by Jim Surkamp on May 16, 2018 in Jefferson County

Made possible with the generous, community-minded support of American Public University System (apus.edu). CivilWarScholars.com is intended to promote understanding and learning of the past upon which is based our present-day, but content is not in any way a reflection of the 21st century modern-day policies of the University.

I’d like to call your attention and fuel your imagination to a day in August in 1855. I want to direct you on where we’re going rather than where we’re starting. The reason for picking August is – by that time the fresh grain, wheat especially – would be coming off and been harvested. You would have harvested the wheat

by taking what is known as a scythe and cradle and cutting it.

Someone else would come along behind you and bundle it up into sheaves. Then another couple of people would come along behind you with forks and throw them onto wagons pulled by horses and take it off to be threshed.

The farmers – as they would harvest the wheat – they would all get together, their hands, and if they had those enslaved they used them. They started at farmer X, did his wheat; they moved to farmer Y, did his wheat. When lunchtime came, the ladies from the neighborhood came to whichever farm you were harvesting and they cooked dinner. I was fortunate enough to sit in on a couple of those thresherman’s dinners as I was a pre-schooler. But it was the fellowship, the jokes and all, the aggravation and the foibles and such.

FOR DECADES, JEFFERSON AND LOUDOUN COUNTIES WERE A FINE FLOUR EMPIRE THAT FED CONTINENTS. AFTER THE CIVIL WAR, SOME COUNTY FARMERS, THEIR WHEAT FIELDS SEVERELY IMPACTED BY YEARS OF ARMIES, HORSES, MEN AND WAGONS, NECESSARILY PUT THEIR LANDS TO A NEW USE – APPLE ORCHARDS, ESPECIALLY THOSE FARMS LOCATED ALONG RAILROAD LINES.

WROTE OBSERVER NICHOLAS CRESSWELL AS FAR BACK AS 1774:

Thursday November 24th, 1774 Great quantities of wheat are brought down from the back Country in waggons to this place, as good Wheat as ever I saw in England. It is sent to Eastern markets. Great quantities of Flour are likewise brought from there, but this is generally sent to the West Indies and sometimes to Lisbon and up the Streights.

SHARPENING THE “BLADES” FOR MILLING THE GRAIN:

STARTING THE MILLING:

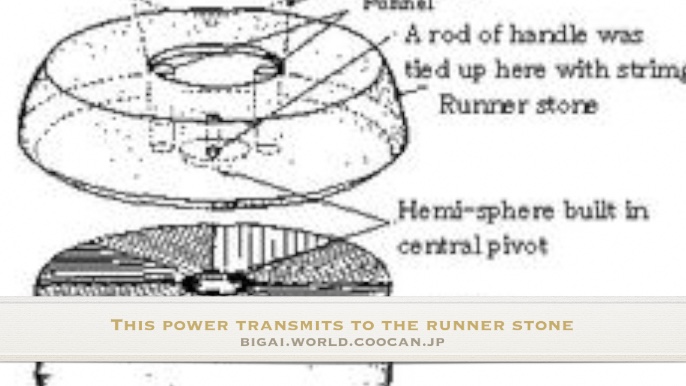

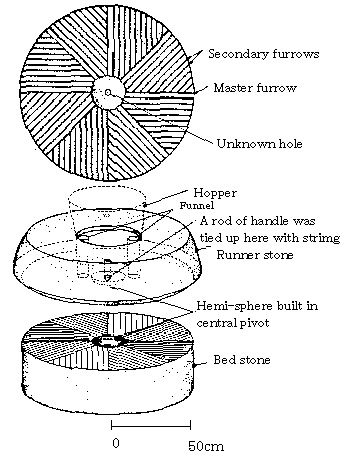

Grains funnel down the hole to the center of the typically 1,200 pound runner stone that is spinning, maybe 120 revolutions per minute, pressing and crushing the mass of grain but never touching the stationary bottom stone.

>

The markets for local flour in Danny’s younger days in the 1950s had for several decades been eroded by wheat and flour production in the Midwest, especially after the introduction of superior large-scale milling equipment there and the fact that long distance freight on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was priced at less per mile than the fares for local shorter freight routes.

THE CENTURY OF GLORIOUS WHEAT WAS CHARACTERIZED THIS WAY:

Always a breadbasket but Jefferson County was no longer a great force in fine flour production, like in the days when flour from Feagan’s mill went by wagon to Harper’s Ferry and, when there, put either on canal boats bound for port in Alexandria, Va. or on rail freight cars bound for Baltimore – and from both these ports to lucrative markets on the far side of vast oceans.

But coming to the mill, the wagon would offload the milk first to keep it cool. Off to the side, they dumped the wheat through one of the ports to go into the hopper to the elevators to go into the burrs to be ground, sacked and put back on the wagon at the dock. And this could take a better part of a day, because it was on a first-come, first-serve basis and you waited your turn and sat around. I’m certain they probably had a jug of certain spirits under the seat or on the buckboard on the wagon, whatever they were using to haul the grain and the milk. And they probably shared it. And if there was enough of it to go around, it might have even affected the cost of milling the grain. But I can’t say that for certain.

Most likely you would have had fresh milk and fresh cream. They put several 25-gallon milk cans – metal cans – of milk unseparated and go off to the Haines mill. The reason for taking the milk was because there was also a creamery there. So not only would you be getting your milk churned – the cream separated and churned into butter and butter milk and such – and you’d be meeting the rest of the neighbors and getting caught up on the latest gossip which you hadn’t heard about in the field.

DANNY REFLECTS ON CHANGE IN THE FIELD OF LIFE:

Now we’ve gotten the grain ground and we’re getting ready to leave Feagan’s Mill after a day of chatter and work and everything else.

But we’ve got one more stop we’ve gotta make with the horses and wagon because we have fleeces on the wagon from the shearing of the sheep. That’s a job in and of itself with the hand shears and all that, but that’s another story. Right down the road on our way home is the Job’s woolen mill, woolen factory. So we make a stop there. Like Feagan’s Mill it’s pretty busy. People don’t gather there as much as people at the grist mills. You leave your fleece off, come back later on after it’s been cleaned, carded, spun and woven into the blankets or bolts of cloth whatever. And you pick it up later on and go home. So we gotta drop the fleeces off. After we’ve done that we’re ready to go home.

Something about the threshing of the grain, as I mentioned before, harvesting the grains on the farms in Jefferson County, like most communities around the country, was a community affair. Everyone else helped everyone else. All the other farmers in the area helped Farmer X harvest his and the threshing crews worked up the road (to) farm after farm and their hired help and in the case of those who had those enslaved, the enslaved were involved in it as well. When mealtime came, all the threshing help, all the field help went into the main house where the ladies from the neighborhood – all the farm ladies and their daughters had prepared lunch. And it was nothing to sneeze at. If you went away hungry it was your own fault. Now the white threshermen and field hands ate at the main dining table in either the kitchen, which were huge in many of those houses or the main dining room. The black help ate on the back porch or on the outside. Now I was involved in the days that the combination harvesters/threshers called combines were coming into vogue. But I still remember a few of these neighborhood threshings. I remember going to – as my mother was helping with the lunch preparation – and like the day I described in 1855, this goes up to 1955 that the white help went into the main house and ate dinner at the main dining table and the black help had their dinner on the back porch. Well, now you’ve heard it said that little children are supposed to be seen and not heard. These ladies made sure we understood that. It wasn’t very long before I learned that it was far more interesting to be on the back porch with the black help having lunch than in the main dining room with the white help. And they had stories to tell and jokes to tell and such and it was amusing. And they also had their music. These fellas would jive with each others with what I came to know were called “race records.” That is black music, recorded music whose lyrics were too earthy for white audiences. The difficulty came when I started to mimic these songs and parodies. This did not go over well with the ladies at all and I ended getting persuaded on the back of my pants that this was not the thing to do. I still haven’t forgotten some of those lyrics, but they’re kind of interesting – which all goes to the day I really became aware of the difference between black and white. My sister was taking dancing lessons and because my mother couldn’t pick us up that particular afternoon, my grandfather did. On the way home in his Dodge pickup – single-seat truck, unlike these multi-cab jobs that we now have. We were never supposed to have more than three people in the cab of the truck, but (they) looked the other way. On the way out 340 right there on the edge of town near the Perry Farm, a black man was hitch-hikding in a driving rainstorm. Granddad knew him and he stopped. My sister and I were gonna slide over to make room for him in the cab. Granddad said: “No, just get on the back.” And as he got on the back, Granddad pulled away in the truck, he looks at us and said: “No sense crowdin that ni**er in with us.” Now, even at seven years old,

I realized it was just as wet back there for him as it was (earlier) for us, and though it would have been crowded, four of us could have sat in that cab without any problem. And, yet why was this being done? And there was no explanation.

References:

1. Douglas W. Kent-Jones R. Paul Singh. “Cereal Processing.” britannica.com 23 May 1998 Web. 7 May 2018.

2. Kiran Yadav. “Methods of Sowing: Wheat.” agropedia.iitk.ac.in 17 September 2008 Web. 7 May 2018.

3. THE IOWA AGRICULTURIST

For the Farm, Garden & Household

“Throughout the early 1800’s inventors worked to improve methods and machinery for planting small grain crops. By the 1860’s the grain drill was widely used by farmers in the eastern states. The grain drill didn’t come into common use in Iowa until after 1870. There were many types of drills that were invented and manufactured. Generally, the grain drill was pulled by horses and allowed a space for a rider. A grain box was used to hold a supply of seeds to be planted. The planting mechanism included tubes through which the grain fell into furrows made by discs or shoes attached to the bottom of the drill. – Malcolm Price Laboratory School, University Of Northern Iowa

iowahist.uni.edu 7 January 2018 Web. 7 May 2018.

4. Wright, Robert P. “Principles of Agriculture.” London: Blackie & son. p. 44.

books.google.com 24 November 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

5. Agricultural History Series. Missouri State University, Post Civil War Farm Equipment, Planters and Drills – 1865 – 1872

lyndonirwin.com 1 February 2001 Web. 10 May 2018.

Threshing Through Time:

6. Jefferson County Assessor’s Office, Charles Town, WV – confirmation of owners of Feagan’s Mill complex.

7. Mill complex

wikipedia.org 27 July 2001 Web 7 May 2018.

8. Shocking Wheat by Dennis Warden

Published on Jul 15, 2010

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

9. Using A Grain Cradle

by Genetta Seeligman. Photographs by Stephen Hough. Interview by Ronnie Hough, Genetta Seeligman. “Using a Grain Cradle.” Bittersweet Volume I, No. 3. spring, 1974:

“To shock the grain he sets the tied bundles upright against each other with the grain end up. He starts with two bundles leaning together to form the nucleus. Other bundles are added around these, two at a time opposite each other to balance the shock. Depending on the grain, how long it is, and its weight, he sets six to eight upright. If the bundles are small, he would use eight or even ten to a shock. The bundles would have to stay usually a few weeks to cure and wait for the threshing machine, so the shock would need to be capped to keep the grain dry. He spreads out one bundle as much as possible without untying and lays it one way across the tops of the upright bundles. This makes an effective “roof” to shed the water. “You put another bundle on top of that and it’ll stay there until September or October. I’ve seen them haul them out way up in October. But they’re better the quicker you can thrash them after they get cured. You see, you got a double cap there, and it won’t rain in to it. The wind don’t blow them off and tear it up, why it’s there.”

thelibrary.org 30 June 2007 Web. 7 May 2018.

10. Stook – Wikipedia

A stook, also referred to as a shock or stack, is an arrangement of sheaves of cut grain-stalks placed so as to keep the grain-heads off the ground while still in the field and prior to collection for threshing. Stooked grain sheaves are typically wheat, barley and oats.

wikipedia.org 27 July 2001 Web 7 May 2018.

11. Threshing with hand flails – two people threshing

Sounds of Changes

Published on Dec 29, 2014

A hand flail is a simple tool for threshing cereal grain. Sheaves of grain are laid on a wooden floor in two parallel lines so that the ears of both lines face into the centre. The threshers work in pairs (one or two pairs) and in equal intervals alternately beat the ears with the flails.

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

12. Stahl, John M. (January, 1893). “Threshing on the Prairie.” The American Agriculturist, Volume 52. New York: Orange Judd Company. books.google.com 24 November 2005 Web. 7 May 2018. p. 394.

Twenty years ago practically all the small grain in the West was stacked; there were few mows, and very little was threshed from the shock. Now a very large part is threshed from the shock, this being the general rule in the most progressive localities. The farmers have for years tried threshing from the shock, and general experience has demonstrated that this is superior to stacking the grain. Grain in stacks is not infrequently damaged. The stack may be improperly built, or it may be wrecked by a storm, or the season may be so wet and warm that before the grain can be threshed some of it will sprout in even a well-built stack ; and the difficulty of getting good stackers has constantly increased. On the other hand, some of the reasons for stacking have been removed. When the threshing machines were operated by horse power, and the straw was handled along the stack altogether with forks, it was quite an advantage to put off the threshing until cool weather. But now, with steam engines and straw stackers, the work can be done in July and August without injury to man or beast. Other improvements in threshing machinery besides the automatic stacker have made it possible to do the work so rapidly that it can be got out of the way of the fall seeding. It is easier to put the grain on the thresher’s table than on the stack ; and all the hard labor of stacking and of pitching the grain from the stack to the thresher’s table, is saved.

So great is the saving in handling the grain that it is by no means certain that it is not better to thresh from the shock than to mow the sheaves. To maintain mows as well as to construct them, costs money. The opinion entertained until a few years ago that to have first quality grain it must be allowed to sweat in the stack or mow, has been proved erroneous. Threshing from the shock is prudent and advisable only when the work is done promptly. If it is much delayed, rains may interfere and the grain will sprout in the shock. But the man who intends threshing from the shock should make his arrangements early.

13. Threshing Video Slate Run Farm

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

14. Butterworth, Benjamin. (1892) “The growth of industrial art.” Patent Office. Washington, D.C.: Govt. print. off. Print.

Butterworth, Benjamin. (1892) “The growth of industrial art.” Internet Archives. archive.org 26 January 1997 Web. 9 May 2018.

p. 23 – Thrashing and Cleaning Grain

15. Jefferson County, West Virginia – 212 sq. miles 517,000 bushels of wheat in 1840.

wikipedia.org 27 July 2001 Web 7 May 2018.

16. Cresswell, Nicholas. “The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell 1774-1777.” New York, NY: The Dial Press.

books.google.com 24 November 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

Thursday November 24th, 1774 Great quantities of wheat are brought down from the back Country in waggons to this place, as good Wheat as ever I saw in England. It is sent to Eastern markets. Great quantities of Flour are likewise brought from there, but this is generally sent to the West Indies and sometimes to Lisbon and up the Streights.

p. C-47.

Mills:

17. Millstone Dressing at George Washington’s Gristmill

George Washington’s Mount Vernon

Published on Dec 15, 2015

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

Rob Grassi:

1:37:

I’ve recut the pattern back in the stones. That pattern is called the millstone dress pattern. It’s really imperative to have a millstone dress pattern because it grinds and shears that grain and moves it out when it’s working.

2:03:

The grain flows in through the topstone. It’s caught between the top and bottom millstone. drawn in by these grooves we call furrows and the grain works its way around gradually getting finer and finer till it exits the stones as finished flour.

2:35:

These millstones don’t touch each other. That’s very, very critical, but they do wear down as a result of the friction of the grinding process. I lift and drop the tool and cut the pattern back in the stone.

3:50 – 4:32: The pattern is divided into two portions. We have the deeper grooves that are called furrows, and between these furrows we have flat surfaces we call lands. That’s where all the fine flouring happens right along these lands.

18. Grinding Grain into Flour at the Old Stone Mill

Ken Watson – Published on Oct 21, 2011

Grinding Red Fife wheat into flour using 200 year old millstones at the Old Stone Mill, Delta, Ontario with Miller Moel Benoit.

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

19. Union Mills Grist Mill by Handcraftedtradition

Published on Apr 26, 2010. Milling flour at the Union Mills Maryland 1797 gristmill using 200 year-old quartz millstones.

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

:33 – opening the dam and direct water to the water wheel

1:24 – released water powers the water wheel that powers the runner stone

1:53 – fx poured grist from a sack

5:56 – sifter being shaken

20. 19th Century Technology at a Grist Mill

ScienceOnline Published on Sep 4, 2015

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

5:44 – two sets of control wheels are mounted close to the stones. The small wheel adjusts the distance between the two stones.

21. From Werner L. Janney and Asa Moore, editors, John Jay Janney’s Virginia: An American Farm Lad’s Life in the Early 19th Century (McLean, Va.: EPM Publications Inc., 1978), 72-75.

“A mill is a building equipped with machinery that processes a raw material such as grain, wood, or fiber into a product such as flour, lumber, or fabric. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Virginia’s mills were powered by water in creeks or rivers. In a flour mill, water flowing over the mill wheel was converted by gears into the power to turn one of two burr stones. Kernels of wheat were then ground between the two stones. The grinding removed bran (the outer husk) from the wheat kernel, and then crushed the inner kernel into flour. Flour mills were an important part of rural communities across the country, including Waterford in the fertile Loudoun Valley of Virginia.”

In the 1700s, oxen took the flour to market in Alexandria. By 1826, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad were in operation through nearby Point of Rocks, Maryland. Waterford flour could be hauled there by oxen, then barged to Georgetown or taken by railcar to Baltimore. After the Civil War ended in 1865, and Loudoun’s damaged Washington and Old Dominion railroad could be repaired and extended west beyond Leesburg, it was even easier for Waterford area farmers to get their flour to market.

loudounhistory.org 2 November 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

22. Howe, Henry. (1852). “Historical Collections of Virginia.” Charleston, S.C.: Wm. R. Babcock. Print.

Howe, Henry. (1852). “Historical Collections of Virginia.” Internet Archives. 26 January 1997 Web. 9 May 2018.

pp. 161-162 – chart shows production in thousands of bushels annually.

23. Gear

wikipedia.org 27 July 2001 Web 7 May 2018.

24. Grist

wikipedia.org 27 July 2001 Web 7 May 2018.

Grist is grain that has been separated from its chaff in preparation for grinding. It can also mean grain that has been ground at a gristmill. Its etymology derives from the verb grind. Grist can be ground into meal or flour, depending on how coarsely it is ground. Maize made into grist is called grits when it is coarse.

Image Credits:

1. wheat grain

britannica.com 23 May 1998 Web. 7 May 2018.

2. Danny Lutz by Jim Surkamp.

3. Barn Interior by Harrison Bird Brown – circa 1885

the-athenaeum.org 23 May 2002 Web. 7 May 2018.

4. The Sower by Jean-François Millet 1850

mfa.org 20 December 1996 Web. 7 May 2018.

5. “Buckeye” Grain Drill and Grass Seed Sower – Got its name from being manufactured in the state of Ohio. Was well known and very popular in every grain growing state in 1865. A seed broadcaster could also be attached to the back of the machine to spread cover crop grasses on the ground between the drilled rows. The buckeye promised and delivered in giving wheat growers in Missouri better grain and hay yields. This was accomplished by the drill being more accurate in seeding rates and putting seed into a furrow which gave more seed to soil contact and thus aided in germination and made for better stands of crop compared to hand sowing seeds.

Agricultural History Series

Missouri State University

Post Civil War Farm Equipment

Planters and Drills – 1865 – 1872

lyndonirwin.com Start date unavailable

6. Cradle scythe – mdah.ms.gov 29 June 2016 Web. 10 May 2018.

7. The Veteran in a New Field by Winslow Homer – 1865

the-athenaeum.org 23 May 2002 Web. 7 May 2018.

8. The Wheatfield by John Constable – 1816

the-athenaeum.org 23 May 2002 Web. 7 May 2018.

9. Three Figures Gathering Wheat by William Collins

the-athenaeum.org 23 May 2002 Web. 7 May 2018.

10. Gathering Wheat by Daniel Ridgway Knight

the-athenaeum.org 23 May 2002 Web. 7 May 2018.

11. Claude Monet Wheatstacks (end of summer)

wikipedia.org 27 July 2001 Web 7 May 2018.

12. Title: Culpepper [i.e., Culpeper], Va.–Stacking wheat / E.F.

Summary: African Americans stacking wheat near Culpeper Courthouse, Va.

Contributor Names: Forbes, Edwin, 1839-1895, artist

Created / Published: 1863 Sept. 26.

loc.gov 16 June 1997 Web. 7 May 2018.

13. Bank barn at Prato Rio, Leetown, WV home of Gen. Charles Lee in the Revolution

Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey,

loc.gov 16 June 1997 Web. 7 May 2018.

14. Barn Scene by Wesley E. Webber

the-athenaeum.org 23 May 2002 Web. 7 May 2018.

15. Barn Swallows by Eastman Johnson – 1878

the-athenaeum.org 23 May 2002 Web. 7 May 2018.

16. men flailing wheat to separate chaff from the grain on a barn floor

wikipedia.org 27 July 2001 Web 7 May 2018.

17. Cover The American Agriculturist January, 1893

books.google.com 24 November 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

18. Title Farmers Nooning by William Sidney Mount – 1836

the-athenaeum.org 23 May 2002 Web. 7 May 2018.

19. Sheaves of wheat at Slate Run Farm Central Ohio Parks System

metroparks.net 21 June 2000 Web 8 May 2018.

20. Sheaves in a Field by Vincent Van Gogh the-atheneaum.org

the-athenaeum.org 23 May 2002 Web. 7 May 2018.

21. Wheat – With a threshing machine Slate Run Farm

metroparks.net 21 June 2000 Web 8 May 2018.

22. The thresher separates the plant and chaff at Slate Run Farm

metroparks.net 21 June 2000 Web 8 May 2018.

23. Wheat is guided into the threshing machine

metroparks.net 21 June 2000 Web 8 May 2018.

24. John Stahl quote The American Agriculturist

books.google.com 24 November 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

25. John Stahl quote (2) The American Agriculturist

books.google.com 24 November 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

26. John Stahl quote (3) The American Agriculturist

books.google.com 24 November 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

27. Title The separated wheat grain after threshing Slate Run Farm

metroparks.net 21 June 2000 Web 8 May 2018.

Milling:

28. Title millstone millstones.com 6 December 1998 Web. 14 May 2018.

29. Title by re-cutting the grooves

mountvernon.org 2 November 2005 Web. 10 May 2018.

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

3:38 – I lift and drop the tool and cut the pattern back in the stones.

30. Title called “furrows”

mountvernon.org 2 November 2005 Web. 10 May 2018

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

31. Title “and lands”

mountvernon.org 2 November 2005 Web. 10 May 2018

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

32. Title raised stitching

mountvernon.org 2 November 2005 Web. 10 May 2018

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

33. Title Riding the Century of Glorious Wheat

pawv.org 7 February 2002 Web. 10 May 2018.

34. Nicholas Cresswell

americainclass.org 7 October 2011 Web. 10 May 2018.

35. Henry Howe’s chart of wheat production

Howe, Henry. (1852). “Historical Collections of Virginia.” Internet Archives. archive.org 26 January 1997 Web. 9 May 2018.

pp. 161-162 – show production in thousands of bushels annually

36. Title Feagan’s Mill-1 Google Maps (Series)

google.com/maps13 July 2001 Web. 10 May 2018.

37. Feagans-2 Google Maps google.com/maps 13 July 2001 Web. 10 May 2018.

38. Feagans-3 Google Maps google.com/maps 13 July 2001 Web. 10 May 2018.

39. Feagans-4 Google Maps google.com/maps 13 July 2001 Web. 10 May 2018.

40. 19th Century Technology at a Grist Mill by ScienceOnline

Published on Sep 4, 2015

8:06 – sacks of wheat in a wheelbarrow (fair use)

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

41. Bank barn with view of lower level granary The American Agriculturist 1870 as appeared in Rawsom, Richard (1979). “Old Barn Plans.” New York, N.Y.: Mayflower Books. Inc.” p. 54.

42. Man opening the dam at Union Mills Grist Mill (matte)

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

43. Opening the dam Union Mills Grist Mill

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

44. Mill wheel with water Union Mills Grist Mill

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

45. From larger into smaller diameter cog wheels, increasing torque.(1) by Jim Surkamp.

46. From larger into smaller diameter cog wheels, increasing torque.(2) by Jim Surkamp.

47. The power that transmits to the runner stone bigai.world.coocan.jp 20 December 2007 Web. 14 May 2018.

48. Grist is poured into the hopper Moel Benoit Miller at Old Stone Mill youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

49. Moel Benoit Miller at Old Stone Mill funneling it down a hole youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

50. The runner stone to the center of the typically 1,200 pound runner stone that is spinning, maybe 120 revolutions per minute. bigai.world.coocan.jp 20 December 2007 Web. 14 May 2018.

51. The miller’s most important skill is Old Stone Mill

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

52. The closer they are with only the grains in between, the finer the flour it’s making. Moel Benoit Miller at Old Stone Mill youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

53. This wheel sets the distance 19th Century Technology at a Grist Mill ScienceOnline youtube.com.

54. The many grains vibrate their way along the cut furrows and along the lands millstones.com 6 December 1998 Web. 14 May 2018.

55. Finally to the outer periphery of the millstones. millstones.com 6 December 1998 Web. 14 May 2018.

56. And, there, the flour is examined for quality Moel Benoit Miller at Old Stone Mill youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

57. TITLE Using a sifter and a bolter, bran and unwanted debris are separated out.

58. Sifter Union Mills Grist Mill by Handcraftedtradition youtube 5:56

youtube.com 28 April 2005 Web. 7 May 2018.

59. Bolter does final separation out of finest flour particles

lousweb.com 25 March 2004 Web. 14 May 2018.

60. Montage – Wheat falls into the bolter at one end and gravity pulls it through its mechanical rotating cylindrical sieve and grain separator. Finer ground flour falls into a mesh and is carried away and down a chute for sacking.

A “Bolter” is a mechanical cylindrical sieve. Grain was fed into this device at one end and fell onto a hexagonal rotating sieve, usually made of fine screening or silk. As the grain entered it was tumbled down the rotating sieve which was tilted at a slight angle. Gravity would pull the grain through as it rotated. This is the general operating principal of all rotating “Bolters” or sieve separators. Finely ground flour particles would fall through the mesh and into a channel, where it was moved away from the apparatus through a horizontal auger channel to the far end, and dropped into a small rectangular vertical chute. The remaining larger particles would pass down and out into a separate diagonal chute.

lousweb.com 25 March 2004 Web. 14 May 2018.

61. Finest flour poured into dry barrels mountvenon.org 2 November 2005 Web. 10 May 2018.

62. Drawing These barrels in the 1800s farmer leaving home in a wagon – Jim Surkamp

63. Drawing would head for distant lands dockside negotiation – Jim Surkamp

64. Over vast oceans Google Earth Pro (1)

65. Over vast oceans Google Earth Pro (2)

66. Over vast oceans Google Earth Pro (3)

67. Daniel Haines Mill Map 1852 1 loc.gov 16 June 1997 Web. 7 May 2018.

68. Daniel Haines Mill Map 1852 2 loc.gov 16 June 1997 Web. 7 May 2018.

69. Daniel Haines Mill Map 1852 3 loc.gov 16 June 1997 Web. 7 May 2018.

70. Daniel Haines Mill Map 1852 4 loc.gov 16 June 1997 Web. 7 May 2018.

71. Scene of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal at Harpers Ferry by George Harvey the-athenaeum.org 23 May 2002 Web. 7 May 2018.

72. Baltimore Harbor

Fitz Henry Lane – 1850

the-athenaeum.org 23 May 2002 Web. 7 May 2018.

73. OR

74. Scene of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia by George Harvey – circa 1837

the-athenaeum.org 3 May 2012 Web. 9 May 2018.

75. C&O Canal Boat

nps.gov 13 April 1997 Web. 14 May 2018.

civilwarscholars.com 9 June 2011 Web. 14 May 2018.

76. Map Chesapeake & Ohio Canal

civilwarscholars.com 9 June 2011 Web. 14 May 2018.

77. The Port City

alexandriava.gov 17 March 2004 Web. 14 May 2018.

78. The Ellen Brooks Homeward Bound for New Orleans by Samuel Walters – Date unknown

the-athenaeum.org 3 May 2012 Web. 9 May 2018.

79. TITLE Danny Lutz reminisces a little more about his historic mill, evoking images of the past and shares memories of the 1950s – good and bad – including threshermen’s suppers.

80. 1868 Harper’s Weekly hand colored wood engraving titled, “Washing and Shearing Sheep in the Country.” Sketched by Edwin Forbes.

81. young boy in silhouette wearing a baseball cap

elconfidencial.com 4 April 2001 Web. 14 May 2018