Georgia to join her in the formation of a Southern Confederacy.

What ought to influence a nation to enter into a treaty with another nation? It ought not be, I am free to say, any higher consideration than interest—material, social, political, religious interests. I am free to say that unless it could be made to appear that it was to her interest, she ought not to enter into it. And it shall be my endeavor now to show that it will be to the interest of Virginia materially, socially, politically and religiously, to accept the invitation of Georgia to join the Southern Confederacy—and, first, will it be to her material interests?

Georgia and the other cotton States produce four millions of bales of cotton, annually. Every one of these bales is worth $50. The whole crop, therefore, is worth $200,000,000. This crop goes on growing rapidly from year to year. The increase in the last decade was nearly 50 per cent. If the same increase should continue for the next decade we should have, in 1870, six million bales ; in 1890,This is the year cited in the Enquirer, although the speaker must have meant to say 1880. nine million of bales, and so on. And, supposing that this rate will not continue, yet we have a right to assume that the increase, in after years, will be very great, because consumption outruns production, and so long as that is the case, production will try to overtake it.

You perceive, then, that out of one article we have two hundred millions of dollars. This is surplus, and a prospect of an indefinite increase in the future. Then, we have sugar worth from fifteen to twenty millions of dollars, increasing every year at a pretty rapid rate. Then, we have rice, and naval stores, and plank, and live oak and various other articles which make a few more millions. You may set down that these States yield a surplus of $270,000,000 with a prospect of increase. These we turn into money and with that we buy manufactured goods. iron, cotton and woolen manufactures ready made and many other descriptions of goods necessary for consumption. Then we buy flour, and wheat, and bacon, and pork, and we buy mules and negroes ; very little of this money is consumed at home; we lay it out this way.

BENNING CONTINUED

Now I say, why will not Virginia furnish us these goods? Why will not she take the place now held by New England and New York, and furnish to the South these goods? Bear in mind that the manufactures consumed by the South are manufactures of the United States. They have now got the whole market by virtue of the tariff which we have laid on foreign importation. Will not Virginia take this place? I ask, is it not to the interest of Virginia and the border States to take this place? Most assuredly it is. Now I say it is at her own option whether she will take it or not. I dare say she can have the same sort of protection against the north that she has against Europe. That being so, and inasmuch as the same cause must produce the same effect, the same cause that built up manufactures at the north, will operate similarly in Virginia.

Then the question is, will you have protection necessary to accomplish this result? I say I think you will. I do not come here, as I said at the outset, to make promises; but I will give my opinion, and that is that the South will support itself by duties on imports. It has certainly begun to do that. We have merely adopted the revenue system of the United States so far, and are now collecting the revenue under an old law. Our Constitution has said that Congress should have the power to lay duties for revenue, to pay debts and to carry on the government, and therefore there is a limit to the extent that this protection can go, and within that the South can give protection that will be sufficient to enable you to compete with the North. We have got to have a navy, and an army, and we have got to make up that army speedily. It must be a much larger army than we have been accustomed to have in the late Union—it must be large in proportion to the army that it will have to meet. These things will require a revenue of about 10 per cent, which will yield an aggregate of about $20,000,000, and with this per cent, it would be in the power of Virginia to compete, in a short time, with all the nations of the earth in all the important branches of manufacture. Why? Because manufacturing has now been brought to such perfection by the invention of new machinery. The result will be the immigration of the best men of the North; skilled artizans and men of capital will come here and establish works among you. You have the advantage of longer days and shorter winters, and of being nearer to the raw material of a very important article of manufacture. I have no idea that the duties will be as low as 10 per cent. My own opinion is that we shall have as high duty as is now charged by the General Government at Washington. If that matter is regarded as important by this Convention, why the door is open for negotiation with us. We have but a provisional and temporary government so far. If it be found that Virginia requires more protection than this upon any particular article of manufacture let her come in the spirit of a sister, to our Congress and say, we want more protection upon this or that article, and she will, I have no doubt, receive it. She will be met in the most fraternal and complying spirit.

What is the state of the cotton trade? The North by virtue of their manufactures buy our cotton. They then take our cotton to Europe; they buy for it European manufactures; they take these manufactures and carry them to Boston, New York or Philadelphia, whence they distribute to us and all over the continent. But this all depends on the fact that they have manufactures to buy the cotton with. New York, Boston and Philadelphia, in fact, fatten upon the handling of cotton, and I ask why it is you do not avail yourselves of the advantages which these possess; why do you not take the place of New York, engage in manufactures, sell us your goods, take our cotton and send it to Europe for goods, and thus make this city the centre of the earth? I know that in the outset foreign imports would come direct to our ports, because you have not the manufactured goods to buy the cotton with, and we would have to send the cotton direct to Europe. But after a while you would have a monopoly of our trade having all the facilities to build up a manufacturing business extensive enough for the requirements of the whole country.

What would be the effect of this? Your villages would grow into towns, and your towns would grow into cities. Your mines would begin to be developed, and would throw their riches over the whole land ; and you would see those lands enhanced, which you have now to give away, almost, for nothing.

I say, then, it is in your power, by joining our Southern Confederacy, to become a great manufacturing empire. If you do not consider our organization as it is now made good enough, go down to Montgomery, and say, change this in such and such a form, and I venture to assert that they will meet you in the spirit in which you go. As things now stand, there is a great drain of wealth from the South to the North. The operation of the tariff, which at present averages about 20 per cent, is to enhance the prices of foreign goods upon us to that extent; and not only foreign goods, but domestic goods, as they will always preserve a strict ratio with the price charged for foreign imports. The South is thus heavily taxed. What the amount of tribute is which she pays to the North in this form, I have not accurately ascertained. It is difficult to find out how much tribute she pays in this form, but, from a rough estimate which I have made out myself, putting the amount of goods consumed by the South at $250,000,000 annually, though a Northern gentleman puts it at $300,000,000; but putting it at $250,000,000, the tribute which the South pays to the North annually, according to the present tariff [20 per cent] amounts to $50,000,000. Then there are the navigation laws which give the North a monopoly of the coasting trade. The consequence of this monopoly is that it raises freights, and to that extent enhances the price of goods upon us. There is the indirect carrying trade, in which they also have a monopoly. Instead of our goods coming to us direct, they now come by New York, Philadelphia or Boston. Last year the amount of goods that came to the South by this indirect route was about $72,000,000 which were not carried at a less cost than $5,000,000, which, of course, had to be paid by us. In the matter of expenditures we have not more than one fifth allotted to us, whereas we ought to have one-third. In 1860 the expenditures were $80,000,000, and the proportion of this which is lost to us by an unjust system of discrimination amounts to nearly $20,000,000. This is a perpetual drain upon us.

Mr. BENNING then referred to the drain in the matter of fugitive slaves, and proceeded to ask what would Virginia gain by joining the Southern Confederacy? What, said he, is the state of things now on the border? Is it such as to prevent the escape of slaves? It is not. There is a remedy for this. The state of things on the other side of the line should be such that slaves would not be induced voluntarily to run off, and if they did, that they would again soon gladly return. If you were with us, it would become necessary, in order to collect our revenue, to station police officers all along the border, and have there bodies of troops. It could be easily made part of the duty of these officers to keep strict watch along there and intercept every slave, and keep proper surveillance on all who may come within the line of particular localities. Is not that arrangement better than any fugitive slave law that you could get? Most assuredly it is. If we were separated from the North, the escape of a fugitive slave into their territory would be but the addition of one savage to the number they have already. (Laughter.)

Separate us from the North, and the North will be no attraction to the black man—no attraction to the slaves. It is not from a love for the black man that they receive him now; but it is from a hatred to slavery, and from a hatred to the owners of slaves.

Is not this a better remedy than anything that you can get out of Congress or in any form of legislation?

As regards the Territorial evil, I will show that the remedy for that too, is in separation. We want land, and have a right to it. How are we to get our share of it? Can we get it in the Union? Never. Put what you please in the Constitution, you never can get one foot of that land to which you have so just a claim. Why? Kansas tells the reason. The policy of the Black Republican party is to have this land settled up by those who do not own slaves. Their policy is the Homestead bill. You can enjoy all these things if you join us; and not only that, but you can enjoy them in peace. Cotton is peace. It is an article of indispensable necessity to the nations of the world, and they cannot obtain it without peace. Whenever there is war they cannot have it, and will therefore have peace. Join us, therefore, and you will have the advantage of enjoying all those,benefits in peace.

Suppose you join the North, what can they give you? Nothing. They will maintain, in the matter of manufactures, a competition that will destroy you. You cannot go into any market in the world and compete with them. They have the start of you, and you cannot catch up. How will it be with agricultural enterprise? Manufactures give the most active stimulant to agriculture, and when you cannot build up manufactures, you must suffer in your agricultural pursuits. Then there is the social and religious aspect of the question. Go with us, and the irrepressible conflict is at an end. We are the same in our social and religious attributes. We have a common Bible; we kneel at the same altar, break bread together, and there can be no difficulty between us on this score.

BENNING CONTINUED

Then there is the political question. Suppose you join us, and also the other border States, which they will, if you come in. We shall have a territory possessing an area of 850 or 900,000 square miles, with more advantages than any similar extent of territory on the face of the earth, lying as it is between the right parallels of latitude and longitude, having the right sort of coast facilities, and abounding in every production that can form the basis of prosperity and power.

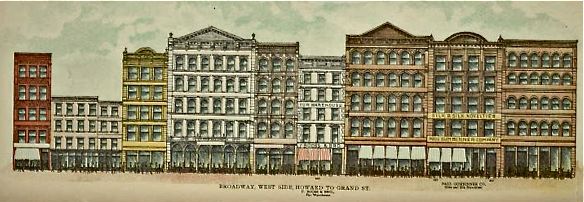

Mr. BENNING referred to the probability of the Pacific States forming a distinct Confederacy after a separation shall once occur, and then discanted briefly on the general corruption which seems to exist at the North, where men make politics a profession, requiring property to be taxed for their support. He instanced the enormous burdens amounting to nearly $2,000,000 a year, to which the city of New York is subjected through the corrupting influences of politicians, and deduced from this state of things the decay and ultimate disintegration of the North after she shall have been cut off from the rest of the Union, and circumscribed with the narrow limits of her own unproductive inhospitable area.

If, said he, you join in the Southern Confederacy, you will become the leader of it as you are now. You will have the Presidency and Vice-Presidency and other advantages which it is unnecessary here to mention.

Join the North, and what will become of you? In that, I say, you will find yourself much lower than you stand now. No doubt the North will now make fine promises, but when you are once in, they will give you but little quarter. They will hate you and your institutions as much as they do now, and treat you accordingly. Suppose they elevated Sumner to the Presidency? Suppose they elevated Fred. Douglas, your escaped slave, to the Presidency? And there are hundreds of thousands at the North who would do this for the purpose of humiliating and insulting the South. What would be your position in such an event? I say give me pestilence and famine sooner that that.

As regards the African slave trade, we have done what we could to expel the illusion which is said to deter some timid persons from uniting with us. Our State has given her voice against it, and so has Alabama, and finally the Convention at Montgomery has placed the ban upon it by a Constitutional provision. Suppose we re-open the African slave trade, what would be the result? Why, we would be soon drowned in a black pool; we would be literally overwhelmed with a black population. If you open it, where are you going to stop? There is no barrier to it but that of interest, and that will never be a barrier until there will be more slaves than we want. But go down to Montgomery and we will stipulate with you, and satisfy you, I have no doubt, upon that, as upon all other questions. What danger is there in your going with this Confederacy? You will have, with the other border States, a population of eight millions, while we will have only five. What danger is there then with such a preponderance in your favor?

I heard another objection urged to your joining us, and that is, that we held out a threat in the way of a provision in our Constitution that Congress shall have power to stop the inter-State slave trade. I do not hesitate to say to you, that in my opinion, if you do not join us but join the North, that provision would be put in force. I think that these States would do all in their power to keep the border States slave States. It would be a mere instinct of self-preservation to do that, and I think that it would be done. But is this to be regarded as a threat held out to deter you from joining the North? You might as well say that a provision in respect to a tax is a threat against you.

After meeting the objection urged against the seceding States for seceding without consultation with the border States, with the argument of necessity, he closed with an expression of thanks to the Convention, and submitted the Ordinance of Secession passed by Georgia, which was read by the Clerk.} (Reese, George H. Proceedings of the Virginia State Convention of 1861, vol. 1. Print)}

“Tomorrow is my address to the Convention I will make this (the “illusion of reconstruction”-ED) one of my main points – so will the Georgia and perhaps the Mississippi Commissioners . . . Virginia will not take sides until she is absolutely forced.” John S. Preston to (Francis W. Pickens), Feb. 17, 1861, John Smith Preston Papers, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC. as cited in Dew, pp. 60-61)

ACT II – SCENE III – JOHN SMITH PRESTON WINS HIS DAY: But when at last this mad fanaticism, this eager haste for rapine, mingling their foul purposes, engendered this fell spirit which has seized the Constitution itself in its most sacred forms and distorted it into an instrument of our instant ruin; why, then, to hesitate one moment longer seems to us not only base cowardice, but absolute fatuity.

February 19 – Tuesday, Richmond, VA: Sixth Day of the Convention

Mr. Preston, commissioner from South Carolina, addresses the Convention; he explains why his state exercised her right of secession, and urges the people of Virginia to join with South Carolina in protection of their common rights and interests.

(NOTE: Mr. Preston is careful to describe the relationship between the Federal government and States as “a compact.”-ED).

{Mr. President and Gentlemen of Virginia:

I have had the honor to present you, sir, and this Convention my credentials, as Commissioner from the Government of South Carolina, and, upon your reception of these credentials, I am instructed by my Government to lay before you the causes which induced the State of South Carolina to withdraw from the Union, and the people of South Carolina to resume the powers which they had delegated to the Government of the United States of America.

It will be recollected by all that the British Colonies of North America, save by contiguity of territory, held no nearer political Union with each other than they did with the Colonies under the same Government at remote parts of the empire. They had a common Union, and a common sovereignty in the Crown of Great Britain. But when that Union was dissolved, each colony was remitted to its own ministry as perfectly as if it was separated from the other by the oceans of the empire. But being of joint territory, and having common interests, and having identical grievances against the mother country, the people of these colonies met together, consulted with each other at various times for a long series of years, and in various forms, but, as you may remember, most generally, in the form of a Congress of independent powers. They began their conflict with the mother Government each for itself, and the battles of Lexington, of Bunker Hill, of Fort Moultrie in the colony of South Carolina, and the battle of the Great Bridge in the colony of Virginia-all occurred before their common Declaration of Independence on the 4th of July, ’76. The Colonies, then in Congress, made a joint declaration of their freedom from Great Britain, of their independence and of their sovereignty.

. . . individually, they could not carry on this contest for independence and sovereignty, they united in certain articles which are known as the Articles of Confederation. In these articles there is the reiteration of the original declaration of the sovereignty and independence of the parts of it. All rights, all powers, all jurisdiction therein delegated produce no limitation upon the ultimate and discretionary sovereignty of the parts of it.

PRESTON CONTINUED

Four years later than this, it became apparent that their alliance was not sufficient for conducting the faculties of peace as it had been for conducting the faculties of war; and the remedies for this insufficiency resulted in that instrument known as the Constitution of the United States of America, and the amendments thereto proposed by the States individually.

Now, gentlemen of Virginia, we all know that in this instrument there is no one clause, no one phrase, no one word which places the slightest limitation, or indicates the slightest transmission of the sovereignty of the parties to that compact. On the contrary, the whole spirit and genius of that instrument goes to recognize itself as a mere agency for the performance of delegated functions, and to recognize the parts of it as the original holders of the sovereignty. In proof of this, the States at various times, under various forms, with a treaty reservation, consented to this compact. Now since that period, of course there has been no legitimated change of the relations of the parts under this compact.

. . . Then, are these questions of sufficient magnitude to require the interposition of sovereignty?

. . . Gentlemen, in these relations of the States to each other and to the Federal Government, the people of South Carolina have assumed that their sovereignty has never been divided; that it has never been alienated; that it is imprescriptibly in its entire; that it has not been impaired by their voluntarily refraining from the exercise of certain functions of sovereignty which they had delegated to another power, and upon this assumption, they contend that in the exercise of this unrestricted sovereignty, and upon the great principle of the right of a sovereign people to govern themselves, even if it involves the destruction of the compact which by its vitiation has become in imminent peril, that they have a right to abrogate their consent to that compact.

PRESTON CONTINUED

. . . As preliminary to this statement, I would say, that as early as the year 1820, the manifest tendency of the legislation of the general government was to restrict the territorial expansion of the slaveholding States. That is very evident in all the contests of that period;

. . . Besides this, I would state, as preliminary, that a large portion of the revenue of the government of the United States has always been drawn from duties on imports. Now, the products that have been necessary to purchase these imports, were at one time almost exclusively, and have always mainly been the result of slave labor, and therefore the burden of the revenue duties upon imports purchased by these exports must fall upon the producer who happens also to be the consumer of the imports.

In addition to this, it may be stated, that at a very early period of the existence of this Government, the Northern people, from a variety of causes, entered upon the industries of manufacture and of commerce, but of agriculture scarcely to the extent of self support.

. . . it was important that all the sources of the revenue should be kept up to meet the increasing expenses of the Government, it also manifestly became of great importance that these articles of manufacture in which they have been engaged should be subject to the purchase of their confederates. They, therefore, invented a system of duties partial and discriminating, by which the whole burden of the revenue from this extraordinary system fell upon those who produced the articles of exports which purchased the articles of imports, and which articles of import were consumed mainly, or to a great extent, by those who produced the exports.

Now, the State of South Carolina being at the time one of the largest exporters and consumers of imports, was so oppressed by the operations of this system upon her, that she was driven to the necessity of interposing her sovereign reservation to arrest it, so far as she was concerned.

. . . It could no longer be the avowed policy of the Government to tax one section for the purpose of building up another. But so successful had been the system; to such an extent had it already, in a few years, been pushed; so vast had been its accumulations of capital; so vastly had it been diffused throughout its ramifications as seemingly to inter-weave the very life of industry itself, in the two sections into each other in the form of mechanics, of manufactures, ships, merchants, and bankers. The people of the Northern States have so crawled and crept into every crevice of our industry which they could approach, and they have themselves so conformed to it, that we ourselves began to believe that they were absolutely necessary to its vitality; and they have so fed and fattened, and grown so great and large as they feed and fatten upon this sweating giant of the South, that with the insolence natural to sudden and bloated wealth and power, they begin to believe that the giant was created only as their tributary.

Now, strange as it may seem, it is nevertheless true, that while they were thus building up their wealth and their power from these sources, step by step, we will see latterly that, with this aggregation of wealth was growing up a determined purpose to destroy the very sources from which it was drawn. I pretend not ta explain this; I refer to it merely as history.

This, gentlemen, brings me directly to the causes which I desire to lay before you. For fully thirty years or more, the people of the Northern States have assailed the institution of African slavery. They have assailed African slavery in every form in which, by our contiguity of territory and our political alliance with them, they have been permitted to approach it.

PRESTON CONTINUED

Secondly, then, in pursuance of the same purpose that I have indicated, a large majority of the States of the Confederation have refused to carry out those provisions of the Constitution which are absolutely necessary to the existence of the slave States, and many of them have stringent laws to prevent the execution of those provisions; and eight of these States have made it criminal, even in their citizens to execute these provisions of the Constitution of the United States, which, by the progress of the government, have become now necessary to the protection of an industry which furnishes to the commerce of the Republic $250,000,000 per annum, and on which the very existence of twelve millions of people depends.

. . . Now, gentlemen, the people of South Carolina, being a portion of these eight millions of people, have only to ask themselves, is existence worth the struggle? Their answer to this question, I have submitted to you in the form of their Ordinance of Secession.

Gentlemen, I see before me men who have observed all the records of human life, and many, perhaps, who have been chief actors in many of its gravest scenes, and I ask such men if in all their lore of human society they can offer an example like this? South Carolina has 300,000 whites, and 400,000 slaves. These 300,000 whites depend for their whole system of civilization on these 400,000 slaves. Twenty millions of people, with one of the strongest Governments on the face of the earth, decree the extermination of these 400,000 slaves, and then ask, is honor, is interest, is liberty, is right, is justice, is life, worth the struggle?

. . . Now, gentlemen, for one moment look at the other side of the picture. For thirty years, by labor, by protest, by prayer, by warning, by every attribute, by every energy which she could bring to bear, my State has endeavored to avert this catastrophe. For this long series of years in the federal legislature what has been her course? What has been the labor which she has performed? What has been the purpose which she has avowed? Has she not given to this all her intelligence, all her patriotism, all her virtue-and that she had intelligence; that she had patriotism; that she had virtue is in proof, because that marble sits in the hall where the sovereignty of Virginia is consulting upon the rights and honor of Virginia. (Applause.) All this she did in the Federal Government. Failing in this more than a year ago, seeing the storm impending, seeing the waves rising, she sends to this great, this strong, this wise, this illustrious Republic of Virginia, a grave commission, the purport of which, with your permission, gentlemen, I will venture to relate.

PRESTON CONTINUED

“Whereas the State of South Carolina, by her ordinance of A. D. 1852, affirmed her right to secede from the Confederacy whenever the occasion should arise, justifying her, in her own judgment, in taking that step; and in the resolution adopted by her Convention, declared that she forbore the immediate exercise of that right, from considerations of expediency only:

And, whereas, more than seven years have elapsed since that Convention adjourned, and in the intervening time, the assaults upon the institution of slavery, and upon the rights and equality of the Southern States, have unceasingly continued with increasing violence, and in new and more alarming forms be it therefore,

- Resolved unanimously, That the State of South Carolina, still deferring to her Southern sisters, nevertheless respectfully announces to them, that it is the deliberate judgment of this General Assembly that the slaveholding States should immediately meet together to concert measures for united action.

- Resolved unanimously, That the foregoing preamble and resolution be communicated by the Governor to all the slaveholding States, with the earnest request of this State that they will appoint deputies, and adopt such measures as in their judgment will promote the said meeting.

- Resolved unanimously, That a special commissioner be appointed by his Excellency the Governor to communicate the foregoing preamble and resolutions to the State of Virginia, and to express to the authorities of that State the cordial sympathy of the people of South Carolina with the people of Virginia, and their earnest desire to unite with them in measures of common defence.”

This, gentlemen, was one year ago and no more. Failing in that effort, the people of South Carolina, for the first time in over 20 years, joined with the political organizations of the day, in the hopes-of deferring the catastrophe.

. . . After this simple act of excision still she has not been satisfied, and now still she is seeking aid, she is seeking counsel, she is seeking sympathy, and, therefore, gentlemen, I am before you here today. Now, gentlemen of Virginia, notwithstanding these facts which I have so feebly grouped before you, notwithstanding this patience which I have endeavored to show you she has practised, my State, throughout this whole land, throughout all Christendom, my State has been charged with rash precipitancy. Is it rash precipitancy to step out of the pathway when you hear the thunder crash of the falling clouds? Is it rash precipitancy to seek for shelter when you hear the gushing of the coming tempest, and see the storm cloud coming down upon you? Is it rash precipitancy to raise your hands to protect your head? (Loud applause.)