4403 words

https://web.archive.org/web/20180824020548/https://civilwarscholars.com/2014/12/thy-will-20-april-1862-u-s-colored-troops-stop-at-the-lees-home/

.

Chapter 20 – April 5, 1864 – The United States Colored Troops’ Company G of the 19th Regiment Knocks on Henrietta Bedinger Lee’s Door at Bedford, then Overnights in Charlestown.

April 5, 1864 – From a diary of a Shepherdstown resident, who lived there at the time:

Something new! Three hundred black soldiers came to town and some are quartered in the Jim Lane Towner storeroom and they are in the command of Colonel Perkins. Others with white skin and black hearts took Dan Rentch’s parlor for headquarters. These negroes were hailed with much joy by some of our loyal citizens and some five or six negro soldiers were invited to breakfast with her by Mrs. C__ (A leading Unionist family in town were the Colberts.-JS)

April 7, 1864 – The diarist continues: The black yankees left hurriedly for Harper’s Ferry, for the river was up and they could not get back into Maryland, and rebels were reported to be coming.

April 9, 1864 – The diarist continues: Twenty-six negro soldiers and a white officer came to town and quartered in Mohler’s store (Possibly “Moulder’s” Store at southwest corner of German and King Streets. – JS)

April 12, 1864 – Diarist continues: Twenty-four black yankees and a white officer passed through, going to Martinsburg.

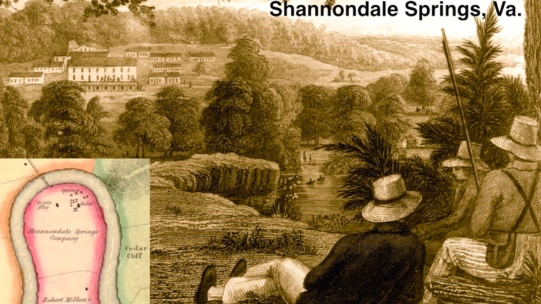

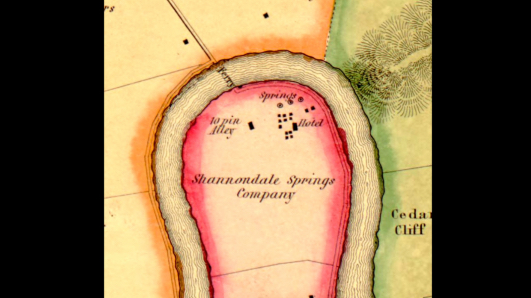

Then twenty-year-old Netta Lee was living at Bedford outside Shepherdstown at that time with her mother Henrietta, her younger brother, Harry, and enslaved African-Americans: a worker named Nace; father and daughter, Tom and Keziah Beall; Peggy Washington and her three grand-sons – Thompson, William and George, and her grand-daughter Virginia, also called “Jinny.” Edmund Lee, Sr., Netta’s father, was away; son/brother Edwin Grey was in the Confederate army and Edmund, another brother, had enlisted the year before in 1863 when he became old enough to serve.

The United States Colored Troops organization was created by presidential order in May, 1863. In letters of Henrietta Lee and Tippie Boteler, they write that most able-bodied, enslaved African Americans left the County for good as of May, 1863, posing challenges in household upkeep and crop production for them. – (1).

Netta Lee wrote:

The months sped by and we were in the second (should be: “third”-JS) year of this terrible war. All of our men, including Edmund, the next to the youngest brother, had gone to join the army, leaving Harry, a boy of about thirteen, as our protector, and seized every opportunity to come home, or as near home as possible when our troops were in the Valley. Mother and I were seated on the portico one bright morning, playing a game of chess. So intent were we upon our play that not one word had been spoken, save an occasional monosyllable: “Check!” when Harry came running up the gravel walk toward us. The boy’s eyes seemed black with indignation, his face flushed with anger.

“What is it, Harry?” we both exclaimed in a breath. “What has happened – another battle? Tell us quickly!”

“. . . The white yankees, who were quartered here at the river to picket the town have been removed, and Heaven knows they were bad enough, but now a negro regiment has replaced them and will be here tonight!”

Our Mother’s face grew pale. She arose and placed her hands on Harry’s and my shoulders as we stood beside her, saying: “Through Captain Cole’s reign, our Father in Heaven has guarded us, my children: I do not believe the negroes can be worse than Captain Cole’s men were. . .”

(Netta to Harry): “A regiment of them, did you say, Harry?” I asked. “Yes, And we hear they are going to draft all the able-bodied men under forty-five years.”

“Have they white or negro officers?”

“Oh, white officers, all of them. And what is worse, I hear they are going to camp out of town in this lot of ours next to the meadow.”

“Oh, that is too outrageous,” exclaimed Mother.

Just at this moment was seen approaching from one of the servant’s cottages, a stately elderly negro woman with a tall white turban on her gray head and a red kerchief crossed over her chest. She was walking briskly and talking to herself.

“There comes Aunt Peggy (Washington),” I said. “Mother, she must have heard the bad news.”

“Yes,” continued Harry, ”for George was in town with me.”

Peggy Washington said: “Lord Miss Netta, is that so about the soldiers coming to this town and drafting everybody they can?”

Netta: “Yes, Peggy. Harry says they really are to be here tonight. I was just going to send for you and tell you to fix up something to eat for the boys, Bill, Thompson and George, and send them out to the farm (Oak Hill on the Kearneysville Pike) before sun up tomorrow morning. They must stay there all day tomorrow. Be sure they start very early.”

Peggy: “Yes, that’s so. I’ll get them off in time. The nasty trash. They aren’t going to get my grandsons, all the children I’ve got left, and make them fight against the ones they they played with all their lives.”

Netta: “Well, you see, Peggy, we don’t know what these new men will do; but the boys will be safe at Oak Hill.”

Peggy: “Yes, that’s so. I’ll get them off in time.”

Henrietta: They must hide during the day and return home at night for food; and none of them must go to town tonight,” said Mother.

“No m’am! They won’t want to go to town tonight!”

Netta Lee wrote:

Sure enough, it was well. Peggy got her boys off early to Oak Hill for the report was true and next day negro troops encamped in our fields; and Harry called to me: “Just come and see how they are shooting down all the hogs in sight.” And Mother added: “I am glad I made the boys lock up all the sheep, which are quieter animals than these hogs, though, no doubt they will soon follow, except (they will) love hog meat better than anything unless it is chickens.”

. . . (As he looked through a field-glass, his mother asked Harry): “What are they doing now, Harry?” “A squad of them seems to be coming this way.”

Mother hastily turned to the door, saying: “Come, let us go in. I don’t want them to see us looking at them.”

We went into the library, where I busied myself buckling the belt of my little six-shooter around my waist, taking care that its bright silver mounting could be seen. On a table near her was Mother’s larger one, similarly mounted. She was just about to lay her hands upon it when Jinny, her old Granny’s (Peggy Washington) favorite, came bursting into the room . . .

“Oh Mistiss, Granny says come down in the kitchen quick, please ma’am. Those soldiers are down there.”

Hastily Mother placed her pistol in her pocket, keeping her hand upon it. Then all of us started to the basement kitchen. There we found a party of six or seven stalwart negro soldiers insolent and swaggering. None however were actually inside the door; but two were on the threshold and swearing at Peggy, who had thus far kept them at bay with a large butcher knife and her tongue – the latter weapon being the sharper of the two. She was arguing manfully with them, saying: “I’m not afraid of yankees!”

“What does all this mean?” asked Mother, who met the two of them as they succeeded in pushing past Peggy, starting to come up the basement stairs. “What are you here for; who sent you?” asked Mother.

“We were sent here for your three young colored men,” the man replied. “We’re gathering up recruits.” (NOTE: William, Thompson and George were all draftable age in their late teens. – JS)

Peggy broke in with: “I told them, Miss Netta, that there weren’t any men here. Then they told me they were going to search my room and the house and see if I didn’t hide them.”

“Well,” said mother, “. . . and tell your officers there are only young boys. Go now, and don’t dare to come to this house and try to steal our young servants.”

“We’re only doing what we’ve been sent and ordered to do. We have to obey orders or get shot,” replied the spokesman.

“Yes,” said mother, “We heard before you came here that one of your officers shot a man for refusing to black his boots. Is that true?”

“Yes, ma’m, he did that very thing. ’Twas our Captain.” (NOTE: An in-depth review of service records shows no accidental death of men in Rickard’s company G, the company in Shepherdstown. In letters and speeches after the war, Rickard conveyed an attitude of an abolitionist on a mission when speaking of his role as a USCT officer. One might see this account as Netta Lee and Henrietta B. Lee projecting their perception of a cruel slaveholder in Virginia on the persona of a USCT officer.-JS)

“Well, now you obey my orders and go to your officers and tell them what I have told you: “There are no men here; and also tell them that Southern women know how to shoot as well as their men do. Go!” said Mother. (Netta wrote): I was not slow to let them see the hilt of my pistol, and Mother kept her hand on hers. Harry, too kept around, with his military belt and Confederate buckle, showing that he also might be carrying arms, as he was, for in that belt was hidden a sharp, two-edged dagger.

Only for a short time were the negro soldiers encamped near Bedford; they seemed to have been sent here to gather up negro recruits, and having accomplished their purpose, were soon replaced by a company of white men under the command of Captain Teeters.

George, Thompson, and Bill had kept well out of sight of the negro soldiers and Harry had kept his chickens in close confinement, too, up to the day of their departure. So the day the negroes marched across the Potomac, Harry came in saying: “Mother, I think I may as well let all those fowl out.” Those two game roosters have fought every day since I penned them in the chicken house and have nearly killed each other. Bill and I have named them Abe and Jeff.

“Well,” said Mother, “put one of them in the cellar and tell Peggy she can kill him tomorrow.” “All right!” says Harry, “I will imprison Abe. – (2).

There are records suggesting two of Peggy Washington’s three grandsons did, indeed, wind up in uniform with the U.S. Colored Troops.

Service records indicate enlistments into the U.S. Colored Troops by two men with the names of 56-year old (1864) Peggy Washington’s grandsons, both enlistees also born in Jefferson County. It should be noted that the Lees refer to enlistment men in their households as “boys,” creating a wrong impression of their age.

There is a record of a Jefferson County-born African American named William H. Washington, who was born in 1834 in Jefferson County, and who enlisted in 1864 in the 32nd USCT Infantry at Chambersburg, PA. He was at least the same generation of the Lee’s butler named “Bill.”

Service Records also show a Jefferson County-born African-American named George Washington, enlisting September 12, 1864 at Harper’s Ferry into the 37th U.S. Colored Troops in Company K. He deserted October 1, 1864.

There are no service records by the name of Ms. Washington’s third grandson, Thompson, but a 35-year old African-American by that name appears in the 1870 Census in the adjacent Loudoun County, Va. – (3).

Robert Summers, curator and webmaster for 19usct.com website gives details of men who were with Co. G of the 19th USCT at the time of the visit to the County in April, 1864.

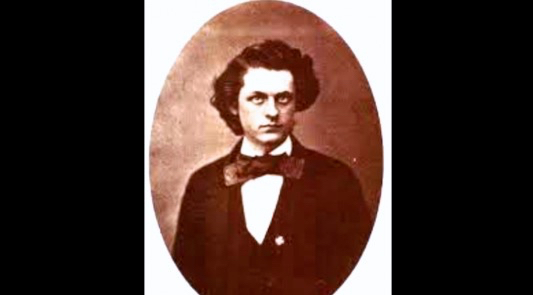

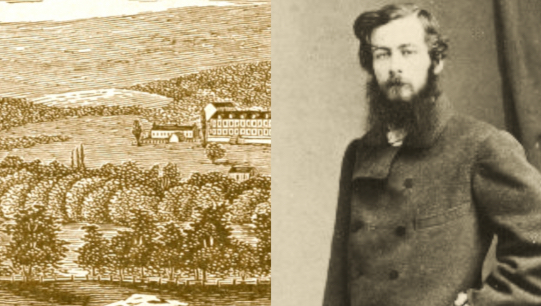

Summers gives a brief biography of their white commander:

25-year-old James H. Rickard, from Woonsocket, Rhode Island, joined the 18th Connecticut Volunteers on August 7, 1862, fought at Winchester, Virginia on June 13-14-15, 1863, received an appointment as Captain in the 19th Regiment, U.S. Colored Troops on March 12, 1864, and joined the regiment at Camp Birney, Baltimore, Maryland, on March 31, 1864. He was discharged from the Union Army by reason of physical disability (malaria) on March 26, 1866. After the Civil War, Rickard lived in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, working as a merchant. Captain Rickard died on May 5, 1914 and is buried in Union Cemetery, North Smithfield, Rhode Island.

Summers provides the text of an 1894 lecture by Captain Rickard before the Rhode Island Soldiers and Sailors Historical Society.

. . . at least 186,097 black soldiers, mostly ex-slaves, fought for the United States government, and that 36,847 of this number (nearly twenty percent) were either killed or died in United States hospitals. That they took part in 449 engagements, and for soldierly bearing and heroism challenged comparison with their more fortunate white comrades.

Soon after joining my regiment, Lieutenant-Colonel Perkins, in command, obtained permission to take the regiment up the Shenandoah Valley recruiting. Arrived at Harper’s Ferry, with much difficulty we obtained a four-mule baggage wagon and started up the Valley for Winchester.

Col. Perkins was a peculiar individual, and seemed bent on making some kind of a demonstration with his regiment of colored men. When about halfway from Berryville to Winchester our advance guard were fired upon, and returned the fire; for a moment some confusion prevailed, as it was expected we were intercepted by a rebel force. After forming a line to the left of the road in a rocky piece of woods, an officer was sent forward to ascertain the cause of the firing. It was found that a company of our scouts, dressed in gray, had opened fire on our men to see how they would stand. Our men then returned the fire and did not flinch. One colored man was struck on the forehead by a minie ball, and a piece of his skull as large as a silver half dollar knocked out, but it did not knock him down. He was assisted by his comrades, and when the wagon came up he was put in, and when after several days we returned, he was sent to the hospital, and came back healed, and did good service afterward. Our expedition continued to Winchester, where the Colonel intended to pass the night, but having served in this valley previously and knowing the danger of remaining there, I prevailed upon him to move on to Bunker Hill, where we might be within supporting distance from Martinsburg should we be attacked; and I had information that a superior mounted force of the enemy were present.

Rickard provides the larger context in which Company G came to Shepherdstown:

On the way to Bunker Hill that night we met about eight hundred of our cavalry passing up the valley from Martinsburg; they were attacked the next morning and entirely routed, proving the wisdom of my insisting that we move on and not stop over night there with our small force of less than 750 men, untrained and untried.

From Martinsburg we passed over into Maryland to Shepherdstown and back to Harper’s Ferry. I was then ordered to proceed with my company to Charlestown with three days rations, and “recruit vigorously.” My men had only five rounds of ammunition. I asked for 40 and was refused. I went under protest, as I knew that with less than one hundred colored men, ten miles away from any assistance, with only five rounds of ammunition, it was a foolhardy adventure, as Mosby with his guerrillas was scouring that country continually, and there were probably more Confederate soldiers in Charlestown at that time, well-armed, than my company numbered. It was a cold stormy night, about the first of April, when I arrived there. I quartered my men in a church, situated on the south of a square, the country to the south of the church being open toward a knoll where John Brown was hung. After seeing that the men were comfortably cared for, I found quarters near by in a cottage. The woman, whose husband was in the rebel army, was violently loyal to the Confederate cause. After much bantering and my offer to pay, I got a good supper, and a feather bed on the floor in front of a good fire. I was very anxious, and placed four or five pickets out and a sentinel in front of my door, with orders to report to me immediately any noise like the tramp of cavalry.

I was just getting into a doze, between one and two o’clock. The sentinel knocked on the door and said, “I hear cavalry.” Having removed only my sword and boots, I was outside in an instant. I could hear the heavy tramp of a large force of horsemen apparently entering the place from the northwest. I had the men quietly aroused, and knapsacks packed without lights, and held a hasty consultation with my lieutenant (Raymore) and decided that “discretion was the better part of valor.” It was raining and intensely dark. I moved down the macadamized pike towards Harper’s Ferry, where if attacked I might be within reach of assistance if necessary. We continued our march about four miles, when we reached a cavalry vidette, thrown out from Harper’s Ferry. I ascertained from him that a force of cavalry of our own troops had gone up the valley on a reconnoitering expedition, and on account of the muddy condition of the roads had gone up the road to the north, and entered the place from the northwest. Knowing now that there were troops between me and the enemy I was relieved of my anxiety, retraced my steps, and went back to the same quarters and slept soundly. – (4).

According to Summers’ research, these are some of the men who were active in Co. G. of the 19th U.S. Colored Troop in April, 1865, at the time the company participated in recruiting in Jefferson County and in Shepherdstown:

Alexander, James

39-year-old James Alexander enlisted in Frederick, Maryland on December 31, 1863. Older men were prized for their maturity, and Alexander was immediately promoted to 1st Sergeant of Company G. He served with the regiment throughout the war, and afterwards in Texas. He was mustered out with the rest of the regiment on January 15, 1867 in Brownsville, Texas.

Banks, Jenkins

30-year-old Jenkins Banks enlisted in Dorcester, Maryland on January 6, 1864, and mustered into the 19th Regiment on January 10, 1864 at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland. Private Banks was taken sick on June 11, 1865 while the regiment was en route to Texas after the war, and taken to the New Orleans quarantine hospital. After recuperating, he joined the regiment in Texas. Unfortunately, Banks contracted dysentery while in Texas, and died of that disease on September 7, 1865 at Galveston, Texas. Other records show the date of death as July 22, 1865. Private Banks was originally buried in Galveston, Texas, but his remains were later transferred to the Alexandria National Cemetery in Pineville, Louisiana.

Bond, John

30-year-old John Bond enlisted on January 7, 1864 in St. Mary’s County, Maryland, and mustered into 19th USCT on January 10, 1864 at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland. In the early spring of 1864 Private Bond served as part of a Union Army recruiting party that recruited slaves from the farms and plantations He died of pneumonia five months later, on August 21, 1864, at the City Point, Virginia, Army Hospital. The hospital failed to report Bond’s death to the regiment, which carried him as sick for the balance of the war, and as a deserter after the war. Finally, in 1883, when processing his widow’s pension application, the Army discovered and corrected its mistake, removed the charge of desertion, and corrected Bond’s records to show that he had died in the line of duty.

Briscoe, James

18-year-old James Briscoe was a slave of Edward Wilkens of Kent County, Maryland when he enlisted on January 1, 1864. He mustered into the 19th Regiment USCT on January 10, 1864 at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland. Wilkens was awarded $300 compensation for James Briscoe’s enlistment. Private Briscoe served with his regiment throughout the war, and afterwards in Texas. He died in the Post Hospital at Brownsville, Texas on July 31, 1865 of chronic diarrhea. He was buried in National Cemetery at Fort Brown in Brownsville, Texas. In 1911, National Cemetery was closed and his remains were moved to Alexandria National Cemetery in Pineville, Louisiana.

Butler, John

23-year-old John F. Butler enlisted on January 7, 1864 in St. Mary’s County, Maryland, and mustered into the 19th Regiment USCT on January 10, 1864 at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland. Corporal Butler was wounded by a minie ball at Petersburg, Virginia on September 30, 1864 and sent to the Summit House Army General Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania where he died of erysipelas on March 20, 1865. Mr. Butler was survived by his wife Sylvia Butler.

Chambers, Samuel

20-year-old Samuel Chambers enlisted in Queen Anne’s County, Maryland on January 2, 1864, and mustered into the 19th Regiment on January 10, 1864 at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland. Private Chambers died of pneumonia on August 1, 1864 at the Army hospital in City Point, Virginia.

Cooper, Lewis

30-year-old Lewis Cooper, a married man, enlisted in Cecil County, Maryland on January 2, 1864 and mustered into the 19th Regiment on January 10, 1864 at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland. Private Cooper fell ill and was sent to the L’Ouverture Army Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia on October 14, 1864. He died there on November 30, 1864. The cause of death was listed as Ascites. He was buried at Alexandria’s Freedmen’s Cemetery, but subsequently interred at Soldiers Cemetery, now known as Alexandria National Cemetery.

Demby, Emery

26-year-old Emery Demby was married to Sarah M. Demby when he enlisted on January 6, 1864 in Talbot County, Maryland. He mustered into 19th USCT on January 10, 1864. Demby was with the regiment throughout the war, and in Texas afterwards. He died of cholera on November 20, 1866 in Brownsville, Texas.

Hackett, Thomas

23-year-old Thomas Hackett enlisted on January 7, 1864 in Dorcester County, Maryland, and mustered into the 19th Regiment, U.S. Colored Troops on January 10, 1864 at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland. Private Hackett served with the regiment throughout the war, and afterwards in Texas. He became ill while in Texas and died of bone fever at the Post Hospital in Brownsville, Texas on August 10, 1865. He was buried in National Cemetery at Fort Brown in Brownsville, Texas. In 1911, National Cemetery was closed and his remains were moved to Alexandria National Cemetery in Pineville, Louisiana.

King, Thomas

18-year-old Thomas King was a slave of Henry King in Somerset County, Maryland when he enlisted there on January 6, 1864. He mustered into the 19th Regiment USCT on January 10, 1864 at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland. Private King fell ill with inflammation of the lungs and was sent to L’Ouverture Army Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia on April 26, 1864. He was released from the hospital on June 6, 1864 and returned to his regiment outside Petersburg, Virginia. Private King was killed in action at the battle of Cemetery Hill near Petersburg on July 30, 1864.

Kinnard, Charles

24-year-old Charles Kinnard enlisted on January 7, 1864 in Dorchester County, Maryland. He mustered into the 19th Regiment, U.S. Colored Troops on January 10, 1864 at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland. Private Kinnard served with the regiment for the rest of the war, and went with the regiment to Texas after the war. He fell sick on February 25, 1865 and died in the Army hospital in Brownsville, Texas on November 12, 1865 from chronic diarrhea.

Lindsey, Stephen

21-year-old Stephen Lindsey enlisted on January 2, 1864 in Kent County, Maryland, and mustered into the 19th Regiment USCT on January 10, 1864. Private Lindsey was killed in action at the battle of Cemetery Hill outside Petersburg, Virginia on July 30, 1864.

Matthews, Judson

Matthews enlisted on January 5, 1864 and mustered into the 19th Regiment, U.S. Colored Troops as a Sergeant on January 10, 1864 at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland. While the regiment was stationed in Texas, Sergeant Matthews was sick most of the time in the post hospital at Brownsville, Texas, suffering from pains in his stomach, legs, feet, and head. The common diagnosis for this illness at the time was bone fever. He was still sick when he mustered out of the Army on January 15, 1867 at Brownsville.

Murray, Henry

30-year-old Henry Murray enlisted on January 1, 1864 in Kent, Maryland, and mustered into the 19th USCT on January 10, 1864 at Camp Stanton, Benedict, Maryland. Murray was judged to have valuable leadership skills, as he was soon promoted to Corporal. Corporal Murray died during the regiment’s march to the battlefield at Petersburg, Virginia.

Captain Rickard wrote his widow:

To all whom it may concern

Camp in the field near Petersburg VA

June 19, 1864

Madam:

I have to announce to you the sad intelligence that your husband “Henry Murray,” a Corporal in my Company died this morning. He has not been well for some time & yesterday he accidentally fell into a small stream which we crossed on a march. He was brought along in an ambulance & died this morning. He was a good & faithful soldier. I regret his loss & sympathize with you in your bereavement.

Respectfully Yours,

J.H. Rickard

Capt., 19th U.S.C. Troops

Comd’g Co. G

It should also be noted that thirty-year-old free African-American William Spellman in Charlestown enlisted in the 19th USCT regiment in Frederick, MD, May 24th that same year, fought at the “Mine” and Petersburg and mustered out January 15, 1867 in Brownsville, Texas. – (5).

Overall, Service Records indicate that as many as 158 African-American men who were born within Jefferson County served in the United States Army with a rank of private up to major, which was the rank of Martin R. Delany, who was personally recommended by President Abraham Lincoln for appointment and promotion to major following an interview at the White House in early February, 1865.

Two other enlisting African—Americans from Jefferson County who may have also worked for the Botelers and or Pendletons were William Bunkins who enlisted July 13, 1864 into the 23rd USCT Infantry Regiment when he was about 24-years-old, and Randolph Thornton, who enlisted into the 3rd USCT Infantry Regiment on July 3rd, 1863, when he was twenty-three-years old.

William, who served as a hospital steward at Camp Casey in Virginia throughout the war and lived in Jefferson County in 1880, is a likely relation to a Wilson or Nelson Bunkins, who was born in 1841 and was the husband of Margaret Bunkins, a servant, along with their daughter Fanny, for the Botelers on the fateful day in July, 1864 when Fountain Rock burned.

Randolph Thornton, who mustered out in Jacksonville, Florida in 1865 and was living with his family in Charlestown in 1880, may have been a relation to the only African-American Thornton family in the County in the 1850s, a large enslaved family that worked for both the Pendletons and the Botelers, and some of whom emigrated to Liberia in 1855. – (6).

References/Image Credits;

Chapter 20: The United States Colored Troops’ Company G of the 19th Regiment Knocks on Henrietta Bedinger Lee’s Door at Bedford.

1. Jefferson County Historical Society Magazine, Volume LXII. December 1996.

Fragments of a Diary of Shepherdstown – Events During the War 1861-5.

2. Netta Lee Diary, pp. 8-11.

3. Service Records, United States Colored Troops. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

4. Robert Summers – Curator/Webmaster for http://19usct.com

5. Ibid.

6. Service Records of the United States Colored Troops.

NEXT: Chapter 21. https://civilwarscholars.com/shepherdstown/thy-will-be-done-21-tom-beall-kizzie-and-her-secret-society-by-jim-surkamp/