Deutsch: Das Auge eines indischen Elefanten im Elephant Nature Park, Thailand

Date 9 November 2008 Source Own work Author Alexander Klink

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elephas_Maximus_Eye_Closeup.jpg

2,221 words

https://archive.org/details/battlesleadersof04cent/page/552/mode/2up?view=theater

18-year-old Private D. Wilson Arnett could no longer hear a thing in his left ear, burst in the awe-inspiring explosion of 8,000 pounds of gunpowder that in the wee hours of July 30, 1864 in front of Petersburg heaved horses, men and 400,000 cubic feet of earth into the air. The Federals planted the dynamite underground at the end of a tunnel they dug in secret and it blew a swath in the Confederate line. From that moment on and into old age, Arnett could only hear a bit in his right ear, not at all in his left ear – only of faint shouted orders, conversation, the birds and life in general. It mattered.

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/new-market-heights-september-29-1864

The day before, Private Arnett’s 5th U.S. Colored Troops led . . .

Civil War Preservation Trust

TITLE: September 29, 1864 – The Battle on Chaffin’s Farm

Fourteen men of color are awarded the highest honor – the Congressional Medal of Honor for their extreme, individual decisions of great bravery.

Civil War historian James Price writes:

“Thursday, September 29, 1864 is arguably one of the most important days in American history. Without question, it is certainly one of the most (if not THE most important day in African-American military history.” – Price, James S. (2011). ”The Battle of New Market: Freedom Will Be Theirs By The Sword.” Charleston SC: The History Press, Inc. p. 9 first paragraph in the Preface.

He goes on to say that the fighting Arnett bore with others “broke the outer ring of defenses” protecting the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia.

Arnett’s 5th U.S. Colored Troops infantry regiment had been given the heavy honor to lead an assault of 1,300 men – leading two other regiments: the 36th and 38th U.S. Colored Troops infantry regiments –

on a fortified position of seasoned Confederate Texans and Virginia artillerymen. The assault across an open field, part pine forest, part swamp, part ravine riddled with defensive abatis that needed to be breached – would come around 7:30 AM.

You could see dead and wounded on the field from an earlier failed assault by another.

Gen. Duncan’s 1st Brigade,

also in Gen. Paine’s Division to their right. Pvt. Arnett had to hear and follow any orders crossing that no man’s land –

be it from the 5th’s Lt. Colonel Giles Shurtleff,

Company I’s commander Ulysses Marvin

or from his First Sergeant Robert Pinn.

“Remember Fort Pillow and No quarter!!” exhorted their Major General Ben Butler, who commanded the overall Army of the River James, – the wholesale massacre of surrendering black Federal troops in that spring in Tennessee of which not a soldier listening that morning in that trench needed the slightest reminding.

During the tense wait, sipping his coffee as the dawn came, Arnett perhaps thought how he came to this hinge-point in history: being born in October 28, 1846 in Martinsburg, serving as a teen coachman for Charles J. Faulkner Sr., one time Minister to France and a congressman at another, at Faulkner’s Boydville mansion.

May, 1862 saw Federal General Nathaniel Banks Army fleeing Confederate General Stonewall Jackson’s men northward through Martinsburg heading north – literally, for some – to the Promised Lands,

very likely when Arnett got his chance to abscond, winding up in Akron, Ohio where, married to one Maria Louisa of Jefferson County.

He took a job as a waiter to help pay their bills. He himself would enlist during that time near Akron August 28, 1863.

Their cups of coffee emptied, Lt. Colonel Giles Shurtleff rose and said to them all: “If you are brave soldiers, the stigma — denying you full and equal rights of citizenship shall be swept away and your race forever rescued from the cruel prejudice and oppression which have been upon you from the foundation of the government.” (Price, p. 70)

TITLE: 7:30 AM Deep Bottom Camp –

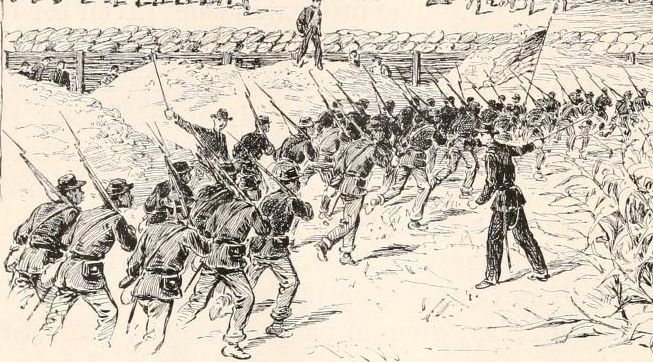

To Shurtleff’s order the 1300 men rose and stepped out on to no man’s land, stacked in a single column — feet wide 800 yards ahead were the dug in Texas sharpshooters and artillery.

The 5th led them easily at first out of the sharp-shooters range. They clambered through the first abatis of fallen trees, some using axes to remove it. Closer to the Confederate earthworks fire picked up then became a storm of blood letting men falling right and left in front. Shurtleff went down, Co. I’s Marvin was wounded also — officer in all, leaving all those units without officers to lead.

The 5th led the others forward hacking through a second abatis of trees then found themselves raked with gunfire and in a marshy ravine, slightly to the left in a ravine. The slaughter was terrific as blue coats climbed up the wall of the ravine closest to the Confederates earthworks.

J. D. Pickens of the Texas Brigade acknowledged the fighting qualities of their attackers, writing, ‘I want to say in this connection that, in my opinion, no troops up to that time had fought us with more bravery than did those Negroes.’

Brigade commander Alonzo Draper who was also wounded and the only one able to furnish an official report wrote of the carnage of the white officers:

Lieut. Col. G. W. Shurtleff, Fifth U. S. Colored Troops, though repeatedly wounded, still strove to lead his regiment; First Lieut. Edwin C. Gaskill, Thirty-sixth U. S. Colored Troops, rushed in front of his regiment, and, waving his sword, called on the men to follow. At this moment he was shot through the arm, within twenty yards of the enemy’s works; First Lieut. Richard F. Andrews, Thirty-sixth U. S. Colored Troops, had been two months sick with fever and was excused from duty. He volunteered, being scarcely able to walk. He rode to the thicket, dismounted, and charged to the swamp, where he was shot through the leg; First Lieut. James B. Backup, Thirty-sixth U. S. Colored Troops, excused from duty for lameness, one leg being partially shrunk so that he could walk but short distances, volunteered, hobbled in as far as the swamp, and was shot through the breast; Lieutenant Bancroft, Thirty-eighth U. S. Colored Troops, was shot in the hip at the swamp. He crawled forward on his hands and knees, waving his sword and calling on the men to follow. When the brigade was making its final charge, a rebel officer leaped upon the parapet, waved his sword amid shouting, “Hurrah, my brave men.” Private James Gardiner, Company I, Thirty-sixth U. S. Colored Troops, rushed in advance of the brigade, shot him, and then ran the bayonet through his body to the muzzle.

Gen. John Gregg’s Texas Brigade had urgent orders to abandon the defense of New Market Heights and hurry towards Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy just a few miles away to help defend the attacked and under-manned Fort Gilmer.

The erroneous racist-tainted deduction went: “We killed or wounded almost all the white leaders of the black men. Thus, they are defeated because the black men don’t know how to fight and win on their own. They will panic and run for the camp back at Deep Bottom.”

Instead, the black first sergeants in four companies of the 5th, including Arnett’s Company I rose like lions, seized their colors from the fallen, bared bayonets and swooped down upon the earthworks, crashed through sending the Confederates scattering far and wide.

Powhatan Beatty of Co. G left his men who retreated back to the first abatis rose ran forward in a hail of gun fire to retrieve their colors, returned to his men and charged forward. towards the enemy.

Of Company G’s eight officers and eighty-three enlisted men who entered the battle, only sixteen enlisted men, including Beaty, survived the attack unwounded. With no officers remaining, Beaty took command of the company and led it through a second charge at the Confederate lines. The second attack successfully drove the Confederates from their fortified positions, at the cost of three more men from Company G. By the end of the battle, over fifty percent of the black division had been killed, captured, or wounded. For his actions,

All of Company D’s officers had been killed or wounded in the first charge. So, James H. Bronson, a private and listed as a “musician,” took command of Company D, rallied the men, and led a renewed attack against the Confederate lines. They successfully broke through the abatis and palisades and captured the Confederate positions after hand-to-hand combat with the defenders.

Milton M. Holland Sergeant Major of Company C, took command of Company C, after all the officers had been killed or wounded, and gallantly led it.

Rockbridge artilleryman Moore recalled:

We hurriedly broke camp, as did Gary’s brigade of cavalry camped close by, and scarcely had time to reach high ground and unlimber before we were attacked. The big gaps in our lines, entirely undefended, were soon penetrated, and the contest quickly became one of speed to reach the shorter line of fortifications some five miles nearer to and in sight of Richmond.

Colonel Shurtleff regained consciousness just in time to see his troops “chasing the rebels over a hill a quarter of a mile beyond the works they had captured.”

Arnett’s Company has to fight again at nearby Fort Gilmer;

Division commander Charles Paine, oblivious to the fight the 5th and others had just fought, ordered them to the Confederate-held Fort Gilmer, facing more withering fire. Private Arnett and Sergeant Pinn were among them.

Moore, whose Rockbridge Artillery traveled the five miles from New Market Heights saw what happened from their new position to the right of and close to Fort Gilmer:

The fact that a superb fight was made was fully apparent when we entered the fort an hour later, while the negroes who made the attack were still firing from behind stumps and depressions in the cornfield in front, to which our artillery replied with little effect. The Fort was occupied by about sixty men who, I understood, were Mississippians. The ditch in front was eight or ten feet deep and as many in width. Into it, the negroes leaped, and to scale the embankment on the Fort side climbed on each other’s shoulders, and were instantly shot down as their heads appeared above it.

Sergeant Pinn was shot through the right thorax, rendering his right arm useless for the rest of his life.

Pinn, Beaty, Holland and Bronson (Brunson) were all awarded Congress-approved Congressional Medals of Honor for their bravery that day along with eleven other men of color.

Butler’s report to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton four days after the battle in part read: ‘My colored troops under General Paine…carried intrenchments at the point of a bayonet…It was most gallantly done, with most severe loss. Their praises are in the mouth of every officer in this army. Treated fairly and disciplined, they have fought most heroically.’

https://civilwarscholars.com/uncategorized/d-wilson-arnett-post-references-and-more/